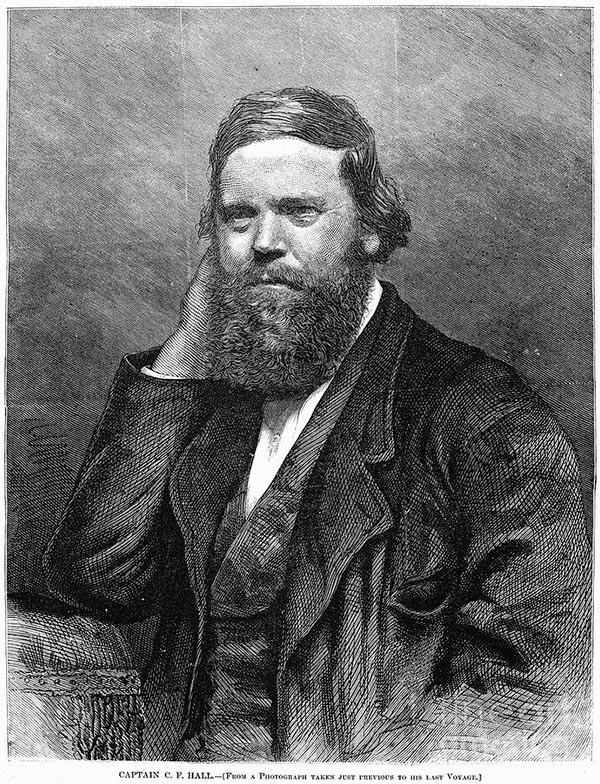

Charles Francis Hall (1821 - November 8, 1871) was an important American born Arctic explorer who made his most important explorations in the vicinity of Baffin Island and King William Island between 1860 and 1871. Hall was born in Rochester, New Hampshire where he apprenticed to a local blacksmith. Apparently a life at the anvil was not his thing because he seems to have abandoned that calling. Several years later he appeared in Cincinnati, Ohio where he founded and published a local newspaper, The Cincinnati Occasional. Around 1857, Hall became fascinated with Arctic exploration and obsessed with the idea that members of English nobleman Sir John Franklin's missing expedition were still be alive and living with indigenous Inuit communities. It was not until 1860 that Hall was able to finally make it to the Arctic onboard the whaler George Henry. He was dropped off on Baffin Island where he befriended a local Inuit couple, Ebierbing (called "Joe") and his wife Tookoolito (called "Hannah"). This couple, who would remain with him for the remainder of his Arctic explorations, told Hall of the ruins of Martin Frobisher's 16th century mining venture at nearby Frobisher Bay. At the time Frobisher Bay was assumed by westerner cartographers to be a Strait between Baffin Island and another unknown landmass. Hall explored the old mining camp as well as the "Frobisher's Strait" and for the first time on record correctly identified it as a "Bay". While studying the area, Hall also found evidence that he claimed pointed to the survival of several members of Sir John Franklin's expedition on King William Island, to the west. Armed with his evidence and the Inuit couple "Joe" and "Hannah", Hall returned to the United States to raise money for a second expedition. Coming home to a nation embroiled in a terrible Civil War, Hall had a hard time raising funds. Nonetheless, just two years later in 1864, Hall embarked on a second expedition to King William Island in search of Franklin and his crew. Several years later Hall did in fact discover what he considered to be the remains of the expedition - bones, charcoal, and some basic tools. He was horrified that the expedition of 40 or so had been left to starve by local Inuit peoples, though never seemed to realize that the local population could barely feed itself through the harsh Arctic winters. Returning to the U.S., Hall determined to make a future for himself in the hearty field of Arctic Exploration. He petitioned Washington for funds and was successfully granted 50,000 USD to lead a ship, a distinguished crew, and three scientists to the Arctic. The Polaris Expedition, as it was known, had an auspicious start though Hall almost instantly fell out with the expedition's scientists, with whom he fought over leadership issues. The expedition reached Greenland in September of 1871 where it settled in to wait out the coldest winter months. Two months later, in early November, Hall drank a cup of coffee and suddenly fell ill. He died days later while accusing the ship's physician and leader of the three scientists, Dr. Bessels, of poising him. He was buried in Greenland on November 8 of 1871. The official investigation determined that Hall died of apoplexy. About one hundred years later in 1968, Hall's biographer Dartmouth professor Chauncey C. Loomis, made a trip to Greenland to exhume the body. The Arctic cold left Hall in an extraordinary state of preservation and tests were able to conclusively prove that Hall did in fact die of Arsenic poisoning.