This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1925 Cyanotype Map of the NWK Mills Shanghai - beginning of May Thirtieth Movement

ShanghaiMillsBlueprint-unknown-1925$3,750.00

Title

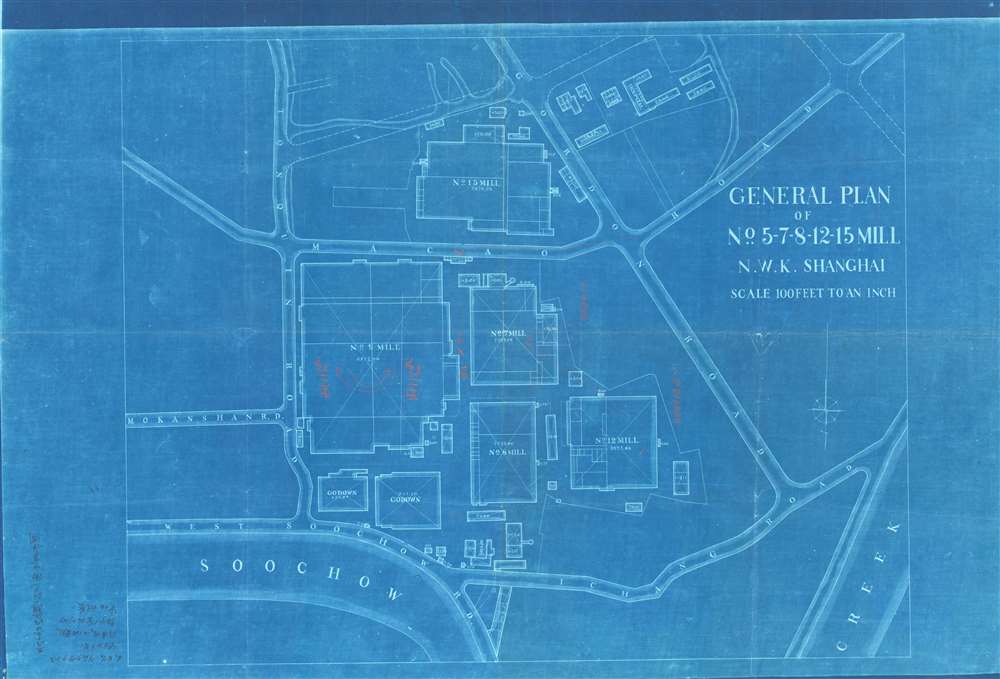

General Plan of No.n 5-7-8-12-15 Mill N.W.K. Shanghai.

1925 (dated) 20.5 x 30.5 in (52.07 x 77.47 cm) 1 : 12000

1925 (dated) 20.5 x 30.5 in (52.07 x 77.47 cm) 1 : 12000

Description

Recording the beginnings of the May Thirtieth Movement, a pivotal moment in the rise of labor unions and communism, as well as the end of the Unequal Treaties, in pre-war China, this is a striking 1925 cyanotype map of the Nagai Wata Kaisha Cotton Mills (NWK) in Shanghai, just south of Suzhou Creek (or Soochow Creek). Dating to May of 1925, the map focuses on those NWK Mills attached to a series of historic labor strikes against Japanese operated textile mills operating in Shanghai. In specific, manuscript annotations refer to the May 15th event, an armed engagement between workers and Japanese management in which a young Chinese worker, Ku Cheng-hung (顧正紅), was mortally injured. The partially successful strikes led to only marginally improved labor conditions, but can be considered to represent the first stirrings of Communism in Shanghai. The fact that this map is a cyanotype underscores its role as a highly ephemeral production, likely produced to deal with the violence of the strikes. Given the limitations of the cyanotype technique, only about 10 -15 of these were likely made - representing an ephemeral but fundamental moment in Shanghai history.

The May 15th Ku Cheng-hung Incident

Japanese manuscript text on the map identifies this map as detailing the armed conflict that occurred in these mills on May 15th. Here is what it illustrates,On 4 May (1925) workers in Naigai Wata Kaisha no. 8 mill struck for a wage increase, but following negotiations, work was resumed on the 7th. Only a few hours had elapsed when the dispute again erupted, and the strike recommenced Factories nos. 3 and 5 immediately struck in solidarity, and they were soon joined by workers from the Tung Hsing and Japan-China silk companies. On the 14th, the strike spread to NWK no. 12 factory. On the 15th, no. 7 mill was closed down by the management, on the grounds that it could not function for lack of material from the other mills. The workers who arrived for night shift did not accept this, and forced their way past a party of Sikh police and Japanese foremen. They armed themselves with sticks, iron bars, and other weapons, and surrounded a group of Japanese, whom they greatly outnumbered. A young worker … Ku Cheng-hung, led a rush against them, whereupon the Japanese opened fire with pistols, injuring some ten Chinese, including Ku, who died of his injuries on 17 May. Four Japanese were also seriously wounded in the clash. Most of the strikers then withdrew, but some, who sought refuge in Mill no. 5 [here heavily annotated I red manuscript], were locked in by the Japanese, whereupon they wrecked the machinery, which resulted in further discontinuation of operations. (Riby, Richard W., The May Thirtieth Movement: Events and Themes, page 29.)This event led to further unrest and the involvement of the Shanghai Municipal Council Police - where were generally pro-Japanese and justly distrusted by the Chinese workers. Events culminated on May 30th, the Shanghai Massacre, discussed later, in which British Shanghai Municipal Police officers opened fire on Chinese protesters.Background on Labor Unions in Shanghai and the 1925 Strikes

Nagai Wata Kaisha Cotton Spinning and Weaving Company, commonly known as NWK Mills, was a Shanghai-based Japanese-owned complex of cotton mills active in the pre-war period. The British missionary J. B. Taylor, writing in the 1920s, says of NWK,The Japanese in their recent industrial expansion in China have apparently resolved to be second to none, and in the comparatively new Nagai Wata Kaisha mills, for instance, they have set a high standard.We can only assume he was referring to modernization, not labor standards, which were notorious for their inhuman brutality. Describing the conditions, the NWK strike committee published the following appeal for public support,Fellow countrymen! Japanese Imperialism in the Chinese people's greatest enemy. We can never forget the various incidents of cruelty against our Chinese fellow-countrymen … In the first half of this year a whole number of Japanese mills arrested workers' leaders and subjected them to brutal torture, including the electrocution of Hao Huoqing; and apart from these leaders, it has threatened ordinary workers with the sack. Everybody knows that the plunder and oppression of Chinese workers in Japanese mill sis a hundred times worse than in other factories. (Smith, Steve, A Road Is Made: Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927)In 1925, NWK became the center for mass strikes throughout the Japanese operated cotton mills of Shanghai. In February the management of NWK Mills dismissed some 40 Chinese employees for 'disobedience.' By February 10th, dissatisfaction over the firings evolved into a major labor strike which, by February 20, had expanded to include more than 20 mills and 30,000 Chinese strikers. Within days these numbers had further expanded to more than 140,000 Chinese mill workers. Within NWK, the strike initially focused on the mill cluster shown on this map, the Mills 4, 5, 7, 8 and 12, with 15 and 13 joining on the 25th. While the mills quickly negotiated a settlement with the workers that included the establishment of a labor union, pay raises, and other concessions, these concessions were insufficient to stifle the unrest, leading to further strikes in May (as illustrated on this map), and the first stirrings of communism in China. Note the communistic flavor this subsequent publication,Japanese capitalists are truly hateful. They treat us Chinese workers like slaves of a conquered nation, beating and cursing us as whenever they like, making deductions from our wages, giving us the sack. The time has come when we can stand it no longer, and so we have all risen up to go on strike (yaoban). … All capitalists think only of making money and the stubbornly exploit us; but foreign capitalists, relying on the might of their governments, oppose us Chinese workers even more. We, Chinese workers and compatriots, must unite on a grand scale to resist them. Workers of all trades, our strength lies in the fact that we are a million people of one mind! (Smith, Steve, A Road Is Made: Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927)While some consider the strike a victory, in truth it failed to achieve major reform. The mills did make some concessions to the strike committee, but ultimately, these were minor compared to the demands. Nonetheless, the events, in aggregate known as the May Thirtieth Movement, did lead to the rise of labor unions in the mills and increased anti-Japanese sentiment in China. The May Thirtieth Movement may have turned into nationwide labor solidarity unions, like emerged in Europe and the United States, but instead, the 1931 Mukden Incident and the Japanese invasion of China during World War II, led to Mao Zedong's more militant Communist Revolution.May Thirtieth Movement

These event were part of what is generally known as the May Thirtieth Movement (五卅运动), a major labor and anti-imperialist movement focused on Shanghai during the middle-period of the Republic of China era. The movement in generally considered to have started with the Shanghai Massacre, in which British Shanghai Municipal Police opened fire on Chinese protesters (killing 4, mortally wounding 5, and hospitalizing 14), but in fact the lead up is more complicated and generally associated with resentment against the Japanese industrialist - as the events on this map suggest. The May 30th massacre galvanized China, and strikes and boycotts, coupled with often violent demonstrations, spread across the country, bringing foreign economic interests to a standstill. The shootings reoriented Chinese ire from the Japanese to the British. Events became particularly confrontational in Hong Kong during the Canton-Hong Kong Strike (June 1925 - October 1926). These events fostered further unrest throughout China and were capitalized on by Chinese warlords to further their own political agendas. Things finally died down when Kuomintang leader Chiang Kai-shek overcame his many rivals and consolidated the Chinese federal government. The Kuomintang's support for the movement, and its Northern Expedition of 1926 - 1927, eventually led to reforms in the governance of the International Settlement's Shanghai Municipal Council and is regarded as the beginning of the end of the Unequal Treaties.Cyanotype: Why so Blue?

Cyanotype is a photo-reprographic technique developed in 1842 by the British astronomer John Herschel (1792 - 1871). Sometimes called a 'sunprint', the technique employs a solution of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide, which painted on white paper or cloth, reacts when exposed to sunlight to dye the object a brilliant blue. Areas blocked from ultraviolet exposure remain undyed and white. Herschel developed the technique to reproduce his astronomical notes, but others quickly realized that any object capable of blocking light could be used to quickly and easily create a cyanotype image. By the late 19th century the process became popular with designers, military, architects, and engineers (blueprints), who used the cheap an effective technique to quickly and exactly reproduce images in the field. Cyanotyping is limited in that only a single copy can be made at one time, so it was only practical for short-term field work. It is also of note that cyanotypes remain extremely reactive to light and, over time, fade or degrade, making them extremely ephemeral. The process fell out of fashion in most places by the 1920s, but remains in use in some parts of the world, such as India and Nepal, to this day.Census and Publication History

This is the only surviving example of this map. The cyanotype method of graphic reproduction is limited to very low print runs, typically less than 20, and due to the photo-sensitive nature of the medium, tends to have a very limited survival rate. The manuscript annotations firmly date the item to May 1925.

Condition

Very good. Cyanotype.

References

Rumsey 6850.001. OCLC 8795027.