This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

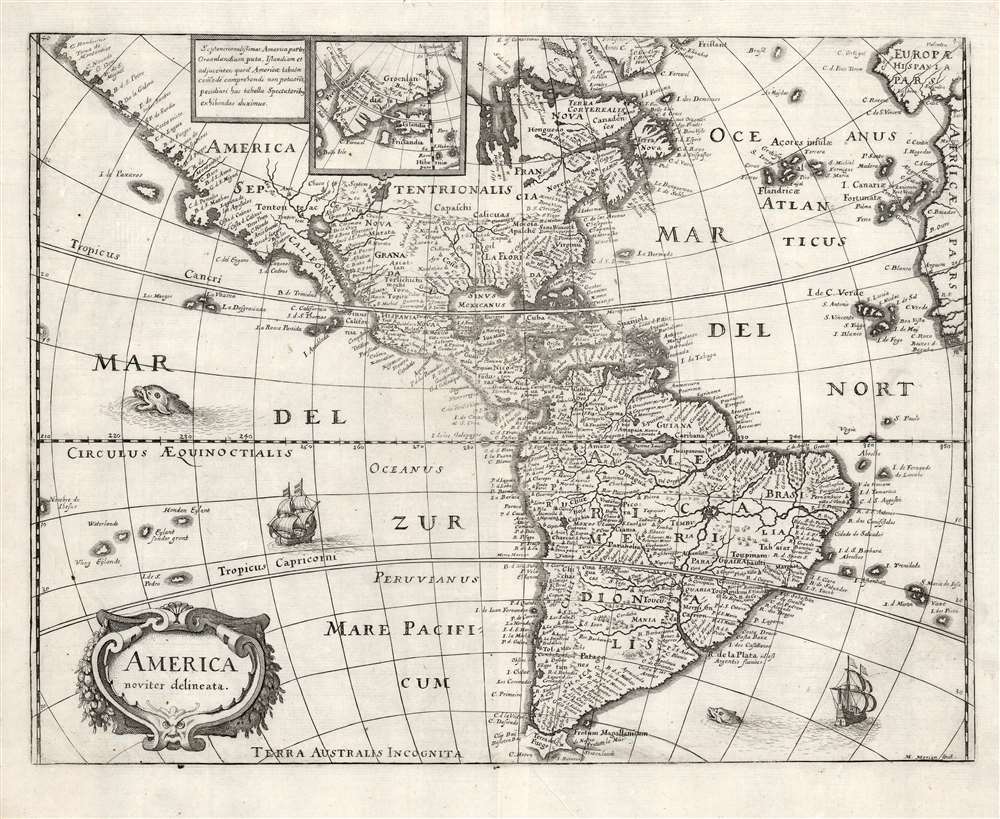

1646 Merian Map of America, after Blaeu

America-merian-1646

Title

1646 (undated) 11 x 14.25 in (27.94 x 36.195 cm) 1 : 50000000

Description

Sources

Merian's source for the present map was not, as Burden suggests, Jodocus Hondius Jr.'s 1618 map of the same title, but Blaeu's Americae Nova Tabula, whose detail here is presented with a high degree of faithfulness (though dispensing with Blaeu's decorative borders). It is an interesting choice but appears to be consistent with Merian's decision to copy Blaeu's world map in this volume.Tierra del Fuego

Hondius' 1618 map of the Americas bears many similarities to the Blaeu; one area of divergence is in the depiction of Tierra del Fuego. The first issue of Blaeu's map in 1617 was notable for its very primitive depiction of the island: Blaeu had been barred by the Dutch East India Company from including the discoveries of Le Maire and Schouten. When confronted with the reality that other mapmakers were not so unfairly circumscribed, the VOC relented and permitted Blaeu to amend his map in 1618. Blaeu's map lacks Hondius' Draex Eylanden but includes the Pacific Islands reported by Le Maire and Schouten, which do not appear on the Hondius. In the Atlantic, Blaeu's map shows the I. Dos Picos at the Tropic of Capricorn. The presence of these islands on the Merian attests to a relationship to the Blaeu rather than the Hondius.Greenland and Iceland

Like the corresponding Blaeu and the Hondius maps, Merian's America includes an inset map focusing on Greenland, Iceland and Frisland, and the Davis Strait. The inset in the Hondius is oriented to the east; the inset here is oriented to the north, corresponding again to the Blaeu.Norembega

Norembega or Nurembega appears in what is today New England. This mysterious land began being mapped with Verrazano's 1529 manuscript chart of America. He used the term, Oranbega, which in Algonquin means something on the order of 'lull in the river'. The first detailed reference to Nurumbeg, or as it is more commonly spelled Norumbega, appeared in the 1542 journals of the French navigator Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge, or Jean Allefonsce for short. Allefonsce was a well-respected navigator who, in conjunction with the French nobleman Jean-François de la Roque de Roberval's attempt to colonize the region, skirted the coast south of Newfoundland in 1542. He discovered and apparently sailed some distance up the Penobscot River, encountering a fur-rich American Indian settlement named Norumbega - somewhere near modern-day Bangor, Maine.The river is more than 40 leagues wide at its entrance and retains its width some thirty or forty leagues. It is full of Islands, which stretch some ten or twelve leagues into the sea.... Fifteen leagues within this river there is a town called Norombega, with clever inhabitants, who trade in furs of all sorts; the town folk are dressed in furs, wearing sable.... The people use many words which sound like Latin. They worship the sun. They are tall and handsome in form. The land of Norombega lies high and is well situated.Although Roberval's colony lasted only two years, Andre Thevet, writing in 1550, records encountering a French trading fort at the site of Norumbega.

A few years later, in 1562, an English slave ship wrecked in the Gulf of Mexico. David Ingram, one of the survivors, claimed to have trekked overland from the Gulf Coast to Nova Scotia, where he was rescued by a passing French ship. Possibly inspired by Mexican legends of El Dorado, Cibola, and other lost cities, Ingram returned to Europe to regale his drinking companions with boasts of a fabulous city rich in pearls and built upon pillars of crystal, silver, and gold. The idea caught on in the European popular imagination, and expeditions were sent to search for the city - including that of Samuel de Champlain.

The legend of Norumbega thus seems to have transitioned from Allefonsce's most likely factual description of a lively American Indian fur trading center to Thevet's French trading fort to Ingram's fabulous paradise dripping in wealth. Allefonsce's description of the American Indians he encountered in Norumbega corresponds well with those of Hudson, who also met a tall, well-proportioned people. Sadly, only a few years later, many of these tribes began to die off at extraordinary rates (over 90% of the population perished) due to horrifying outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases carried by the unwitting European explorers. It seems reasonable that Allefonsce may have stumbled upon a periodic or semi-permanent indigenous fur trading center on the Penobscot. It also seems reasonable that French colonists may have set up their fur trading post at the same site, for it was fur, not gold, that was the real wealth of New England and Norumbega. Alas, it was Ingram's fictitious account, which, though wholly the product of a drunken sailor's imagination, produced the most enduring image of Norumbega.

El Dorado

Merian here maps El Dorado (Manoa al Dorada) on the shores of a large lake in what is today northern Brazil or southern Guyana. Most Europeans believed that the most likely site of El Dorado legend was the mythical city of Manoa located here on the shores of Lake Parima, near modern-day Guyana, Venezuela, or northern Brazil. Manoa was first identified by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595. Raleigh does not visit the city of Manoa (which he believes is El Dorado) himself due to the onset of the rainy season. However, he describes the city, based on indigenous accounts, as resting on a salt lake over 200 leagues wide. This lake, though no longer mapped as such, does have some basis in fact. Parts of the Amazon were, at the time, dominated by a large and powerful Indigenous trading nation known as the Manoa. The Manoa traded the length and breadth of the Amazon. The onset of the rainy season inundated the great savannahs of the Rupununi, Takutu, and Rio Branco or Parima Rivers. This inundation briefly connected the Amazon and Orinoco river systems, opening an annual and well-used trade route for the Manoans. The Manoans, who traded with the Incans in the western Amazon, had access to gold mines on the western slopes of the Andes. So, when Raleigh saw gold-rich Indian traders arriving in Guyana, he made the natural assumption of a gold-hungry European in search of El Dorado. When he asked the Orinocans where the traders were from, they could only answer, 'Manoa.' Thus, Lake Parime or Parima and the city of Manoa began to appear on maps in the early 17th century. The city of Manoa and Lake Parima would continue to be mapped in this area until about 1800.Publication History and Census

This map was executed in 1638 for inclusion in Matthias Merian's Neuwe Archontologia cosmica, a German translation of Pierre d'Avity's 1616 Les Estats, empires, et principautez du monde. We identify about ten examples of later editions of Merian's Neuwe Archontologia cosmica in institutional collections, and twenty examples of this separate map are so cataloged.CartographerS

Matthäus Merian (September 22, 1593 - June 19, 1650), sometimes referred to as 'the Elder' to distinguish from his son, was an important Swiss engraver and cartographer active in the early to mid 17th century. Merian was born in Basel and studied engraving in the centers of Zurich, Strasbourg, Nancy and Paris. In time Merian was drawn to the publishing mecca of Frankfurt, where he met Johann Theodor de Bry, son of the famed publisher Theodor de Bry (1528 - 1598) . Merian and De Bry produced a number of important joint works and, in 1617, Merian married De Bry's daughter Maria Magdalena. In 1623 De Bry died and Merian inherited the family firm. Merian continued to publish under the De Bry's name until 1626. Around this time, Merian became a citizen of Frankfurt as such could legally work as an independent publisher. The De Bry name is therefore dropped from all of Merian's subsequent work. Of this corpus, which is substantial, Merian is best known for his finely engraved and highly detailed town plans and city views. Merian is considered one of the grand masters of the city view and a pioneer of the axonometric projection. Merian died in 1650 following several years of illness. He was succeeded in the publishing business by his two sons, Matthäus (1621 - 1687) and Caspar (1627 - 1686), who published his great works, the Topographia and Theatrum Europeaum, under the designation Merian Erben (Merian Heirs). Merian's daughter, Anna Maria Sibylla Merian, became an important naturalist and illustrator. Today the German Travel Magazine Merian is named after the famous engraver. More by this mapmaker...

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571 - October 18, 1638), also known as Guillaume Blaeu and Guiljelmus Janssonius Caesius, was a Dutch cartographer, globemaker, and astronomer active in Amsterdam during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Blaeu was born 'Willem Janszoon' in Alkmaar, North Holland to a prosperous herring packing and trading family of Dutch Reformist faith. As a young man, he was sent to Amsterdam to apprentice in the family business, but he found the herring trade dull and instead worked for his cousin 'Hooft' as a carpenter and clerk. In 1595, he traveled to the small Swedish island of Hven to study astronomy under the Danish Enlightenment polymath Tycho Brahe. For six months he studied astronomy, cartography, instrument making, globe making, and geodesy. He returned to Alkmaar in 1596 to marry and for the birth of his first son, Johannes (Joan) Blaeu (1596 – 1673). Shortly thereafter, in 1598 or 1599, he relocated his family to Amsterdam where he founded the a firm as globe and instrument makers. Many of his earliest imprints, from roughly form 1599 - 1633, bear the imprint 'Guiljelmus Janssonius Caesius' or simply 'G: Jansonius'. In 1613, Johannes Janssonius, also a mapmaker, married Elizabeth Hondius, the daughter of Willem's primary competitor Jodocus Hondius the Elder, and moved to the same neighborhood. This led to considerable confusion and may have spurred Willam Janszoon to adopt the 'Blaeu' patronym. All maps after 1633 bear the Guiljelmus Blaeu imprint. Around this time, he also began issuing separate issue nautical charts and wall maps – which as we see from Vermeer's paintings were popular with Dutch merchants as decorative items – and invented the Dutch Printing Press. As a non-Calvinist Blaeu was a persona non grata to the ruling elite and so he partnered with Hessel Gerritsz to develop his business. In 1619, Blaeu arranged for Gerritsz to be appointed official cartographer to the VOC, an extremely lucrative position that that, in the slightly more liberal environment of the 1630s, he managed to see passed to his eldest son, Johannes. In 1633, he was also appointed official cartographer of the Dutch Republic. Blaeu's most significant work is his 1635 publication of the Theatrum orbis terrarum, sive, Atlas Novus, one of the greatest atlases of all time. He died three years later, in 1638, passing the Blaeu firm on to his two sons, Cornelius (1616 - 1648) and Johannes Blaeu (September 23, 1596 - December 21, 1673). Under his sons, the firm continued to prosper until the 1672 Great Fire of Amsterdam destroyed their offices and most of their printing plates. Willem's most enduring legacy was most likely the VOC contract, which ultimately passed to Johannes' son, Johannes II, who held the position until 1617. As a hobbyist astronomer, Blaeu discovered the star now known as P. Cygni. Learn More...