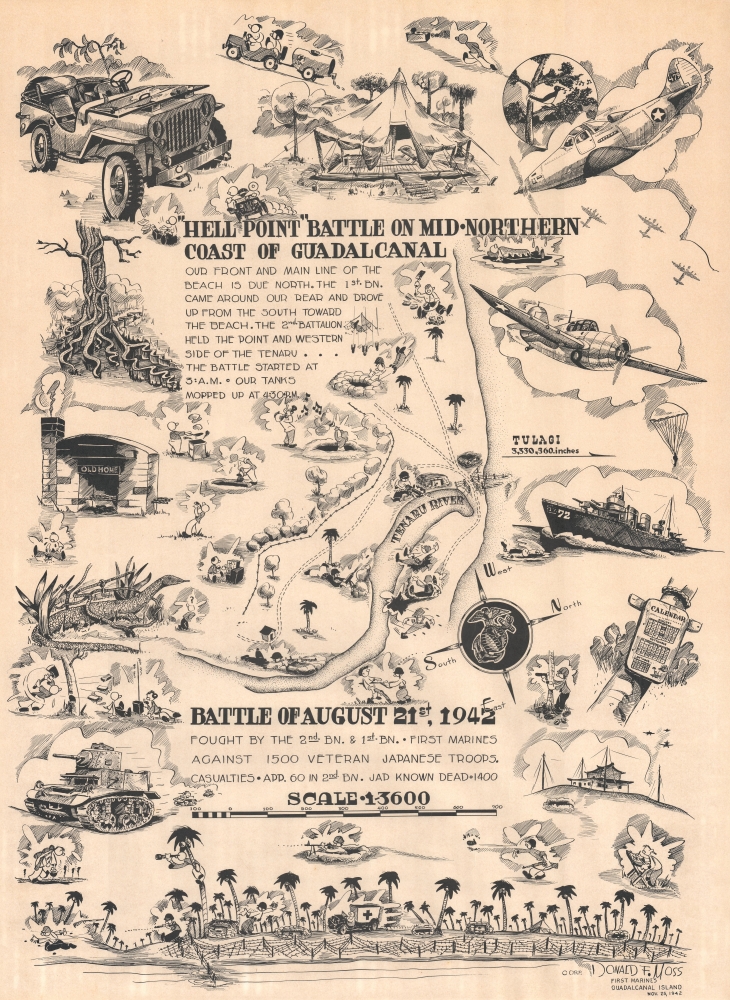

1943 Moss Pictorial Map of the WWII Battle of Hell's Point, Guadalcanal

HellPoint-moss-1943-2

Title

1943 (dated) 26.5 x 19 in (67.31 x 48.26 cm) 1 : 3600

Description

A Closer Look

The depiction of the battle appears at center, with illustrations of Marines firing at the enemy. Moss also includes an illustration of a Marine bayonetting a Japanese soldier. Vignettes of Marine life on Guadalcanal surround the battle scene. Some highlight more mundane activities, including cooking, chopping wood, typing reports, carrying gear, and even an artist drawing something! (Possibly Moss?) Other illustrations capture important aspects of the Marine's fight for Guadalcanal, including depictions of jeeps, tents, a P-39 Airacobra in the upper right corner, an F4F Wildcat, a Stuart tank, and a Navy Destroyer. The illustration along the bottom is likely meant to depict Henderson Field, the airfield on Guadalcanal that the Japanese were building, and the Americans invaded the island to capture. The entire base is surrounded by barbed wire, and several Marines appear defending the base with one up a palm tree looking through a spyglass!The Battle at Hell's Point

On August 19, two days before the battle, Marine infantrymen attacked and killed a Japanese patrol of 31 soldiers. These Japanese soldiers wore clean uniforms, marking them as new arrivals to Guadalcanal. When the Marines searched the Japanese, they discovered numerous documents, some of which were maps that showed the American positions with surprising accuracy and detail. These maps, combined with the fact that the Japanese were wearing clean uniforms, informed the Marines that new Japanese troops had landed on Guadalcanal and that they were likely to attack. The decision was made not to attack the Japanese, but to defend the territory the Marines already held. Marines fortified their lines, part of which was a sandbar that came to be known as Hell's Point.Hell's Point was a spit of land that separated Alligator Creek (which was actually a tidal lagoon and inhabited by crocodiles, not alligators) from Sealark Channel and ranged from 25 to 50 feet wide and was about 100 feet long. It also rose only 10 feet above the water. Several platoons fortified this land with .30- and .50-caliber machine guns, antitank guns, and rifle infantry. Logs and sandbags provided cover with barbed wire (strung without the benefit of gloves) strung to impede enemy progress. Marines also dug in at the center and fortified the river approaches.

The Japanese attacked between 2:00 a.m. and 3:00 a.m. on August 21, expecting to easily defeat the Marines. While surprised by the entrenched position so far from Henderson Field (the Marines airstrip on Guadalcanal), the Japanese commander ordered the attack. The Marines kept up a wall of machine gun and rifle fire, only losing a few positions but quickly recapturing them.

As morning broke, the carnage of the previous night became apparent. Nonetheless, the confident Japanese did not retreat, hunkering down to assault the American position again after darkness fell. However, the Marines were not keen to let them sit and wait. Instead, the Marines attacked on both sides of the river, sending a battalion reinforced with Stuart light tanks across the river further upstream while several rifle companies attacked from positions at Hell's Point. The tanks proved decisive, as the Japanese did not have any antitank weapons. By late afternoon, the battle was over, which came to be known as the Battle of the Tenaru River, and 1400 of the 1500 Japanese soldiers had been killed.

The Guadalcanal Campaign

The months-long battle for Guadalcanal occurred at a critical moment in the Pacific War. The Allies inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese at Midway, but the overall situation remained uncertain. The Japanese advance through Southeast Asia continued while their aggressive progress in the Pacific threatened Allied communication and supply lines.In May 1942, the Japanese occupied Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, where, using Korean forced labor, they began constructing an airbase. Recognizing a serious threat to shipping, the Allies accelerated plans to retake the island. The invasion initially proceeded smoothly, with Marines seizing the offending airfield, which they renamed Henderson Field. Japanese forces retreated into the surrounding jungles and mountains. Meanwhile, retaliatory air strikes forced Allied supply ships to retreat, leaving the Marines at Henderson Field stranded with limited supplies. From their mountain and jungle hideouts, Japanese forces began a guerilla war to retake the island.

From mid-August 1942 through January 1943, land, sea, and air battles raged as both sides committed to controlling Guadalcanal. Tenacious Japanese attacks failed to dislodge the entrenched Americans while depleting Japanese forces faster than they could be reinforced. By late October, the Marines began doggedly expanding their perimeter into the surrounding jungles. By the end of December, the Japanese began a full retreat.

In the end, both sides suffered staggering losses, the Allies mostly at sea and the Japanese mostly on land. However, Allied losses were easily replaced while Japan lacked the population and industrial capacity to replenish its own forces. By committing so heavily to Guadalcanal, the Japanese diverted resources from other campaigns, allowing the Allies to take the initiative. Following Guadalcanal, the Pacific War shifted in the favor of the Allies.

Publication History and Census

This map was drawn by Donald F. Moss while he was in the Marine Corps and published in 1943 in the United States. This piece has generally been ignored by institutions and does not appear in OCLC. We note only a handful of auction records over the past 20 years.Cartographer

Donald Francis Moss (January 20, 1920 - May 18, 2010) was an American artist and U.S. Marine Corps veteran. Born in Somerville, Massachusetts, Moss grew up in Melrose, a small city 7 miles north of Boston. His passion for capturing sports in art began in high school, when he designed posters that earned him a scholarship to Vesper George Art School, then a prominent institution in Boston, Massachusetts. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1940 and became a Corporal in E. Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. He landed on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands with the Marines on August 7, 1942, and fought on Guadalcanal until it was secured. He also fought on New Britain at Cape Gloucester. Moss drew sketches and painted watercolors of his fellow soldiers, many of which he gave to his subjects who then sent them home as a glimpse of what life was like for a Marine. Once his artistic talent was discovered by the Marine Corps, he was assigned to the Intelligence Section to make maps for the Marines and the Army Air Corps. After the war, Moss moved to New York and enrolled at the Pratt Institute on the GI Bill. He soon began working as a freelance artist creating work for Colliers, Esquire, and Good Housekeeping. He received his first assignment from Sports Illustrated in 1954, beginning a 30-year relationship with the magazine that made Moss one of the most well-known and successful American sports artists. He created more covers and editorial art for Sports Illustrated than any other artist. His last Sports Illustrated cover was published in 1984. He also created work for Olin Skis, Head tennis racquets, and he designed the official poster for Super Bowl XII. He also created work for the Olympics and designed a dozen postage stamps. He was named 1985 Sport Artist of the Year and his art hangs in the American Sport Art Museum and Archives. He designed part of the Guadalcanal American Memorial. Moss married Virginia Haderty Moss, with whom he had three children. More by this mapmaker...