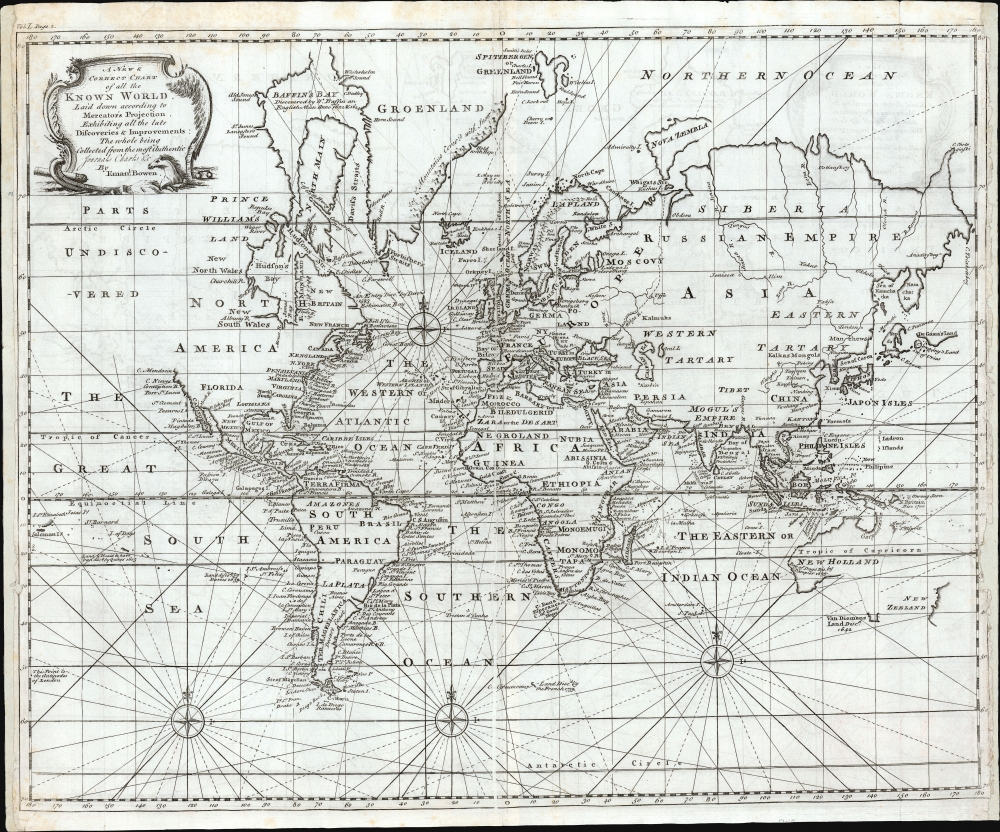

1744 Bowen Map of the World on Mercator Projection (Sea of Korea identified)

WorldMercator-bowen-1744

Title

1744 (undated) 14.25 x 17.75 in (36.195 x 45.085 cm) 1 : 100000000

Description

A Short-Lived Edition

Specifically described as a chart, not a map, this work offers limited inland detail; nevertheless, many major cities, geographical landmarks, and regions are noted beyond the more thoroughly-detailed coastlines. It is worth noting that the present work was relatively swiftly replaced: subsequent editions of Bowen's A Complete System of Geographycontained a completely reengraved chart. The choice to do so was material, not aesthetic (indeed, the engraving of this 1744 map is notably finer than on the map that replaced it.) The most readily apparent revision in 1747 is the addition of Edmond Halley's revised lines of magnetic variation. While no doubt an aid to navigation, this is too small to be functional as a true nautical charge. Bowen more likely instituted these changes in order to navigate treacherous waters of a political nature.The Contentious Search for a Northwest Passage

The search for a Northwest Passage to circumvent the inconvenience of North America began in the 16th century. 1741 opened a particularly vicious chapter in that search. The Parliamentarian, soldier, and eventual governor of North Carolina Arthur Dobbs (1689 - 1765) had long waged a campaign to have the Hudson's Bay Company monopoly revoked on the grounds that their protection of that monopoly led them to stifle exploration, and that they were hiding the existence of a Northwest Passage. In order to reveal the secrets that the company was doubtless concealing, Dobbs convinced the Royal Navy and the Royal Society to send an expedition to Hudson's Bay. He selected Christopher Middleton - formerly of the Hudson's Bay Company - to command the mission, which sailed up the west shore of the Bay in an effort to reveal passages to the Pacific supposed to be found there. None exist, and the most promising large inlet he examined (just south of Repulse Bay) he would name Wager Bay, fed by a river to which he would apply the same name. The present chart uses Wager River to refer to this feature, found just south of Repulse Bay.Dobbs, furious that his handpicked captain presented evidence contrary to his doggely-held beliefs, accused Middleton of conniving a fraud with his former employer, the Hudson Bay Company. Worse yet, Dobbs was able to pressure several of Middleton's subordinates into testifying against their captain with the claim that Wager Inlet was, in fact, a Strait, ultimately believed to connect with the Pacific. A follow up voyage - commanded by one of Middleton's treacherous officers - would return in 1747 with the unwelcome news that Middleton's report had been correct, and that Dobbs had been wrong. Bowen's 1747 edition of his world map was produced prior to this latter report - and so it had changed the original Wager River to Dobbs' preferred Wager Strait, along with an obsequious 'C. Dobbs.' The 1747 version of the map would also include the 'Supposed Strait of Anian,' a hopeful connection between the fraudulent Wager Strait and the Pacific. No such reference to Anian appears on this 1744 plate. Thus, the present 1744 map, reflecting the truthful discoveries of Middleton, was replaced in 1747 with a document supporting Dobb's fraud.

Australia

This map is also interesting for its treatment of the South Pacific and Australia. Bowen issued this map during a dark period in Australian exploration, the 70-some years between the navigations of William Dampier (1699) and Tobias Furneaux (1773). Consequently, most of the cartography dates to 17th-century Dutch expeditions to Australia's western coast, including those of Abel Tasman and William Janszoon. The speculative mapping includes Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) and New Guinea attached to the Australian continent. The unexplored eastern coast of the continent is mapped as a dotted line running from New Guinea directly south to the tip of Tasmania.The Discoveries of Quiros

New Zealand appears in a very embryonic form as a single landmass with no western shore. This most likely conforms to Abel Tasman's 1642 sighting of the western coast of South Island. Just to the north of New Zealand yet another mysterious landmass appears, 'Ter d' St. Esprit.' This is an enlargement of the New Hebrides as discovered by the Spanish explorer and religious zealot Pedro Fernandez di Quir, or Quiros. Quiros, believing he had discovered the long-speculated southern continent of Terre Australis, mapped the islands larger than fact. Another smaller island group appears far to the east (lower left) is also labeled after Quiros: 'Land or Islands said to have been discovered by Quiros 1605'. Secretive, self-delusional, fanatical, and inept, Quiros made charts that bordered on fictional. It took several hundred years and no less a navigator than James Cook to decipher what Quiros actually discovered.Siberia and Northwestern North America

Though Siberia exhibits considerable detail consistent with Vitus Bering's 1728 explorations, on the opposite side of the Strait, in America, Bowen concedes the entire Pacific Northwest as 'Parts Undiscovered.'De Gama Land

Also of interest is Bowen's mapping of 'De Gama's Land' of Terre de Compagnie, just to the south of Siberia. Gama or Gamaland was supposedly discovered in the 17th century by a mysterious figure known as Jean de Gama. Various subsequent navigators claim to have seen this land, but it was left to Bering to finally debunk the myth. In 1729, he sailed for three days looking for Juan de Gama Land but never found it. At times it was associated with Hokkaido and at other times with the mainland of North America. Bowen clearly does not give up on the idea. The truth of Gama is most likely little more than a misinterpretation of the Aleutian Archipelago as a single body of land. It continued to appear in numerous maps for about 50 years following Bering's voyages until the explorations of Cook confirmed the Bering findings.Hokkaido

The mapping of Hokkaido (here identified as Yedso) joined to Sakhalin refers to the cartography of Maerten de Vries and Cornelis Jansz Coen, who explored this land in 1643 in search of gold and silver islands of Spanish legend. Vries and Coen were the first Europeans to enter these waters, then little known even to the Japanese. They mapped the Strait of Vries, identified here. They believed this strait to separate Asia from America, of which Compagnies Land formed part, thus elucidating its magnificent proportions. They were also the first European navigators to discover Sakhalin and map its southern coastline. Apparently, the Castricum was mired in a heavy fog as it attempted to explore these seas. Thus, Vries and Coen failed to notice the strait separating Yedo (Hokkaido) from Sakhalin, initiating a cartographic error that would persist well into the 18th century. Despite their many successes, the expedition ultimately failed to discover islands of silver and gold, thus proving definitively to Van Diemen that no such lands ever existed.The Sea of Korea

The sea between Japan and Korea, whose name, either the 'Sea of Korea,' 'East Sea,' or the 'Sea of Japan,' is here identified in favor of Korea (Sea of Corea). Korea has used the term 'East Sea' since 59 B.C., and many books published before the Japanese annexed Korea make references to the 'East Sea' or 'Sea of Korea'. Over time, neighboring and western countries have identified Korea's East Sea using various terms. The St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences referred to the East Sea as 'Koreiskoe Mope' or 'Sea of Korea' in their 1745 map of Asia. Other 17th and 18th century Russian maps alternate between 'Sea of Korea' and 'Eastern Ocean.' The 18th-century Russian and French explorers Adam Johan von Krusenstern and La Perouse called it the 'Sea of Japan,' a term that became popular worldwide. Nonetheless, the last official map published by the Russians named the East Sea the 'Sea of Korea.' The name is currently still a matter of historical and political dispute between the countries.Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by Emanuel Bowen for the 1744 edition of A Complete System of Geography. The map was replaced with a new plate for the 1747 edition of the work. This 1744 plate is scarce; despite examples appearing on the market from time to time, only one separate example is cataloged in OCLC, at the National Library of Australia. Bowen's A Complete System of Geography is well-represented in institutional collections.Cartographer

Emanuel Bowen (1694 - May 8, 1767) had the high distinction to be named Royal Mapmaker to both to King George II of England and Louis XV of France. Bowen was born in Talley, Carmarthen, Wales, to a distinguished but not noble family. He apprenticed to Charles Price, Merchant Taylor, from 1709. He was admitted to the Merchant Taylors Livery Company on October 3, 1716, but had been active in London from about 1714. A early as 1726 he was noted as one of the leading London engravers. Bowen is highly regarded for producing some of the largest, most detailed, most accurate and most attractive maps of his era. He is known to have worked with most British cartographic figures of the period including Herman Moll and John Owen. Among his multiple apprentices, the most notable were Thomas Kitchin, Thomas Jeffreys, and John Lodge. Another apprentice, John Oakman (1748 - 1793) who had an affair with and eventually married, Bowen's daughter. Other Bowen apprentices include Thomas Buss, John Pryer, Samuel Lyne, his son Thomas Bowen, and William Fowler. Despite achieving peer respect, renown, and royal patronage, Bowen, like many cartographers, died in poverty. Upon Emanuel Bowen's death, his cartographic work was taken over by his son, Thomas Bowen (1733 - 1790) who also died in poverty. More by this mapmaker...