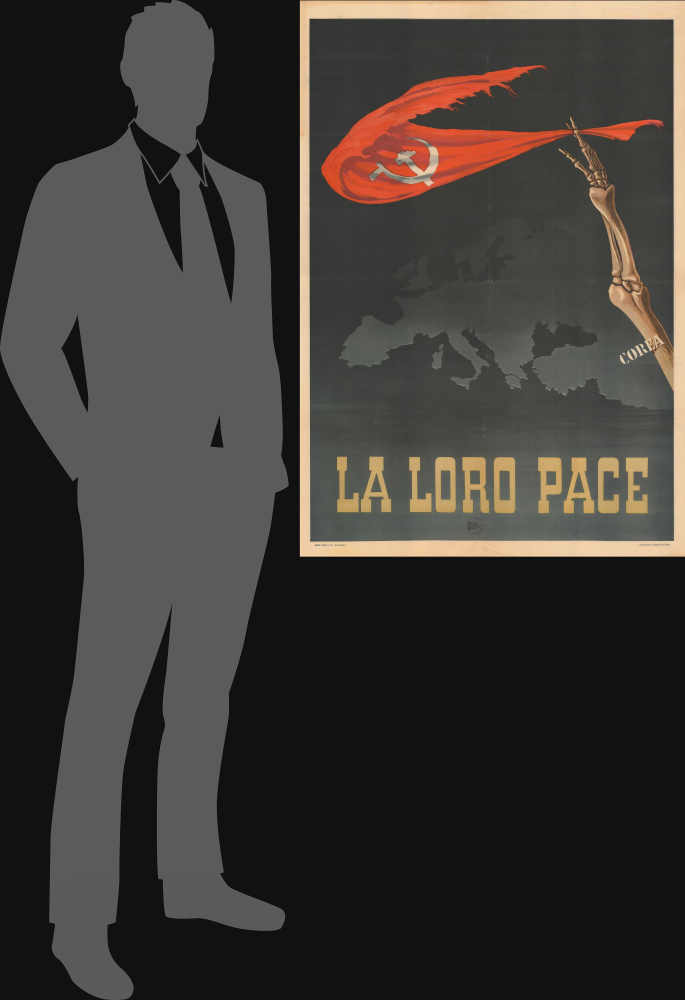

1953 Gros Monti Persuasive Anti-Communist Map of Europe, Korean War

LaLoroPace-grosmonti-1953

Title

1953 (undated) 39 x 27 in (99.06 x 68.58 cm) 1 : 12000000

Description

A Closer Look

This haunting poster presents a map of Europe and the Near East, centered roughly on Italy. At right, a skeleton's arm labeled 'Korea' holds a tattered Communist banner. At the bottom, in large letters, is the phrase 'Their Peace.' Although undated, the poster was likely produced during the long Korean War armistice negotiations (July 1951 - July 1953). As the armistice negotiations were concluding, Italy held its first general election in five years (discussed below), and this poster was mostly likely issued at this time to support the Christian Democrats and other anti-Communist parties.Korea and the Risk of a European War

As the Second World War drew to a close and early tensions began to arise between the wartime Allies, considerable effort was made, particularly with the July - August 1945 Potsdam Conference, to jockey for position but also avoid a situation that could lead to another war in the future; the Soviets and Europeans were exhausted by the war against Germany and Stalin was confident that a confrontation with capitalism could wait until the Soviets had recovered. The division of Germany into occupation zones and the shifting of borders in Eastern Europe were the major agenda items at Potsdam. However, some attention was given to the ongoing war in Asia, which the Soviets pledged to join three months after the conclusion of the war in Europe on August 9.Wartime discussions on the future of Korea were scant, and the lightning Soviet advance through Manchuria upon entering the Pacific War concerned Washington D.C. This reality led to a proposal for the division of the peninsula into occupation zones being rapidly prepared and presented to the Soviets, who unexpectedly accepted it without complaint. (The Soviets were, in fact, incapable of and uninterested in keeping a large occupation force in Korea, unlike they were Eastern European countries.) In the following months, as tensions between the Soviet Union and the West mounted, both Korea and Germany drifted towards political division along the lines of the occupation zones.

While Europe remained the primary area of concern for both the Soviets and Americans, other parts of the world became proxies for the developing global rivalry. It was the misfortune of Korea to become the first intense 'hot' war of the Cold War, which left the country divided and devastated. Following a very dynamic situation in the first year of the war - with the North Koreans making rapid gains in the south, then being counter-attacked by the U.S.-led United Nations forces, then China entering the war and successfully counter-attacking the American and South Korean troops - by the summer of 1951 the war had settled into a stalemate around the original dividing line at the 38th parallel north. Armistice negotiations began in July 1951 but dragged on for months and months as neither side wanted to end the war without at least recovering their full pre-war territory.

The war ground down the major outside powers engaged, the U.S. and the People's Republic of China, and became a major political liability for President Harry Truman. It is often assumed that Stalin also hoped to drag the war out to distract the U.S. from other theaters, particularly Europe; there is little direct evidence of this (Stalin generally kept his strategic calculations to himself), and Stalin was primarily concerned for the moment with avoiding the outbreak of a wider war. However, it would have been consistent with his calculated global perspective on the anti-capitalist and 'anti-imperialist' struggle. Regardless, the archival record indicates that both the Koreas and China were resistant to an armistice for much of this period; the Chinese believed they could outlast the Americans and secure a better agreement later. (The U.S. and North Korea/China were also bitterly divided over the issue of returning prisoners of war, mostly because the U.S. had offered Chinese prisoners the option of going to Taiwan and North Korean prisoners the option to remain in South Korea.) In any event, in the weeks after Stalin's death on March 5, 1953, the new Soviet leadership pushed both Mao Zedong and Kim Il-sung to agree to an armistice and focus on reconstruction.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Soviet-backed coups or effective coups brought the countries of Eastern Europe, which were also under Soviet occupation, clearly into the Communist camp. In early postwar elections in Western Europe, Communist and Communist-aligned parties gained a considerable share of the electorate, although never enough to control the government and take over the system. Anti-Communist parties, which had to distance themselves from any association with wartime fascist or fascist-aligned regimes, were increasingly supported by the new American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), including through the production of propaganda posters such as the present one. Italy was a particular concern for the West, and the general elections of April 18, 1948, became a showdown between Soviet and American influence on the continent. The anti-Communist Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana, or DC for short) received the largest share of the vote in 1948 and would dominate elections for years afterward, helping institute Italy's postwar economic miracle.

However, the specter of Communism and a European war hardly disappeared. In the closing stages of the Korean War Armistice negotiations, Italy held its first general election since the consequential 1948 elections. The benefits of the Marshall Plan and Italy's recovery from the war had not been fully felt, and much of the country remained poor, with black markets flourishing. The DC had also pushed through an unpopular election law that provided bonus seats in the Italian Parliament to the party garnering a majority or plurality of votes (sure to be the DC themselves), greatly disadvantaging the Communists and other minority parties, including the DC's coalition partners. Therefore, despite an improving economy, continued American support, and strong anti-Communist messaging from the Catholic Church, the Communists were expected to gain a significant share of the electorate and won 22.6 percent of the vote (down from the roughly 31 percent they won as part of a Soviet-aligned coalition in 1948).

Publication History and Census

This propaganda poster was prepared by the firm Gros Monti, most likely in the weeks before the 1953 Italian General Election. The company's founder, Mario Gros, was a master of vivid and striking chromolithographic posters, including some propaganda works for Italy's fascist regime (see biography below). This work is very scarce; we are aware of only one other surviving example, held by the Museo Nazionale Collezione Salce in Treviso.Cartographer

Mario Gros (1888 - 1977) was an Italian painter, artist, graphic designer, and entrepreneur. Born in Torino (Turin), Gros showed artistic skill from a young age and apprenticed as an engraver while attending the local art school Accademia Albertina, where he studied with painters Giovanni Guarlotti (1869 - 1954) and Romolo Bernardi (1876 - 1956). After completing art school, he began work as a chromolithographic engraver (artist), mainly designing advertising posters. He then designed movie posters for the film studios Pittaluga and Ambrosio, depicting many of the early stars of Italian cinema and dubbed Italian versions of major foreign films. In 1925, he and two partners founded their own firm, Gros Monti and Company. Overcoming some early difficulties, the company eventually flourished, signing major clients such as Fiat, producing posters for local municipalities, and expanding to Rome. However, the company's printworks was destroyed in a bombing in 1942. Although not the most prolific producer of propaganda for Mussolini's fascist regime, the firm also produced some propaganda works. In the postwar period, the company was relaunched and eventually (c. 1954) changed its name to Mario Gros and Company. It found renewed success with advertising, capturing the heady atmosphere of the postwar economic miracle, and some (anti-Communist) political posters, in the process bringing in a new generation of artists such as Armando Testa (1917 - 1992). More by this mapmaker...