This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1851 Tallis / Rapkin Map of Tibet, Mongolia, and Manchuria; China, Qing Empire

Mongolia-tallis-1851

Title

1851 (undated) 10.5 x 13.5 in (26.67 x 34.29 cm) 1 : 19008000

Description

A Closer Look at the Map

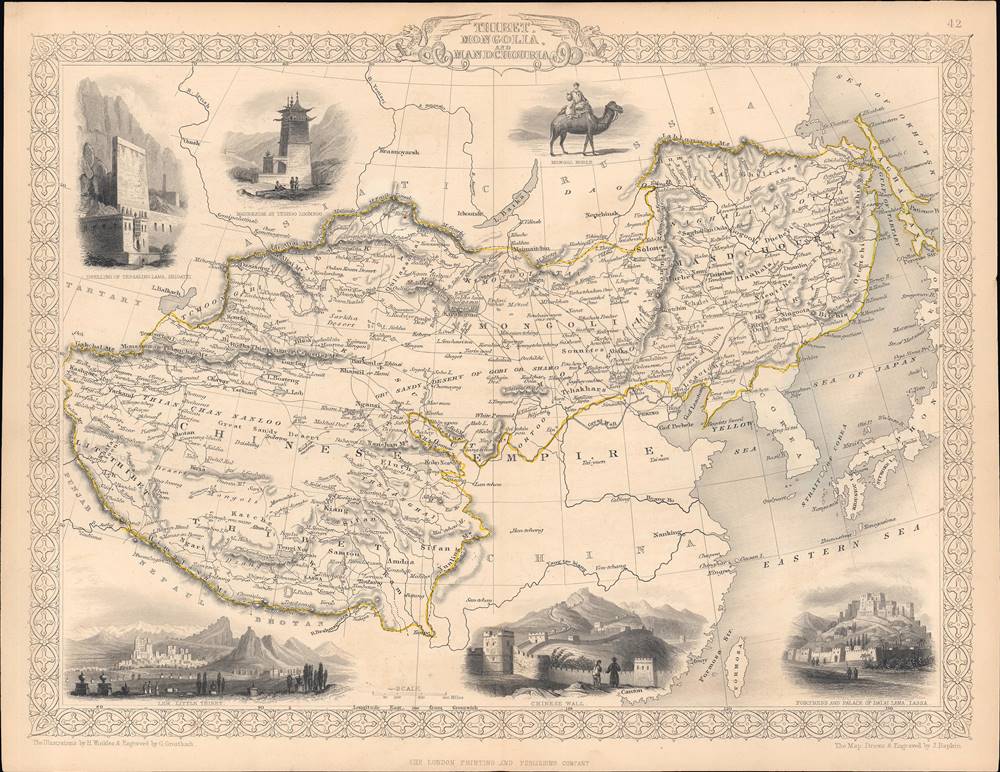

This map shows the portions of the Qing Empire outside of 'China proper' (roughly the areas ruled by the Ming, who the Qing replaced), including Tibet, Mongolia, Manchuria (homeland of the Qing), and the Qing-ruled areas of Central Asia, known contemporaneously as Chinese Turkestan, and from the late 19th century as Xinjiang. The border between Russia and China here predates the Treaty of Aigun (1858), which ceded lands north of the Amur River to Russia, while the border between British client states in India and the Qing Empire were highly uncertain at this point.The map uses a mélange of Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan, and Turkic names (for example, Kirin Oula for Jilin), in some cases likely a legacy of earlier European maps (such as d'Anville's influential 1737 map). Elsewhere, Chinese terms are used (such as Thian Chan Nanloo 天山南路) or intermingled with English, Manchu, Turkic, or Mongol names, as with 'Great Sandy Desert of Gobi or Shamo' (沙漠) and Koko Nor with Thsianghai (青海) written below it.

A set of illustrations surround the map, which are, clockwise from top-left: the dwelling of the Tessaling Lama, Shigatzi (that is, the Panchen Lama and the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in Shigatse), the mausoleum of Teshoo Loomboo (Tashi Lhunpo), a Mongol noble, the fortress and palace of the Dalai Lama, Laasa (Potala Palace, Lhasa), the 'Chinese Wall' (Great Wall of China), and Leh ('Little Tibet') in Ladakh, a kingdom under partial Tibetan control in the late 17th and 18th century, but which was invaded and annexed by the Sikh Empire, included in Jammu, and subsequently the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Qing Rule of Non-Chinese Areas

Qing rule in China proper and the non-Chinese parts of the empire differed considerably, but both were rooted in a model of accommodation to local customs and practices. The Qing Emperors went to great lengths to demonstrate their patronage and sophistication by appealing to the various cultures throughout the empire. Thus, they learned classical Chinese to impress Confucian scholars, while in Tibet they cultivated a relationship with the Panchen and Dalai Lamas and built grand monasteries to show their devotion to Buddhism.As China proper contained the bulk of the empire's wealth and population, it attracted the lion's share of the emperors' attention, but the non-Chinese parts of the empire constituted roughly half its territory and were essential for frontier defense. This explains not only the Qing endorsement of local religious and cultural figures, but also a keen interest in, for example, the disputes between Tibet and neighboring kingdoms like the Gorkha Kingdom and Ladakh.

The Qing system of accommodation and loose rule over frontier populations was a clever imperial strategy, but was unsustainable in the face of foreign imperialism backed by modern weapons. The Qing adapted by trying, and only partially succeeding, in establishing sovereignty over these regions, leaving a complex legacy that has caused problems of oppression and resistance down to the present.

The status of these regions under Qing rule remains a matter of historical debate, in large part due to its significance for contemporary political and territorial issues. The Manchus were especially close with certain Mongol tribes, who composed a significant component of the Qing Banner System, and consequently leading officials and soldiers of the empire. However, other Mongol tribes, particularly those further from Manchuria like the Oirats, were not ready to submit to Qing suzerainty. The Oirat-led Dzungar Khanate was a formidable empire in its own right and remained a threat on the Qing frontier for decades after the Manchus conquest of China.

At the very start of Qing rule over China, the 5th Dalai Lama, who had himself just helped reunified Tibet in tandem with a Dzungar general named Güshi Khan, came to Beijing to recognize the spiritual authority of the Qing. In practical terms, however, Tibet functioned independently as it had under the Ming. When Dzungars opposed to the descendants of Güshi Khan and the Dalai Lamas invaded Tibet in 1717, the Qing sent an army to expel them, and stationed officials called 'ambans' in Lhasa. However, Qing rule over Tibet remained very limited, although the Qing did in theory oversee the selection of reincarnations of the Panchen and Dalai Lamas (the Golden Urn system). They also intervened when Tibet was invaded by the Nealese Gorkha in the late 1780s - early 1790s and in another war against Nepal in 1855 – 1856, as well as several smaller engagements. However, the Qing's ability to claim control over Tibet was severely weakened in the wake of the Opium Wars and multiple rebellions.

As for the area that would become known as Chinese Turkestan, the Dzungars were weakened by internal succession disputes that the Qing were able to exploit, and were also being pressed from the north and west by the Russian Empire. The Qing were able to subjugate the Dzungars in 1755, aiming to institute a system of indirect rule similar to what existed for Tibet and Mongolia. But an uprising in 1757 led to another military campaign that took a serious toll on the civilian population of the region due to massacres and disease, to the extent that some scholars have deemed it a genocide (the Qianlong Emperor was particularly infuriated by the uprising and repeatedly ordered his commanders to exterminate the Dzungars). Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin were declared part of China by the Qianlong Emperor, but rule remained indirect through local elites until another large uprising in the 1860s – 1870s, which briefly expelled the Qing entirely. After some deliberation, the Qing decided to reconquer the western regions, now renamed Xinjiang, rule it through a Chinese-style Confucian bureaucracy, and work towards Sinicizing the inhabitants.

Anglo-Russian-Japanese Competition

In the decades following this map's publication, both British and Russian interest in these regions increased, as part of their 'Great Game' imperial competition. Ambitious young explorers set off on expeditions to map the landscape and reconnoiter the opposite side's capabilities. The British officer Francis Younghusband and the Russian officer Bronislav Grombchevsky travelled throughout Central and Inner Asia in the 1880s – 1890s, even crossing paths at one point in a surprisingly amicable meeting. But by the 1890s, the British had the upper-hand in the contest. One of Younghusband's interpreters, the half-Chinese George Macartney (馬繼業), stayed in Kashgar as the expedition passed through in 1890 and established a British Consulate that became a conduit for gathering intelligence and exercising influence in the region (he was a relative of George Macartney, who led a failed British embassy to China in 1792, and was the partial namesake of the Macartney-MacDonald Line, important in current border disputes between India and China). However, following the establishment of the Soviet Union and Soviet Republics in Central Asia, along with the collapse of the Qing, Soviet influence in Xinjiang expanded.As for Tibet, Younghusband returned with a military expedition in 1903 – 1904, ostensibly to settle border questions between Tibet and Sikkim, but in reality to force a treaty on Lhasa that would prevent any Russian influence in Tibet. Recognizing the mission's true purpose, Tibetan forces resisted, but to little effect against the well-armed and trained British troops. The resulting Convention of Lhasa (1904) allowed the British to establish trading posts in Tibet, forced Lhasa to pay a hefty indemnity, and forbade any (non-British) foreign influence in Tibet. The Anglo-Chinese Convention two years later reduced the indemnity and other onerous terms of the 1904 agreement (instead demanding an indemnity from the Qing) and reasserted Qing suzerainty in Tibet. However, the reassertion of Qing control was transitory and Tibet was effectively independent once the Qing collapsed in 1912.

In Mongolia, as many Mongol tribes had allied with the Qing in the 17th century, they were able to maintain their autonomy for much of the Qing era and serve throughout the empire as soldiers and officials. However, overpopulation and natural disasters in the Chinese interior sent migrants and refugees streaming to the Mongolian frontier in the 18th and 19th century. Convicts were also often exiled to Mongolia as a form of punishment. The Qing initially tried to limit migration but later encouraged it in Inner Mongolia, where the Mongols quickly became a minority in their own land. When the Qing collapsed, the new Chinese Republic claimed Outer Mongolia as Chinese territory, leading Mongolian nobles to seek foreign assistance wherever they could, aligning first with White Russians and then the Soviets, resulting in the establishment of the Mongolian People's Republic. In Inner Mongolia, residual bitterness about being forcibly incorporated into China led to a group of Mongolian nobles to ally with Imperial Japan in the 1930s, forming the puppet state of Mengjiang.

In Manchuria, the homeland of the Manchus, the Qing faced a similar but even more acute dilemma as in Mongolia. Keen to protect their ancestral homeland but also eager to avoid unrest in the Chinese interior, the Qing at first reluctantly tolerated and then openly allowed Chinese migration to Manchuria in the 19th century, completely altering the demographics of the region. Even worse, in the last years of the dynasty, Russia and Japan vied for influence in Korea and Manchuria, resulting a series of concessions, including the China Eastern Railway, the South Manchuria Railway, and the Kwantung Leased Territory. By the end of the Qing, Chinese sovereignty over Manchuria was deeply compromised and by 1932 a Japanese puppet state, nominally ruled by the last Qing Emperor Aisin Gioro Puyi, was established.

Publication History and Census

This map was part of the well-known Tallis's Illustrated Atlas and Modern History of the World published in 1851. It was drawn and engraved by John Rapkin, the vignette illustrations were drawn by Henry Winkles and engraved by George Greatbach, and it was published by the London Printing and Publishing Company. It is held by several libraries in North America, Great Britain, and in former territories of the British Empire.CartographerS

John Tallis and Company (1838 - 1851) published views, maps, and atlases in London from roughly 1838 to 1851. Their principal works, expanding upon the earlier maps of John Cary and Aaron Arrowsmith, include an 1838 collection of London Street Views and the 1849 Illustrated Atlas of the World. The firm’s primary engraver was John Rapkin, whose name and decorative vignettes appear on most Tallis maps. Due to the embellishments typical of Rapkin's work, many regard Tallis maps as the last bastion of English decorative cartography in the 19th century. Although most Tallis maps were originally issued uncolored, it was not uncommon for 19th century libraries to commission colorists to "complete" the atlas. The London Printing and Publishing Company of London and New York bought the rights for many Tallis maps in 1850 and continued issuing his Illustrated Atlas of the World until the mid-1850s. Specific Tallis maps later appeared in innumerable mid to late-19th century publications as illustrations and appendices. More by this mapmaker...

John Tallis (November 7, 1817 - June 3, 1876) was an English map publisher and bookseller. Born in Stourbridge in Worcestershire, worked in his father's Birmingham agency from 1836 until 1842. Roughly in 1838, Tallis published a collection of London Street Views, and entered into a partnership with his brother Frederick Tallis from 1842 - 1849. Tallis and Company also published the Illustrated Atlas of the World in 1849. Also in 1849, Tallis traveled to New York City where he founded publishing agencies in six American cities. Upon returning from New York, Tallis paid his brother £10,000 for his share of the business, and operated from then on as John Tallis and Company until 1854. By 1853, John Tallis and Company had agencies in twenty-six cities in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada and employed over 500 people. By the end of 1853, Tallis had made the decision to share the burden of running such an extensive company and formed the London Printing and Publishing Company on February 24, 1854, becoming co-managing director with Ephraim Tipton Brain. After a series of setbacks, however, Tallis had to sell his estate and by 1861 was declared bankrupt. He was kept afloat by the kindness of friends and former employees, but none of his 'various ambitious projects' ever worked out for the rest of his life. Tallis married Jane Ball on December 6, 1836 in Birmingham, with whom he lived until her death in 1862. Tallis remarried on June 27, 1863 to Mary Stephens, with whom he had two children. Learn More...

John Rapkin (July 18, 1813 - June 20, 1899) was an English mapmaker and engraver. Born in Southwark, Rapkin was the son of George Rapkin, a shoemaker, and his wife Elizabeth Harfy. Rapkin and his brother Richard both became engravers and his other brother, William Harfy Rapkin, became a copperplate printer. Rapkin produced works for James Wyld and John Tallis, including The United States and the relative position of Oregon and Texas for Wyld around 1845, and a series of eighty maps for Tallis that became 'Tallis's illustrated atlas, and modern history of the world' in 1851. Rapkin married Frances Wilmot Rudell on January 4, 1837, with whom he had at least eight children, some of whom became engravers, including his sons John Benjamin Rapkin (1837 - 1914), Alfred Thomas Rapkin (1841 - 1905), Joseph Clarke Rapkin (1846? - 1912), and Frederick William Rapkin (1859 - 1945). Rapkin operated under the imprint 'John Rapkin and Sons from 1867 until 1883, and was operating as 'John Rapkin and Sons' by 1887. Rapkin died in 1899 at the age of 85 soon after the death of his wife of over sixty years. Learn More...

Henry Winkles (1801 – 1860) was an English illustrator, engraver, and printer, and a pioneer in the use of steel engraving. He was well-known for his prints of buildings, particularly a three-volume series on the cathedrals of England and Wales. Learn More...

George Greatbach (1819 – 1884), sometimes spelled Greatbatch, was an English engraver and illustrator, same as his brother William (1802 - 1894), with whom he sometimes published as 'Messrs Greatbach.' Learn More...