1909 Pictorial View and Game of the North Pole, Peary Expedition

NorthPoleParty-saalfield-1909

Title

1909 (dated) 24 x 18 in (60.96 x 45.72 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

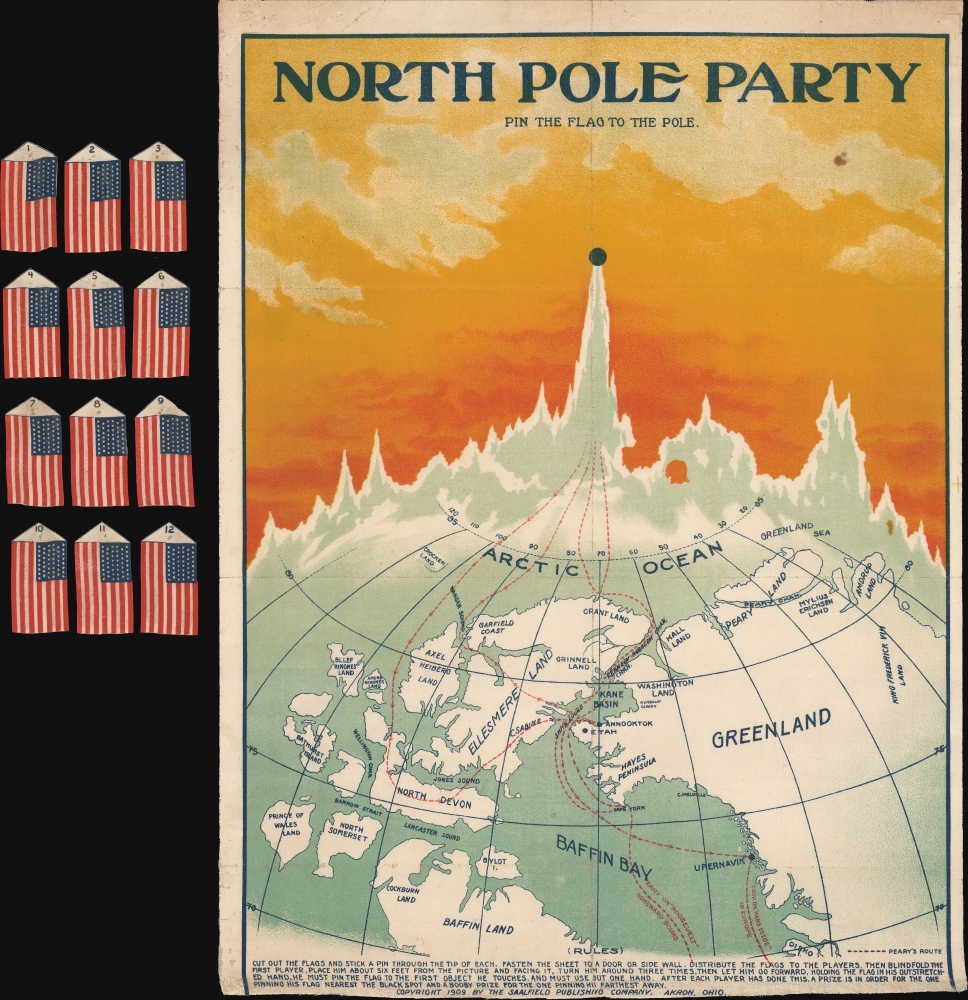

The map-game presents a stylized view of the northernmost part of the northern hemisphere, specifically northern Canada and Greenland, with landmasses, bodies of water, latitude, and longitude labeled. The island labeled Crocker Land at top-left was claimed to have been seen by Peary on an earlier expedition, but was subsequently shown not to exist, a fact proven by a dedicated 1913 expedition led by Donald Baxter MacMillan (1874 - 1970) a member of Peary's expedition that claimed to reach the North Pole in 1909. The outward and return routes of both Cook and Peary are traced, beginning with their known sea voyages, progressing via their purported treks over the ice, and ending at the North Pole.Gamplay follows a pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey scenario, in which the sheet of flags (all American, given Cook and Peary's nationality) accompanying the map were to be pinned on by blindfolded players, with those getting closest to the routes winning a prize and those furthest away receiving a booby prize. It capitalized on the widespread public interest, enthusiasm, international competition, and sheer chaos of the race to the North Pole.

Disputed Polar Discovery

This map is tied to a long-running, still-ongoing dispute about whether Frederick Albert Cook or Robert Peary was the first to reach the North Pole. Cook was a private adventurer, explorer, physician, and ethnographer who had been a member of an earlier, failed 1891-1892 Peary Expedition to reach the North Pole. He claimed to have led an expedition that reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. However, his voyage was poorly documented, and he was accompanied only by two Inuit guides, Ahpellah and Etukishook, both of whom gave conflicting reports. Peary, by contrast, was an American military man who had previously made several failed attempts to reach the North Pole. His fifth and final attempt began on July 6, 1908, when he and a team of 23 men set sail from New York Harbor. The expedition reached what they believed to be the North Pole on April 6, 1909, but on his return to New York, Peary discovered that Cook claimed to have already accomplished the feat several months earlier.Although Peary has historically been considered the first to reach the North Pole, Cook's claims were initially believed, and for a time, he was given credit for the achievement. It was only after the University of Copenhagen Commission and several other bodies (including the U.S. House's Naval Affairs Subcommittee), mostly stacked with Peary supporters, ruled in his favor that Peary's claim came to dominate. Cook's lack of documentary evidence and the conflicting accounts of his Inuit companions certainly did not bolster his case, nor did his disproven claim to have been the first to ascend Denali (Mt. McKinley) and his later conviction for fraud in promoting oil companies in the oil boom of the late 1910s and early 1920s. However, subsequent research has cast doubts on Peary's claims as well. The National Geographic Society and other Peary backers waged a campaign to promote his primacy that restricted access to the expedition's records. Peary kept much better records than Cook, but there were still gaps, incomplete data, or questionable claims that cast doubt on his assertion of having reached the pole.

In addition to scientific claims, the character of the two men, both of whom had strong incentives to inflate their achievements, has come into question. Cook's life contained a pattern of questionable behavior and fraudulent claims, but his comparatively respectful treatment of the Inuit has cast him in a more favorable light to posterity. For his part, Peary was open-minded with regard to race relations in the U.S., hiring Matthew Henson (1866 - 1955), an African-American man from Washington, D.C., as his right-hand man, first on a trip to Nicaragua to survey a potential canal route and then on his multiple Arctic expeditions. But he is now known to have behaved atrociously towards the Inuit, and not given either them or Henson their proper due for their role in his expeditions.

Historians, scientists, and polar explorers have attempted to recreate or otherwise test the claims of Cook and Peary, which has led to the majority view that both expeditions approached the North Pole without actually reaching it. In any event, the pole would not be definitively reached until May 12, 1926, when the airship Norge carrying Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen (the first to reach the South Pole) and others passed overhead. (American aviators Richard E. Byrd and Floyd Bennett claimed to have flown over it three days prior in an airplane, but these claims have been disputed.) A proven attainment of the pole on foot was not achieved until the late 1940s, when Soviet scientists who had flown in a plane that landed nearby stood on the pole. It was not until 1969 that a human verifiably reached the pole overland - Wally Herbert (60 years after Peary's claimed achievement).

Chromolithography

Chromolithography is a color lithographic technique developed in the mid-19th century. The process involved using multiple lithographic stones, one for each color, to yield a rich composite effect. Oftentimes, the process would start with a black basecoat upon which subsequent colors were layered. Some chromolithographs used 30 or more separate lithographic stones to achieve the desired effect. Chromolithograph color could also be effectively blended for even more dramatic results. The process became extremely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when it emerged as the dominant method of color printing. The vivid color chromolithography produced made it exceptionally effective for advertising and propaganda imagery.Publication History and Census

This map was prepared and printed (chromolithograph on linen) by the Saalfield Publishing Co. in 1909. Most likely, the flags were originally attached to the bottom of the sheet, but here they have been cut loose to facilitate gameplay; nonetheless, all 12 flags are present. The map is quite rare, only appearing once on the market in recent years and with only one known example (likely the same) in institutional collections, at the University of Southern Maine's Osher Map Library.Cartographer

Arthur J. Saalfield (April 1863 - January 11, 1919) founded the Saalfield Publishing Co. (1900 - 1977), a major publisher of children's books and other materials, including dictionaries and encyclopedias, based in Akron, Ohio. Born in Leeds, England, Saalfield and his family moved to the United States when he was a young boy. Settling first in New York City, Saalfield's father died shortly afterwards, and the family moved to Chicago. Arthur began working in the book trade at the age of nine, then moved to New York as a teenager to attend school, but quickly fell back into the book trade. He developed a reputation as a very effective salesman and quickly rose in the ranks of the industry. In 1892, he started his own bookselling business but left it in 1898 to run the trade book division of the Werner Company (founded in 1884 by Paul E. Werner, 1850-1931), based in Akron. Soon afterwards, Saalfield bought out the division from Werner; thus, the Saalfield Publishing Co. was a successor to Werner Company, though Werner continued to publish educational books afterwards occasionally. Werner's operation was already sizeable when Saalfield purchased it, and the latter wasted no time in ramping up production even further, moving several times to larger premises and churning out encyclopedias, novels (by the likes of Mark Twain, Horatio Alger, and Louisa May Alcott), and illustrated books of fairy tales. At its height, the company was one of the world's largest and most prominent publishers of children's books and games. Like many contemporary publishers, the company was bogged down in copyright litigation in the early 20th century, particularly with the Encyclopedia Britannica . Saalfield also began to experience health problems and was convalescing in Florida when he died in 1919. In 1885, he married the children's book author Adah Louise Sutton (1860 - 1935), and the couple had five children together. The eldest, Albert G. Saalfield (1886 - 1959), had worked with his father for several years and inherited management of the business. The Saalfield Publishing Co. continued to operate until 1977, after which its records were turned over to Kent State University. In 1987, the former company's large building in Akron burned down in a massive fire. More by this mapmaker...