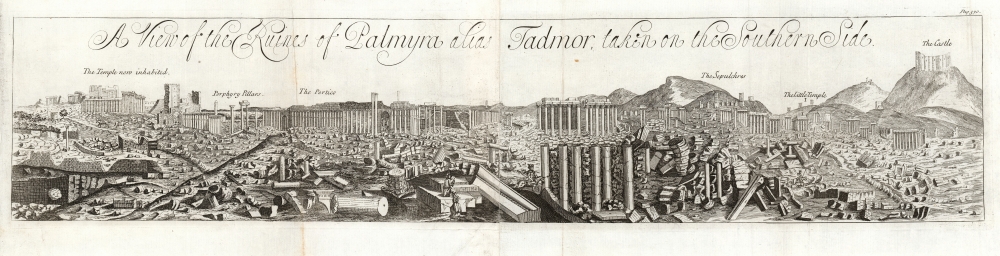

1695 / 1740 Gerard Hofstede van Essen Panorama of Palmyra, Syria

Palmyra-hofstede-1695

Title

1695 (undated) 6 x 28 in (15.24 x 71.12 cm)

Description

The Halifax Expedition

Hofstede accompanied the Halifax Expedition, which left Aleppo on September 29, 1691, arrived in Palmyra on October 4, and stayed until October 8: plenty of time for Hofstede to execute his drawings of the dramatic ruins. The composition is a sophisticated view - a panorama allowing the viewer to see specific prospects as if from one position, focusing on key architectural landmarks along the itinerary of the expedition. It presents a veritable forest of classical columns and ruins, bracketed by the Temple of Baal on the far left and the medieval fortress Qalaat Shirkuh on the right. The engraving is the first published view of Palmyra. Hofstede also executed a monumental, thirteen-foot-long painted version of the panorama, which he not only signed but also included a depiction of himself. The painting was commissioned by Gisbert Cuper, mayor of Deventer and a prominent Dutch intellectual. Hofstede painted the view in Aleppo and sent it to his patron in Amsterdam in 1693; the painting is now the property of the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam. Barring the great difference in scale, the content of the painting is identical to that of the present engraving, and it is plain that both are derived from the same drawings. This image was widely copied, providing the basis for all other views of the city until the middle of the 18th century.Attempts to Reach Palmyra

The 1691 expedition was the second European journey to Palmyra. A group of British merchants from the British Levant Company in Aleppo had spotted the rumored lost city of Palmyra in 1678 but were waylaid by the local Sheikh and sent back to Aleppo, shorn of their possessions. Two of the merchants on that expedition - Timothy Lanoy and Aaron Goodyear - later traveled with Halifax on the more successful 1691 expedition. Lanoy and Goodyear published an account of both journeys in the 1695 Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society; their account featured the engraving of Hofstede's view of the ruined city.A Storied City

Palmyra (Arabic: تَدْمُر Tadmur) possessed an ancient history dating to the early second millennium BCE, but by the 17th century it was practically unknown in the west. Palmyra does appear in glimpses on early maps; the 1660 Jansson map shows a 'Palmyrena.' It is probable that its appearance on any Western maps is derived from sources in the classical period, during which the city was a prosperous regional center, thriving as a caravan city with ties to the Silk Road. Palmyra was at its most powerful in the 260s CE following the Palmyrene King Odaenathus' defeat of Persian Emperor Shapur I (reign 240 - 270), and the king's succession by Queen Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the Palmyrene Empire. This did not work out well. In 273, Roman Emperor Aurelian (reign 270 - 275) reduced the city. Palmyra converted to Christianity during the 4th century and to Islam under the 7th-century Rashidun Caliphate. The city was reduced by the Timurids in 1400 to a small village, its monuments and temples all but forgotten. Travelers in Aleppo, however, described the ruins of the ancient metropolis surrounded by monumental tombs, attracting the attention of Western scholars and travelers. Lanoy and Goodyear's account, followed by Robert Wood's 1753 The Ruins of Palmyra, captured the attention of the learned public in both England and France, leading to an upsurge in classical art in both countries. The site remains an archaeological treasure despite widespread destruction related to the Syrian Civil War. Some of this destruction was deliberate: in an egregious 2015 assault on history, the temple of Baal, dedicated in 32 CE, was reduced to rubble by the Islamic State.Publication History and Census

Hofstede's view was first printed to accompany the Lanoy and Goodyear account published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Volume 19 Issue 218. It appeared again, unchanged barring the pagination, in Abednego Sellers' 1696 The Antiquities of Palmyra; Cornelis De Bruyn copied the detail from Hofstede's view for his own 1698 panorama of the ruins. The original plates were used again when Lanoy and Goodyear were reprinted in Miscellanea Curiosa (2nd ed. London: Smith, 1708). The plates were used yet again in An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time to the Present (Osborne, T. London) 1740-7. This example corresponds to those we have seen in that work. Despite the popularity of the topic and the long publishing history, we see no separate examples of this view cataloged in institutional collections.Cartographer

Gerard Hofstede van Essen (fl. 1690-1720) was a German/Dutch artist and traveler, active in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. He is only known by a handful of works attributed to him: views of Persepoli, Isfahan, and Naqsh-i Rustam in Iran; his c. 1713 'A Prospect of Constantinople;' his 1693 painted view of the newly-discovered ruins of Palmyra, and the printed view based on his own life-drawing of those ruins. Hofstede is understood to have accompanied William Halifax's 1691 expedition to Palmyra from Aleppo, where Hofstede was living at the time. More by this mapmaker...