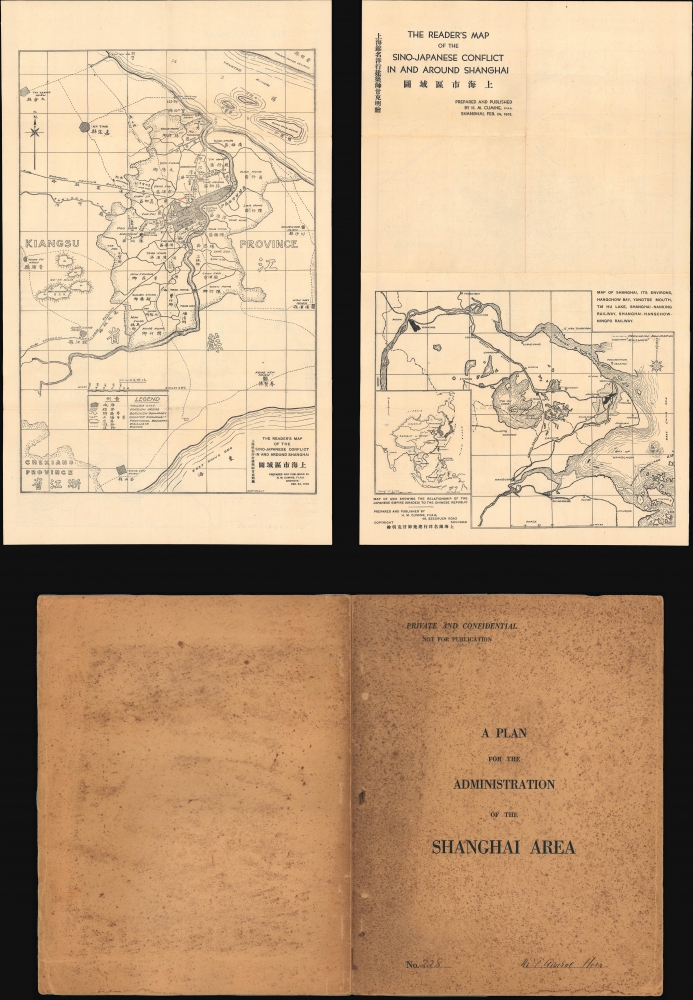

1932 Cumine Proposal for Demilitarized International Zone, Shanghai

ShanghaiPlan-cuminehm-1932

Title

1932 (dated) 20.75 x 14 in (52.705 x 35.56 cm) 1 : 165000

Description

A Closer Look

Presenting the city of Shanghai and its hinterland, from the Yangtse (Yangzi) River to the borders of Chekiang (Zhejiang) Province, this map notes administrative boundaries, roads, railways, waterways, hills, and other features, including communications stations, parks, county seats (hsien), and the 'Poo Sung Aerodrome,' today's Hongqiao International Airport. Produced during a brief but intense conflict between China and Japan, the map uses red overprint to highlight Chapei (Zhabei) District, where most of the fighting took place.Two additional maps appear on the verso, one depicting the wider region around Shanghai, including Nanking (Nanjing), Hangchow (Hangzhou), and Ningpo (Ningbo), emphasizing railways in particular. An inset at left presents East Asia, emphasizing the extent of the Japanese Empire and Republic of China.

A Plan for Peace

The accompanying plan booklet is a proposal, apparently unsolicited by either of the belligerents, to declare Greater Shanghai a demilitarized zone and establish a multinational administrative system. These aims were not purely idealistic since the International Settlement already maintained a multinational police force and had previously operated a 'Mixed Court' including Chinese officials to adjudicate disputes involving Chinese nationals. At the same time, the document reflects the attitudes of the multinational business community in Shanghai, who were usually able to overcome political disputes to pursue their common interests, rather than political leaders outside of Shanghai whose agreement would be necessary to enact such an agreement.In reality, the situation in Shanghai and throughout China was changing in a way that made such cooperation impossible. The increasingly powerful Chinese Nationalist government based in Nanjing was not about to surrender control of the Greater Shanghai Municipality, which it had spent the preceding years developing, largely as a precursor to an expected future return of the foreign concessions to Chinese sovereignty. The Japanese, including the Japanese business community, were also increasingly unwilling to compromise as their numbers and influence in China increased. To their minds, the old Anglo-American elite of Shanghai was conspiring to limit their growing interests in the city, leaving them to suffer the brunt of a Chinese anti-imperialist backlash. Regardless, Japan's civilian government was becoming increasingly ineffective in the face of intense nationalism, with the Japanese military forces occupying parts of China forming the core of ultranationalist secret societies looking to do away with civilian government altogether and push for further gains in China.

In the end, it is unclear if the plan (dated March 21), signed by 'An International Group of Shanghai Residents,' exerted any influence on the peace negotiations, but the ceasefire agreement signed on May 5 did follow the basic premise of demilitarizing the city outlined here.

An Esteemed Provenance

As the title page of the booklet indicates, this example of the administrative plan belonged to Admiral (Octave Benjamin) Herr (1873 - 1964), the commander of French military forces in Shanghai and simultaneously commander of the division navale d'Extrême-Orient. Herr had only recently been dispatched to Shanghai in an effort to assert the French government's authority in the French Concession, which was effectively under the control of the Shanghai Green Gang, an extremely powerful mafia that oversaw the city's opium, gambling, and prostitution industries. The relatively weak French concession authorities had entered into a pacte avec le diable with the Green Gang in order to manage the overwhelmingly Chinese population of the French Concession, including the 'handling' of troublesome labor disputes, and found itself at the gang's mercy.Against the backdrop of the 1932 Sino-Japanese Conflict, Herr moved to sideline the Green Gang by declaring martial law in the French Concession and banning opium and gambling. These actions set off a months-long battle for control of the French Concession, which saw a string of mysterious deaths of leading French officials, political maneuverings in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Paris, and a strike initiated by the Green Gang. In the end, the effort Herr kickstarted resulted in a partial, temporary reassertion of French control in the French Concession. For his part, Herr quickly moved on to other duties, serving as Inspecteur général des forces maritimes du Nord and a member of the Conseil supérieur de la Marine before the end of 1932.

The Shanghai Incident of 1932

The conflict of January 28th, 1932, also known as the Shanghai Incident, was a precursor to the Second Sino-Japanese War, which would begin five years later with an even more destructive battle for Shanghai. The roots of the 1932 conflict lie in increasingly aggressive Japanese imperialism, specifically the unprovoked and unauthorized invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 by the hypernationalist Kwantung Army (Kantōgun). The Chinese government was in a difficult position, as the country was disunified and relatively weak militarily; a full-scale conflict with Japan could prove disastrous, but popular anger against Japanese imperialism was intense and demanded a response.Against this background, a group of ultranationalist Nichiren monks provoking Chinese residents was attacked in Shanghai. In the following weeks, back-and-forth acts of violence were launched by provocateurs, and both sides began to reinforce their militaries. The situation was complicated by Shanghai's divided jurisdiction and multinational elite, who preferred making money to fighting wars. The foreign concessions were expected to be safe from any conflict, but fighting nevertheless spilled over into the Japanese-inhabited portion of the International Settlement (Hongkou or Hongkew).

Once fighting commenced on a large scale, the Chinese Nationalist troops performed better than expected, concentrating in Zhabei in order to protect the strategically important Shanghai Railway Station (North Station here), through which supplies and reinforcements could be readily delivered. Still, after weeks of intense fighting and failed negotiations, the better-armed and supplied Japanese troops began to make costly gains, convincing Chiang Kai-Shek and his commanders to pull back from the city. Japan was not in a position to pursue a full-scale war, thus both sides began to negotiate towards a ceasefire, which saw the immediate vicinity around Shanghai 'demilitarized,' though Japan was allowed to keep a garrison in its portion of the International Settlement.

In retrospect, the 1932 fighting was a preview of the even more intense battle for Shanghai in the autumn of 1937, which began the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was largely the same areas - Zhabei and Hongkou - which saw fighting and widespread destruction in both conflicts. The fighting in 1932 caused a surge of refugees into the relative safety of the foreign concessions, as would be the case on a larger scale in 1937. Even the course of the fighting followed a similar pattern, with Chinese troops' determination overcoming technological limitations but with them ultimately being driven away from the city by Japanese reinforcements. In the waning days of the 1932 conflict, the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo was established, but the Japanese government led by Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi refused to formally acknowledge it, a sign of the rift between the military and civilian government. On May 15, Inukai was assassinated by ultranationalist junior military officers, who were subsequently given a light sentence, eroding the rule of law and allowing the military to exert greater control over Japanese politics.

Shanghai in the Treaty Port Era

Although it was already a sizable port by 1842, Shanghai expanded at a tremendous pace when it was designated a treaty port after the First Opium War (1839 - 1842). British and French traders and missionaries were leased land outside of the walled 'Chinese City,' particularly along the waterfront that came to be known as the Bund, which housed numerous foreign and Chinese banks and trading houses, consulates, clubs, and high-end hotels and restaurants.Due to the extraterritoriality clauses of the Treaty of Nanjing and subsequent 'unequal treaties,' over time, the areas where Westerners resided effectively became exempt from Chinese jurisdiction. In 1862, the French split with the Americans and British, creating a distinct French Concession, causing the 'Anglos' to form the International Settlement (divided at Avenue Edward VII and Avenue Foch, today's Yan'an Road). As a strategically located entrepot near the mouth of the Yangzi River, Shanghai quickly became a gateway to the entire Yangzi Delta. The light administration of the foreign concessions led to the city's reputation for economic dynamism, multiculturalism, crime, drugs, prostitution, and urban poverty.

The British influence was particularly strong in the International Settlement, but the city's elite was a cosmopolitan mix of Europeans, Americans, Japanese, Chinese, and others. Trading diasporas from across China and the globe set up shop there, including Baghdadi Jews, whose names (Kadoorie, Sassoon) were synonymous with Shanghai's high society. Since the exact sovereign status of the treaty ports was unclear, Shanghai became a refuge for Chinese escaping the law or political repression, as well as stateless individuals and refugees, including White Russians and Viennese Jews fleeing the Nazis. Multiple nationalities also formed a subaltern stratum of police officers, servants, small business owners, and entertainers, including Parsis and Sikhs, Annamese, Koreans, Russians, Portuguese (Macanese), and Filipinos. However, the largest component of the city's population by far, including in the foreign concessions, were Chinese from near and far. Traders, absentee landowners, intellectuals, and professionals composed the Chinese elite and middle classes, while the city's working-class tended to be migrants from the nearby countryside or further north in Jiangsu Province (Subei).

Publication History and Census

These maps were prepared by Henry Monsel Cumine, a prominent architect and real estate developer, on February 24, 1932, in the midst of the conflict described above. As mentioned above, this example of the plan booklet was addressed to Admiral Octave Benjamin Herr, commander of French military forces in Shanghai. The maps are quite rare, being held by the National Library of Australia and the Virtual Shanghai project, while the plan booklet is not listed among any institutional collections.Cartographer

Henry Monsel Cumine (甘克明; July 7, 1882 - July 20, 1951) was a prominent Scottish-Chinese architect, real estate developer, cartographer, and newspaper publisher in Shanghai in the early 20th century. He was often erroneously referred to as Irish in contemporary documents, but his father was Scottish and his mother Chinese. Cumine and his wife Winifred Greaves (also Eurasian or mixed-race) had seven children, one of whom, Eric, also became a prominent architect himself and racing enthusiast discussed in James Carter's 2020 book Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai. Despite a strong affinity for his Scottish roots, H. M. Cumine was born in Shanghai and spoke Mandarin, Shanghainese, and Cantonese in addition to English, no doubt an asset in his business dealings. As a youth, he studied architecture in the offices of the Shanghai Municipal Council and worked on several public projects, as well as teaching at the Tong Shan Engineering and Mining College and working as an editor for an English-language newspaper in Hankow (now Wuhan). In 1901, at the age of 21, he founded the China Land and Building Company (上海錦名洋行), quickly establishing the company as one of the main architectural and real estate firms in the fast-growing city. He was soon considered a leading expert of the time on the complex land regulations of Shanghai. Cumine amassed a tremendous fortune and built an impressive 16-room mansion known as the Ferryhill House in the French Concession. Continuing his earlier experience with newspapers, Cumine bought the Shanghai Mercury, one of the main English dailies in Shanghai, in 1928. In 1938, he either launched or bought a recently-launched Chinese-language paper, the Wenhui bao (文匯報), known in English as The Standard. Created in the wake of Japan's occupation of the Chinese-administered parts of Shanghai, the paper quickly developed a reputation as a safe haven for patriotic Chinese writers to rail against the Japanese invaders. Cumine's involvement with the paper seems to have been short-lived, and over time it became a leading left-wing paper aligned with the Chinese Communist Party, acting as their 'voice' in Hong Kong, especially in the years before the 1997 handover of sovereignty. In any event, Cumine was not poised to do well financially or politically under Japanese occupation and his family relocated to Hong Kong during the Second Sino-Japanese War. More by this mapmaker...