1962 Peking Review Set of Maps on the Sino-Indian War

SinoIndianWar-pekingreview-1962$1,000.00

Title

Peking Review 47 and 48, Sino-Indian Border Dispute.

1962 (dated) 11.5 x 15.75 in (29.21 x 40.005 cm) 1 : 2534400

1962 (dated) 11.5 x 15.75 in (29.21 x 40.005 cm) 1 : 2534400

Description

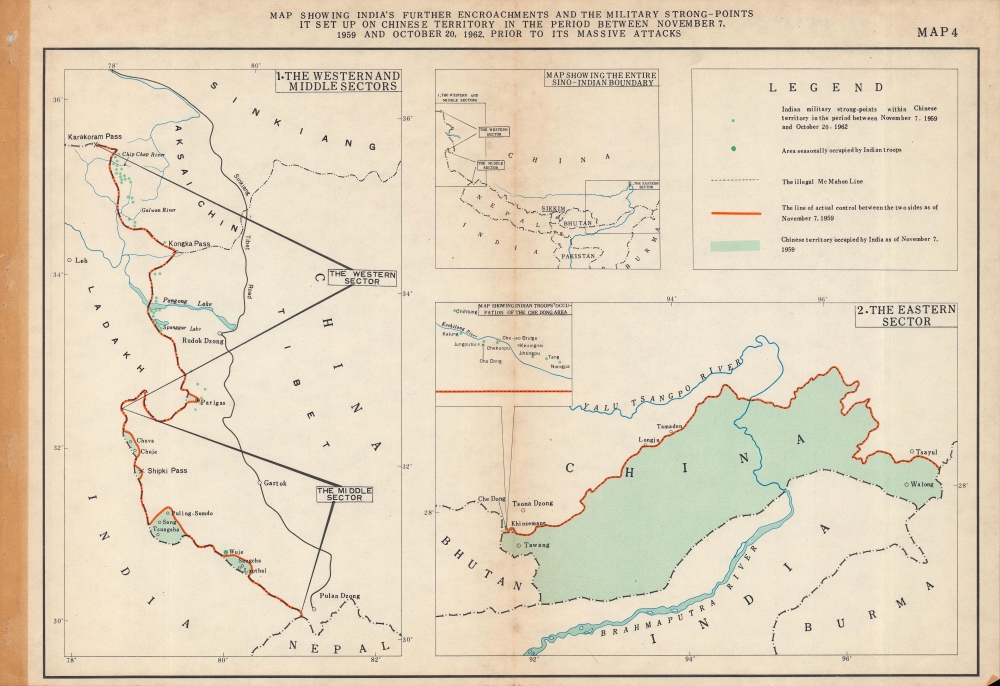

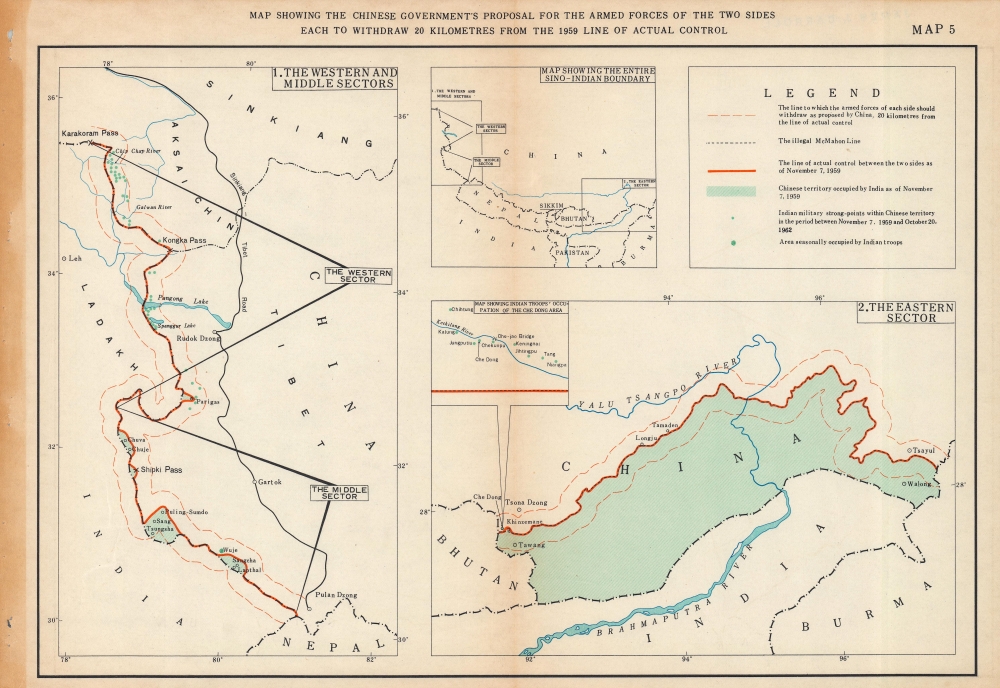

An extensive 1962 set of historical maps of the Sino-Indian border, published in the Peking Review, an English-language periodical tied to the Chinese Communist Part. They represent a rarely-seen Chinese perspective on a little-known but significant episode in the Cold War. The focus is the Sino-Indian War, a border conflict fought at extreme elevations. The war soured relations between Russia and China, the world's largest nations and heralded the Sino-Soviet Split.

The large but mostly uninhabited region of Aksai Chin posed a special problem. The Qing had considered the area part of its territory (Xiyu, 'Western Regions'), but a large-scale revolt in the 1860s - 1870s expelled the Qing, leading the British to negotiate with the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, who also claimed the territory. However, after reclaiming the Western Regions (now renamed Xinjiang) in the 1890s, the Qing constructed border posts in Aksai Chin.

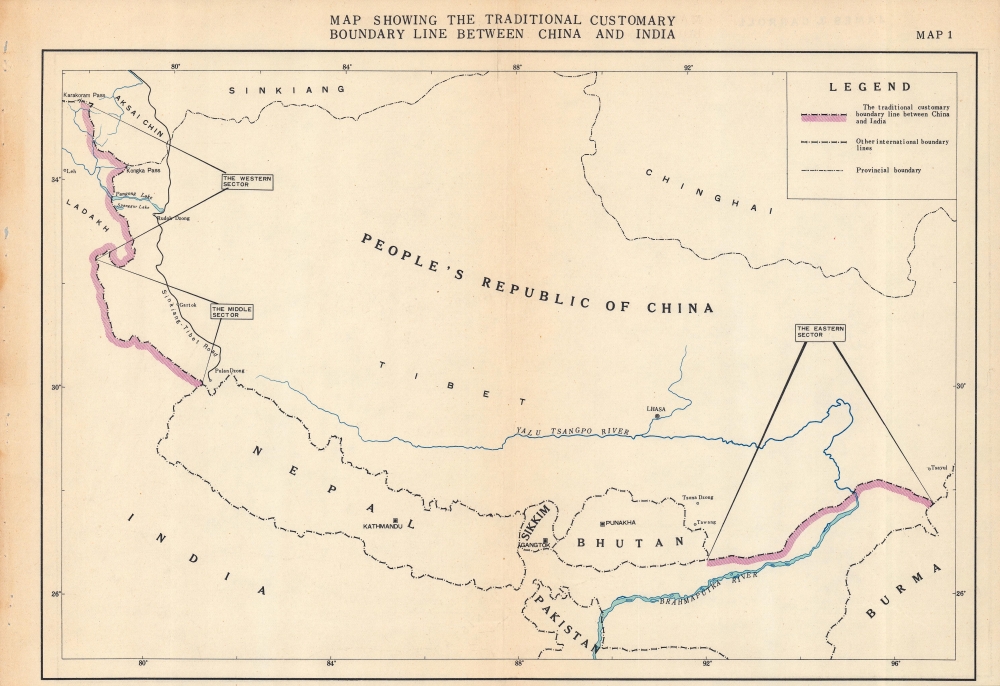

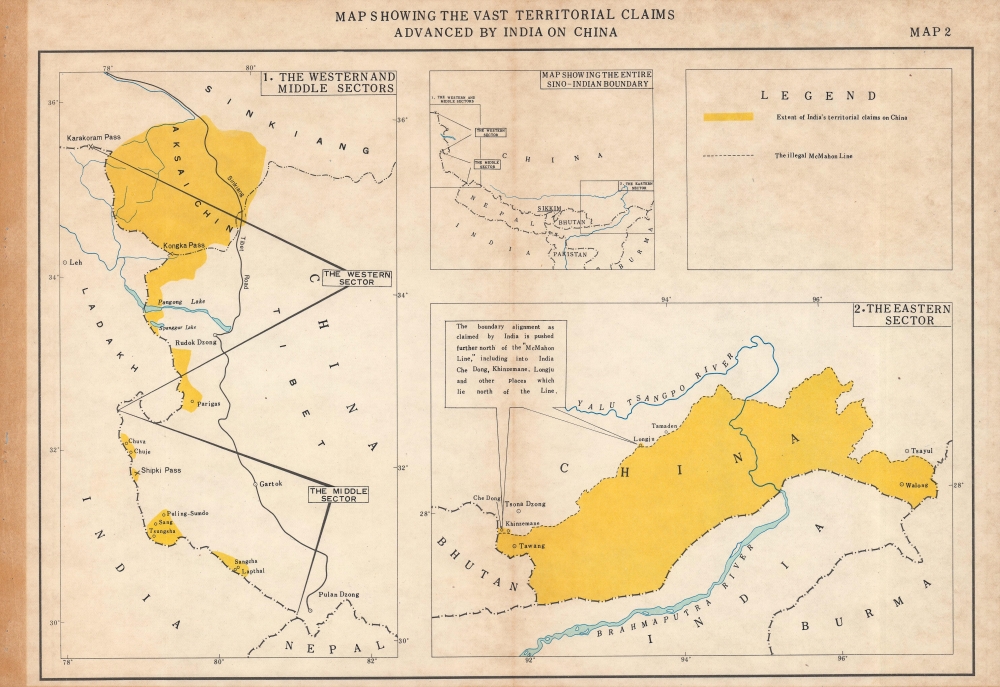

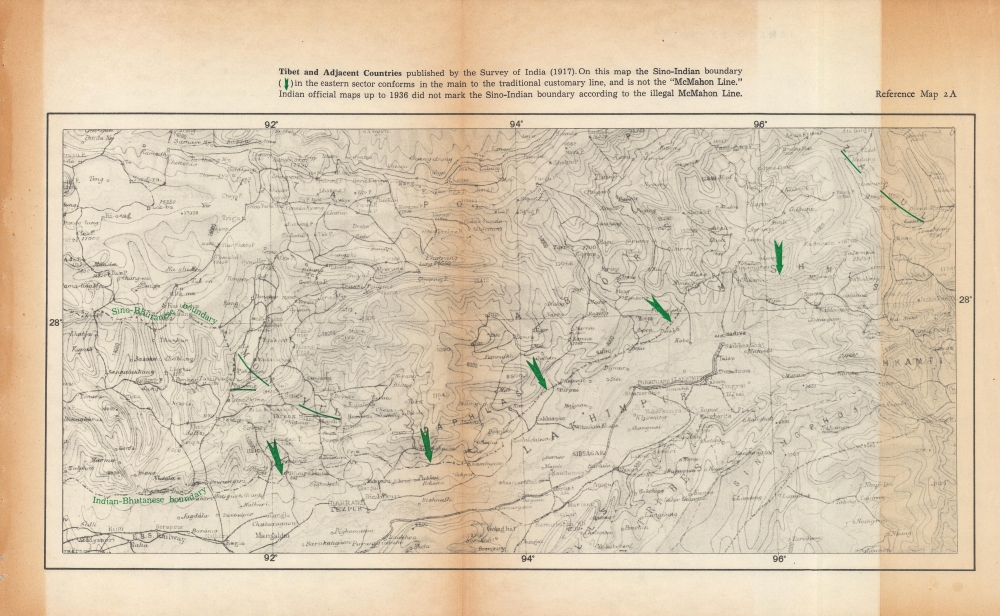

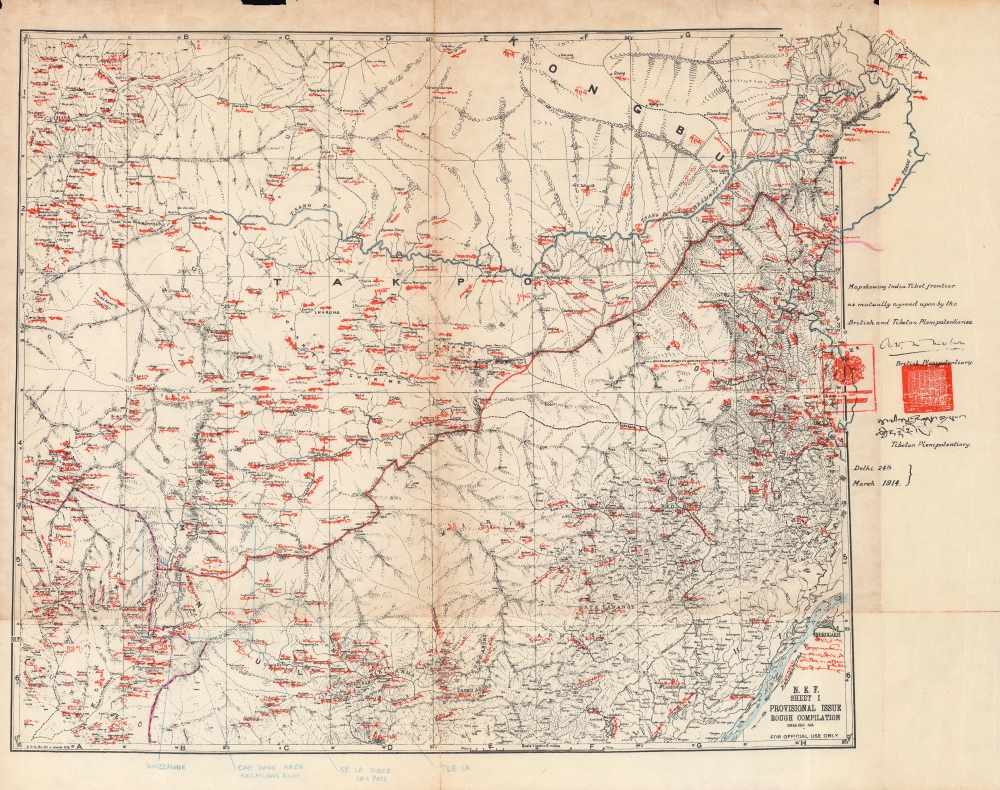

Throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, various proposals were made to demarcate a border, but growing British interest in Tibet (including a de facto invasion in 1903 - 1904) and the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 left the dispute unresolved. With Tibet effectively independent at this point, the British and the Dalai Lama government settled on a border (known as the McMahon Line) in the Simla Convention of 1914. However, even this agreement left many ambiguities, and, as the Chinese government was not party to the negotiations, it has never accepted this as the border (it is referred to here as 'the illegal McMahon Line').

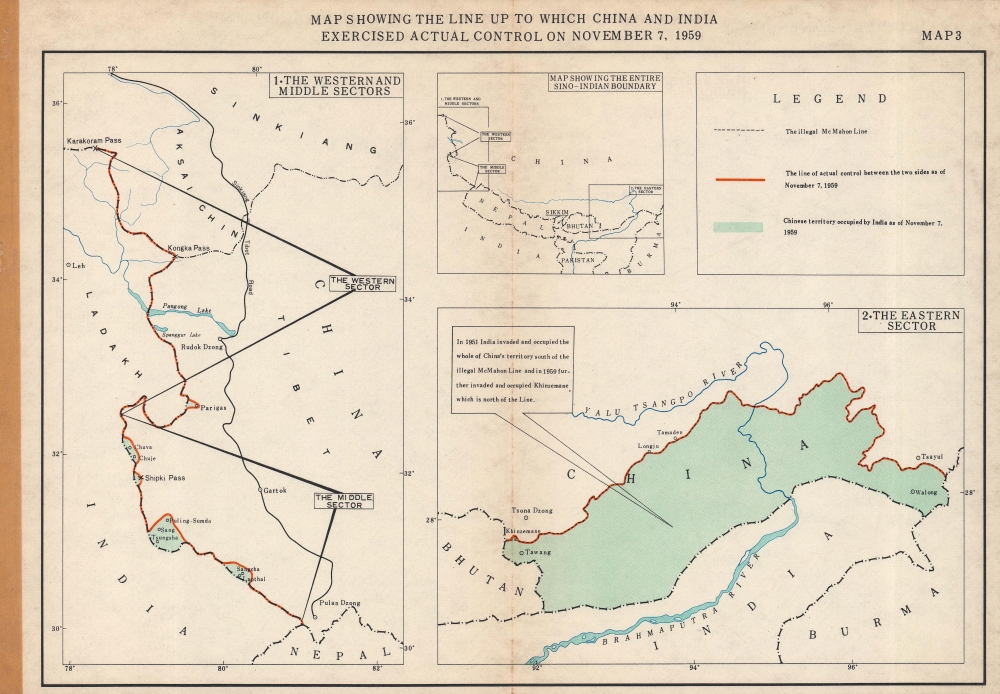

In 1961, China began patrolling and setting up border posts in the disputed territory, though, as referenced here, Indian troops also occasionally operated within the disputed territory as well. In the spring of 1962, border clashes erupted, and negotiations failed to resolve the issue. Finally, on October 20, China launched a full-scale advance into the disputed territory along the 'line of actual control,' the de facto border. While Chinese forces enjoyed success in pushing Indian troops back in Aksai Chin, international attention was turning towards the conflict and China was increasingly isolated. Aside from some portions of Aksai Chin, Chinese troops retreated to the 'line of actual control,' having 'made a point' but leaving the dispute unresolved ever since.

In the minds of Chinese leaders, Aksai Chin and other disputed border regions were already Chinese territory and Indian troops were provocatively entering it, thus justifying retaliation (they also appear to have seen their attack as preemptive, wrongly expecting a major Indian offensive). Also, most historians outside of China believe that Mao started the war to test the Sino-Soviet relationship. In response to the conflict, not only did the Soviets stay neutral, but they even offered military aid to India, reflecting their view that China was being aggressive and unreasonable. This reinforced Mao's conviction that the Soviets were insufficiently revolutionary, lacked the will for struggle, and that he, not Khrushchev, should be the leader of global Communism. The war was an important factor in deepening the Sino-Soviet Split and redirecting the Cold War. The border dispute, however, has long outlived the Cold War, and has intensified in recent years, with lethal clashes between Chinese and Indian troops.

A Closer Look

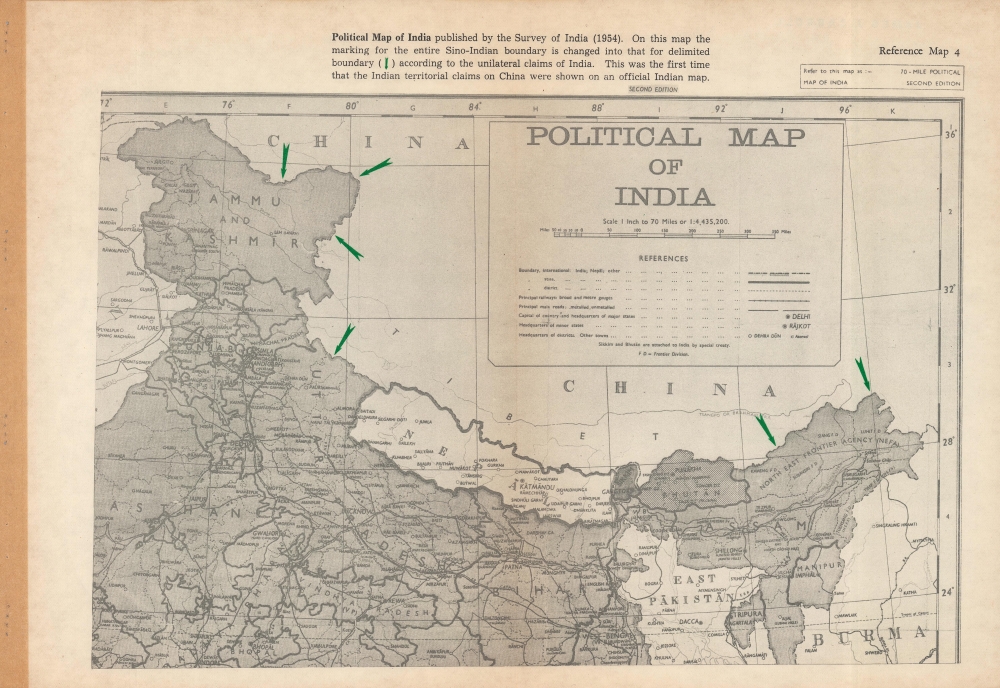

Thirteen maps are included in total, combining five produced by the Peking Review and six older maps (two of them in two parts) republished for reference. The Peking Review maps give a general overview of the situation from a Chinese perspective, dividing the frontier between the two countries into western (Ladakh, in Jammu and Kashmir), middle (Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh), and eastern (North-East Frontier Agency) sectors. Together, these maps are meant to reinforce the Chinese view that India occupied disputed territory rather suddenly and without provocation, necessitating a Chinese response.Origins of the Border Dispute

The origins of the Sino-Indian border dispute lie in the 19th century, as notions of strict territorial sovereignty were introduced as first the Sikh Empire and then the British expanded their reach at the expense of local states and in the context of a weakened Qing China. Initially, both the British and Chinese agreed to maintain traditional methods of border demarcation, using rivers, mountains, and other natural features. But these methods were vague and incomplete, so that over the course of the 19th century, the British sought a more precisely demarcated border, especially in very remote areas.The large but mostly uninhabited region of Aksai Chin posed a special problem. The Qing had considered the area part of its territory (Xiyu, 'Western Regions'), but a large-scale revolt in the 1860s - 1870s expelled the Qing, leading the British to negotiate with the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, who also claimed the territory. However, after reclaiming the Western Regions (now renamed Xinjiang) in the 1890s, the Qing constructed border posts in Aksai Chin.

Throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, various proposals were made to demarcate a border, but growing British interest in Tibet (including a de facto invasion in 1903 - 1904) and the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912 left the dispute unresolved. With Tibet effectively independent at this point, the British and the Dalai Lama government settled on a border (known as the McMahon Line) in the Simla Convention of 1914. However, even this agreement left many ambiguities, and, as the Chinese government was not party to the negotiations, it has never accepted this as the border (it is referred to here as 'the illegal McMahon Line').

The Sino-Indian War

In the autumn of 1962, while the world was focused on Cuba and the potential of a nuclear war breaking out, a 'hot war' was taking place on the other side of the world that also held great significance for the future course of the Cold War. Although India and Communist China enjoyed friendly relations at first, China's occupation of Tibet and gradual extension of its rule there set the stage for newly intense border disputes. These were given added impetus with uprisings throughout Tibet in the late 1950s and the flight of the Dalai Lama to India. Additionally, China's relationship with the Soviet Union was beginning to deteriorate (the Sino-Soviet Split), while Soviet-Indian relations were improving, and the People's Republic feared an India holding solid relations with both the U.S. and the Soviet Union. India and China were also vying for pre-eminent status among the non-Western, newly decolonized, and non-aligned countries of the world (which is why Zhou Enlai wrote a letter to Asian and African leaders, included along with the maps in this issue of Peking Review).In 1961, China began patrolling and setting up border posts in the disputed territory, though, as referenced here, Indian troops also occasionally operated within the disputed territory as well. In the spring of 1962, border clashes erupted, and negotiations failed to resolve the issue. Finally, on October 20, China launched a full-scale advance into the disputed territory along the 'line of actual control,' the de facto border. While Chinese forces enjoyed success in pushing Indian troops back in Aksai Chin, international attention was turning towards the conflict and China was increasingly isolated. Aside from some portions of Aksai Chin, Chinese troops retreated to the 'line of actual control,' having 'made a point' but leaving the dispute unresolved ever since.

In the minds of Chinese leaders, Aksai Chin and other disputed border regions were already Chinese territory and Indian troops were provocatively entering it, thus justifying retaliation (they also appear to have seen their attack as preemptive, wrongly expecting a major Indian offensive). Also, most historians outside of China believe that Mao started the war to test the Sino-Soviet relationship. In response to the conflict, not only did the Soviets stay neutral, but they even offered military aid to India, reflecting their view that China was being aggressive and unreasonable. This reinforced Mao's conviction that the Soviets were insufficiently revolutionary, lacked the will for struggle, and that he, not Khrushchev, should be the leader of global Communism. The war was an important factor in deepening the Sino-Soviet Split and redirecting the Cold War. The border dispute, however, has long outlived the Cold War, and has intensified in recent years, with lethal clashes between Chinese and Indian troops.

Publication History and Census

These maps were published in the Peking Review in November 1962 in a special issue on the Sino-Indian border conflict. This issue is independently cataloged in the OCLC but without any institutional collections.Condition

Very good. Original fold lines visible, stitching in margins, some defined discoloration in margins on some maps.

References

OCLC 56523139.