This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

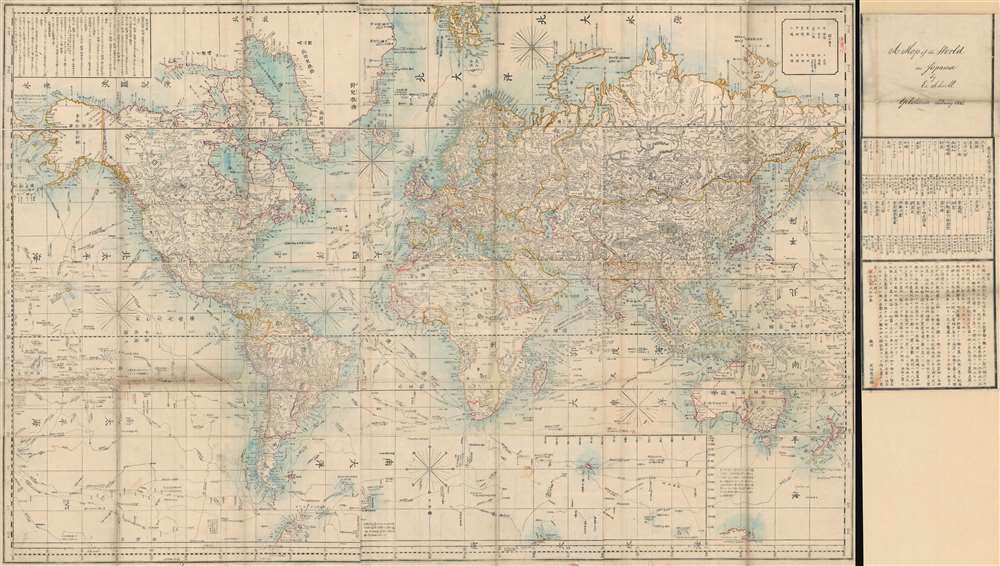

1862 Schnell and Takeda Map of the World (in Japanese)

World-schnell-1862$2,000.00

Title

Bankoku Kōkai-zu / 萬国航海圖 / World Navigational Map.

1862 (dated) 35.5 x 63 in (90.17 x 160.02 cm) 1 : 26000000

1862 (dated) 35.5 x 63 in (90.17 x 160.02 cm) 1 : 26000000

Description

This is a remarkable 1862 Yokohama Published Japanese large format Japanese map of the world by Edward Schnell and Kango Takeda. This map is based upon an English map drawn by John Purdy and others in 1845. Kango Takeda published a Japanese version of the chart in 1858. The map details the world with numerous Japanese notes and annotations, including the routes of prominent explorers.

The present example is an updated version of the Kango Takeda publication revised by the Dutch/German arms dealer Edward Schnell - whose name appears in the title. The title section, usually appended to the map proper, has been detached in this particular case, most likely during an earlier restoration process. The same can be easily re-attached to the map proper, if required.

The OCLC notes only 1 example in the Library of Congress. A second example is held in the East Asian Library at U.C. Berkeley. We have no doubt this map has a fascinating story, which we will attempt to unearth in the coming weeks.

The present example is an updated version of the Kango Takeda publication revised by the Dutch/German arms dealer Edward Schnell - whose name appears in the title. The title section, usually appended to the map proper, has been detached in this particular case, most likely during an earlier restoration process. The same can be easily re-attached to the map proper, if required.

The OCLC notes only 1 example in the Library of Congress. A second example is held in the East Asian Library at U.C. Berkeley. We have no doubt this map has a fascinating story, which we will attempt to unearth in the coming weeks.

Condition

Very good. Some loss over fold intersections. Minor worm holes. Some wear and foxing along original fold lines. Minor spotting at places. Professionally flattened and backed with archival tissue. The title is usually appended to the right of the map, but in this case is detached. Can be reattached easily.

References

OCLC 5569126. Univ. of California Library, Berkeley, East Asian Library, A14.