This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

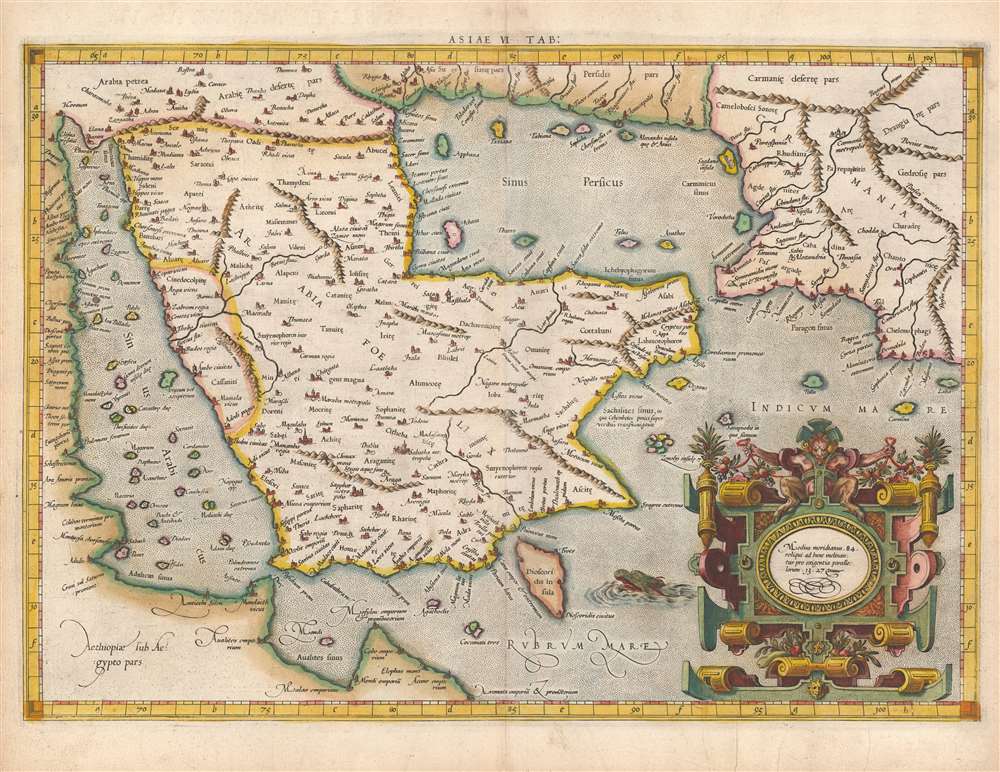

1584 Mercator Map of Arabia Based on Ptolemy

Arabia-mercatorptolemy-1584

Title

1584 (undated) 13 x 18.5 in (33.02 x 46.99 cm) 1 : 9150000

Description

Exceeding all Previous Works

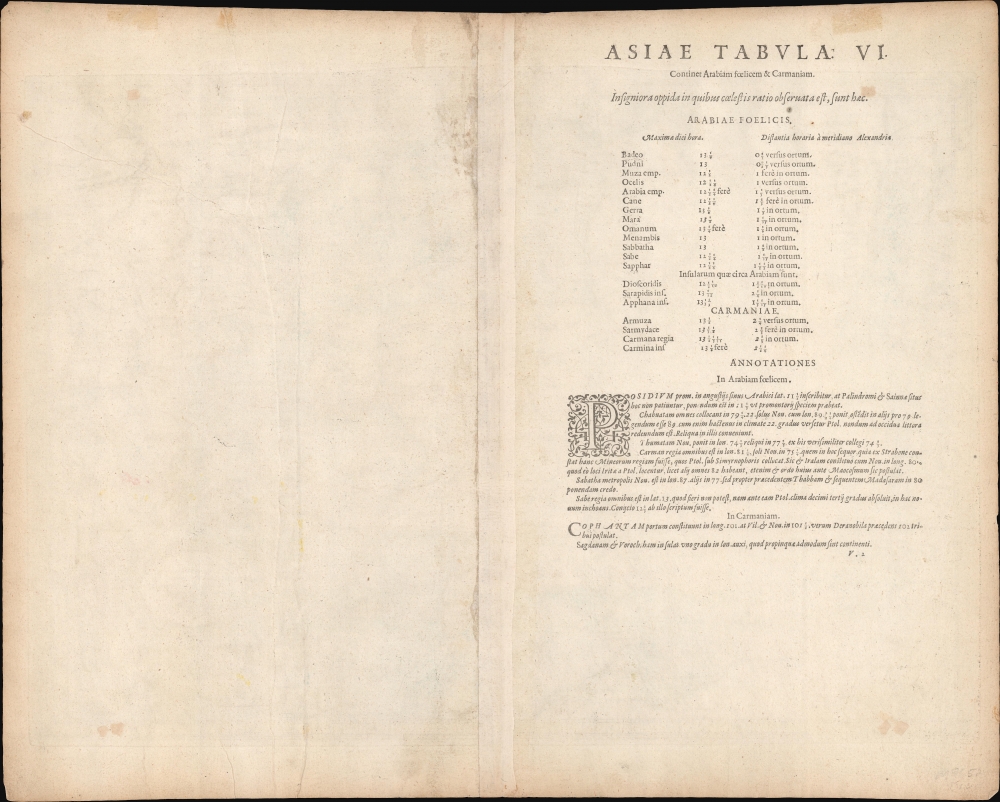

Previous editions, both copperplate and woodcut, had been comparatively crude renditions that often omitted detail and were prone to ambiguities. Mercator produced his versions of Ptolemy's maps using the latest engraving techniques, surpassed any that came before. 'This map is much more finely engraved and more accurately fitted to the tables, than any of the maps of the previous Ptolemy editions.' (Tibbetts, Arabia) Mercator's maps were more beautifully presented than any earlier Ptolemy, but his own innovations in the use of italic fonts allowed for the legible inclusion of more detail than prior iterations. (Mercator had in 1540 produced the first instructional handbook on the use of italics to appear outside Italy, and Mercator was the first engraver to use the typeface on a map.) Mercator had also edited and re-drafted the maps, consulting many printed and manuscript editions of Geographia in order to present as clear a rendition of Ptolemy's original design as possible. On the other hand, Mercator presented Ptolemy's maps on modern projections, dispensing with the crude trapezoidal projections employed in most earlier editions.The Cartographic Detail

The map's detail derives from the knowledge available in Alexandria in the second century, thus the place names change dramatically. The map does mention several places in present-day Qatar (Abucei, Leaniti, Themi, Asateni, and Aegei). Names added to this edition of the map include Mesmites Sinus, Idicar, and Iuicara, located in present-day Kuwait. The island of 'Ichara' appears: this is now understood to be the island of Kharj. The peninsula 'Chersonesi Extrema,' is believed to correspond to Ras Rakan ( رأس راكان) in present-day Qatar. Other notes point out details such as famous shrines, and Ichtyophagorium Sinus (the strait of the fish-eaters).The Importance of Ancient Geography

European exploration in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century had resulted in a massive expansion to their known world, far superseding Ptolemy's second-century geographical knowledge. And yet, mapmakers continued to publish editions of Ptolemy - often simultaneously with modern maps reflecting the new discoveries. The reason for this was that despite his antiquated data, Ptolemy's methodology remained essential and authoritative. By employing his great innovation - laying out a grid, and assigning to real-world locations coordinates - one could produce a mathematical representation of the world showing clearly the distances between known features. Every geographer of the Age of Discovery embraced Ptolemy's methodologies to absorb new discoveries. Any geographer, before developing new work, needed to understand the Ptolemaic foundations of their discipline and as a consequence, editions of Ptolemy would continue to be printed well into the eighteenth century.Publication History and Census

Mercator produced the first edition of his Ptolemy in Duisberg in 1578, as well as a second edition printed in Cologne from the same plates in 1584. The plates later passed to Jodocus Hondius, his successor, who issued editions in the early 17th century. In 1694, the plates were sold at auction to François Halma (1653 - 1722) who reworked them and published editions in 1695, 1698, and 1704. A final edition, from which this map came, was published in 1730 by R. and J. Wetstein and G. Smith. Some twenty examples of the 1584 Ptolemy are cataloged in institutional collections. The separate map appears in several institutions in its 1578 edition, but only the Biblioteca Nacional de España shows a copy of this map in the 1584 edition.CartographerS

Gerard Mercator (March 5, 1512 - December 2, 1594) is a seminal figure in the history of cartography. Mercator was born near Antwerp as Gerard de Cremere in Rupelmonde. He studied Latin, mathematics, and religion in Rupelmonde before his Uncle, Gisbert, a priest, arranged for him to be sent to Hertogenbosch to study under the Brothers of the Common Life. There he was taught by the celebrated Dutch humanist Georgius Macropedius (Joris van Lanckvelt; April 1487 - July 1558). It was there that he changed him name, adapting the Latin term for 'Merchant', that is 'Mercator'. He went on to study at the University of Louvain. After some time, he left Louvain to travel extensively, but returned in 1534 to study mathematics under Gemma Frisius (1508 - 1555). He produced his first world map in 1538 - notable as being the first to represent North America stretching from the Arctic to the southern polar regions. This impressive work earned him the patronage of the Emperor Charles V, for whom along with Van der Heyden and Gemma Frisius, he constructed a terrestrial globe. He then produced an important 1541 globe - the first to offer rhumb lines. Despite growing fame and imperial patronage, Mercator was accused of heresy and in 1552. His accusations were partially due to his Protestant faith, and partly due to his travels, which aroused suspicion. After being released from prison with the support of the University of Louvain, he resumed his cartographic work. It was during this period that he became a close fried to English polymath John Dee (1527 - 1609), who arrived in Louvain in 1548, and with whom Mercator maintained a lifelong correspondence. In 1552, Mercator set himself up as a cartographer in Duisburg and began work on his revised edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. He also taught mathematics in Duisburg from 1559 to 1562. In 1564, he became the Court Cosmographer to Duke Wilhelm of Cleve. During this period, he began to perfect the novel projection for which he is best remembered. The 'Mercator Projection' was first used in 1569 for a massive world map on 18 sheets. On May 5, 1590 Mercator had a stroke which left him paralyzed on his left side. He slowly recovered but suffered frustration at his inability to continue making maps. By 1592, he recovered enough that he was able to work again but by that time he was losing his vision. He had a second stroke near the end of 1593, after which he briefly lost speech. He recovered some power of speech before a third stroke marked his end. Following Mercator's death his descendants, particularly his youngest son Rumold (1541 - December 31, 1599) completed many of his maps and in 1595, published his Atlas. Nonetheless, lacking their father's drive and genius, the firm but languished under heavy competition from Abraham Ortelius. It was not until Mercator's plates were purchased and republished (Mercator / Hondius) by Henricus Hondius II (1597 - 1651) and Jan Jansson (1588 - 1664) that his position as the preeminent cartographer of the age was re-established. More by this mapmaker...

Claudius Ptolemy (83 - 161 AD) is considered to be the father of cartography. A native of Alexandria living at the height of the Roman Empire, Ptolemy was renowned as a student of Astronomy and Geography. His work as an astronomer, as published in his Almagest, held considerable influence over western thought until Isaac Newton. His cartographic influence remains to this day. Ptolemy was the first to introduce projection techniques and to publish an atlas, the Geographiae. Ptolemy based his geographical and historical information on the "Geographiae" of Strabo, the cartographic materials assembled by Marinus of Tyre, and contemporary accounts provided by the many traders and navigators passing through Alexandria. Ptolemy's Geographiae was a groundbreaking achievement far in advance of any known pre-existent cartography, not for any accuracy in its data, but in his method. His projection of a conic portion of the globe on a grid, and his meticulous tabulation of the known cities and geographical features of his world, allowed scholars for the first time to produce a mathematical model of the world's surface. In this, Ptolemy's work provided the foundation for all mapmaking to follow. His errors in the estimation of the size of the globe (more than twenty percent too small) resulted in Columbus's fateful expedition to India in 1492.

Ptolemy's text was lost to Western Europe in the middle ages, but survived in the Arab world and was passed along to the Greek world. Although the original text almost certainly did not include maps, the instructions contained in the text of Ptolemy's Geographiae allowed the execution of such maps. When vellum and paper books became available, manuscript examples of Ptolemy began to include maps. The earliest known manuscript Geographias survive from the fourteenth century; of Ptolemies that have come down to us today are based upon the manuscript editions produced in the mid 15th century by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus, who provided the basis for all but one of the printed fifteenth century editions of the work. Learn More...