This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1707 J. B. Homann Solar System on the Copernican Model

CopernicusSystem-homann-1707

Title

1707 (undated) 19 x 22.25 in (48.26 x 56.515 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

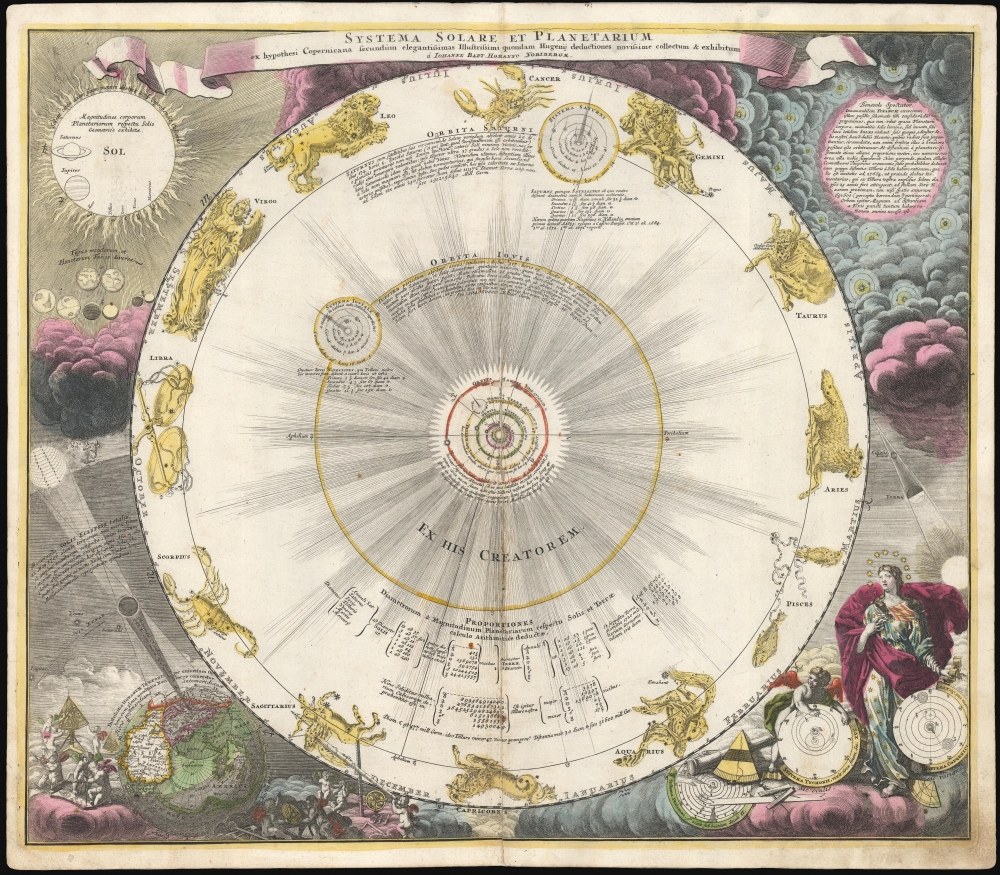

This celestial chart couches a scientific-revolution-era model of the solar system, and the calculations to measure it, in a baroque decorative framework. The sun is at the center, with the planets orbiting around it; both Jupiter and Saturn command the largest orbits, and appear with their moons (those that had been discovered.) Tables supply Huygens' calculations of the sizes and periods of the planetary orbits. Beyond Saturn's orbit, the constellations of the Zodiac represent the fixed stars of the firmament.An Array of Allegorical and Scientific Embellishment

In the lower right are three models of the solar system, including a visual commentary on their validity. These are the models of Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, and Copernicus: the disc of the Ptolemaic (geocentric) model lies buried beneath astronomical instruments, and is visibly broken. Tycho Brahe's is presented by a thoughtful putto. Third in line, the Copernican model (by this time the accepted, dominant model) is shown, presented by the regal Urania, goddess of astronomy - signified by her halo of stars, her star-studded gown, and her cloak embellished with zodiacal symbols. Between the shattered Ptolemaic system and the imperious, confident imprimatur Urania bestows on the Copernican, there is little doubt which of these systems is considered superior.To the lower left, a diagram of a solar eclipse is surrounded by a horde (constellation?) of putti astronomers clamoring about telescopes, massive sextants, and other astronomical instruments, in order to measure the phenomenon. The diagram depicts not just any eclipse, but the very recent one so eagerly measured by European scientists on May 12, 1706, and indicates, on the surface of the globe, the parts of Europe from which the event had been observed.

The diagram at upper left, showing the relative sizes of the sun and the planets, is a more attractively-rendered iteration of the same diagram first appearing in Huygens' work: the sun's fiery orb dwarfing the planets, especially the planets of the inner solar system. These are shown again, but larger, in order to illustrate their appearance in telescopes - with the exception of Earth, which is presented as both hemispheres of the globe. (The sharp-eyed reader will note that the western hemisphere features California-as-an-island.)

Other Worlds?

The clouds to the upper right contain the charts's most amazing revelation, again based on Huygen's speculation: an array of stars, each with their own orbiting planets. The Latin text, here paraphrased, explains:Kindly Observe: We present for your consideration the innumerable host of fixed stars, in this little diagram: which, not like the dark bodies of the planets, radiate the light innate to them as many suns. Doubtless they are surrounded by planets to which they impart their light, for we do not think they were placed there by the Creator in vain.(We remind the reader that this was printed in 1707, and that the first definitive evidence of a planet not orbiting our own sun would not be found until Michael Mayor and Didier Queloz' detection of an exoplanet orbiting 51 Pegasi on October 6, 1995.)

While Huygens had gone as far as speculating on the existence of extraterrestrial life, Homann does not explicitly take that next logical step. But he does assure the reader that such thorny philosophical and theological problems are made remote by sharing Huygens' observation on interstellar distances:

Huygens has deduced… that a cannonball fired from our planet, which would reach the sun after almost 25 years, would reach the nearest fixed star Sirius only after a space of 691,600 years (a horrible perception!)

Homann's Chart

The later appearance of this chart in the 1742 production of Johann Doppelmayr's Atlas Coelistis has led more than one cataloger to attribute this work to him. It would not be unreasonable to assume a connection: Homann and Doppelmayr did collaborate on a number of charts and maps as early as the first decade of the 18th century. However, in 1707 Doppelmayr published a pamphlet (Ausführliche Erklärung uber zwey neue Homännische Charten) which explained in detail both this chart and Homann's map showing the 1706 eclipse's path across Europe. In this work, Doppelmayr specifically refers to both of these as Homann's work, and not his own, so it is reasonable that we should take his word on the matter.Publication History and Census

This is the first plate of this celestial, engraved for Johann Baptist Homann in 1707 for inclusion in his planned Neuer Atlas. We are aware of at least two further states of this plate, exhibiting various degrees of re-working. Those include an Imperial privilege in the title, probably not Johann's but that of his son Johnann Christian, probably dating to 1726. The present example is from a 1710 edition of the Neuer Atlas. A later state, bearing the plate number 2 in the upper right, was included by Homann Heirs in Doppelmayr's Atlas Coelistis. They appear to have engraved an entirely new plate at some point thereafter, as late as the 1770s. In its various editions, the map is well represented in institutional collections and versions of the map appear on the market, but there is no complete census of individual states and plates, so the dating of these pieces is difficult to determine.Cartographer

Johann Baptist Homann (March 20, 1664 - July 1, 1724) was the most prominent and prolific map publisher of the 18th century. Homann was born in Oberkammlach, a small town near Kammlach, Bavaria, Germany. As a young man, Homann studied in a Jesuit school and nursed ambitions of becoming a Dominican priest. Nonetheless, he converted to Protestantism in 1687, when he was 23. It is not clear where he mastered engraving, but we believe it may have been in Amsterdam. Homann's earliest work we have identified is about 1689, and already exhibits a high degree of mastery. Around 1691, Homann moved to Nuremberg and registered as a notary. By this time, he was already making maps, and very good ones at that. He produced a map of the environs of Nürnberg in 1691/92, which suggests he was already a master engraver. Around 1693, Homann briefly relocated to Vienna, where he lived and studied printing and copper plate engraving until 1695. Until 1702, he worked in Nuremberg in the map trade under Jacob von Sandrart (1630 - 1708) and then David Funck (1642 - 1709). Afterward, he returned to Nuremberg, where, in 1702, he founded the commercial publishing firm that would bear his name. In the next five years, Homann produced hundreds of maps and developed a distinctive style characterized by heavy, detailed engraving, elaborate allegorical cartouche work, and vivid hand color. Due to the lower cost of printing in Germany, the Homann firm could undercut the dominant French and Dutch publishing houses while matching their diversity and quality. Despite copious output, Homann did not release his first major atlas until the 33-map Neuer Atlas of 1707, followed by a 60-map edition of 1710. By 1715, Homann's rising star caught the attention of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, who appointed him Imperial Cartographer. In the same year, he was also appointed a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Homann's prestigious title came with several significant advantages, including access to the most up-to-date cartographic information as well as the 'Privilege'. The Privilege was a type of early copyright offered to very few by the Holy Roman Emperor. Though less sophisticated than modern copyright legislation, the Privilege offered limited protection for several years. Most all J. B. Homann maps printed between 1715 and 1730 bear the inscription 'Cum Priviligio' or some variation. Following Homann's death in 1724, the firm's map plates and management passed to his son, Johann Christoph Homann (1703 - 1730). J. C. Homann, perhaps realizing that he would not long survive his father, stipulated in his will that the company would be inherited by his two head managers, Johann Georg Ebersberger (1695 - 1760) and Johann Michael Franz (1700 - 1761), and that it would publish only under the name 'Homann Heirs'. This designation, in various forms (Homannsche Heirs, Heritiers de Homann, Lat Homannianos Herod, Homannschen Erben, etc.) appears on maps from about 1731 onwards. The firm continued to publish maps in ever-diminishing quantities until the death of its last owner, Christoph Franz Fembo (1781 - 1848). More by this mapmaker...