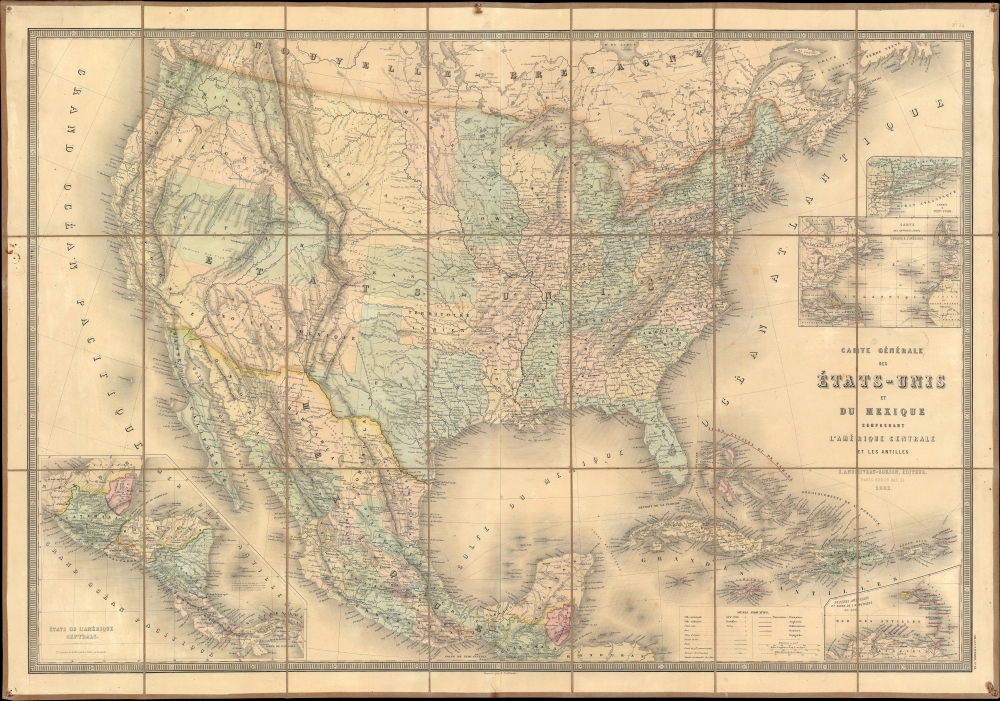

1862 Andriveau-Goujon and Vuillemin Map of the United States and Mexico

EtatsUnis-andriveau-1862

Title

1862 (dated) 26.75 x 38 in (67.945 x 96.52 cm) 1 : 7143000

Description

Colona and Shoshone: Proposed Territories

Two early regional names appear: Colona, roughly corresponding to Colorado, and Shoshone, which would soon become the Idaho Territory. Colona was a proposed territory roughly corresponding to modern-day Colorado. A proposal for 'Colona,' occupying the mountainous western parts of what was then Nebraska and Kansas, was put forth in 1859. The hope was for territorial status to enable self-governance, regulation, and administration of what was quickly becoming one of America's greatest gold and silver mining centers. Congress, focused on the struggle between slave and free states in the raucous lead-up to the American Civil War (1861 - 1865), found it easier to ignore the petition. Nonetheless, Colorado was recognized as a territory two years later, in 1861. The Colona petition was largely forgotten.Shoshone was a proposed new territory roughly corresponding to modern-day Idaho. The Shoshone are a group of Native American tribes that live in the northwest United States. 'Shoshone' was used generically to refer to their ranging lands and was even proposed as an official territory name. Modern-day Dakota and Idaho are believed to be derived from Shoshone words. The Idaho Territory was incorporated in 1863.

Dacotah (Dagotah) and Minnesota

During the nearly three-year period between Minnesota's statehood on May 11, 1858, and the creation of the Dakota Territory on March 2, 1861, the Pembina Region between the Missouri River and Red River, Minnesota's newly-created western border, was unattached to any territory. Following Minnesota's statehood, a provisional government was established in the Pembina to lobby for territorial self-governance. The Federal government ignored the proposal until the Dakota Territory was formed, which, upon its creation, included most of present-day Montana, Wyoming, and both North and South Dakota. Curiously, Dagotah is written in the same typeface as that of Shoshone, Colona, Nevada, and Arizona, leading us to believe the cartographers were justifiably confused by the ever-changing boundaries.Confederate Arizona

Although the Confederate States of America is not illustrated here, Confederate Arizona is and occupies the lower third of the New Mexico Territory. Confederate Arizona was a territory claimed by the Confederate States of America from 1861 until 1865. The idea for an Arizona Territory appeared as early as 1856 when the government of the Territory of New Mexico began to express concerns about being able to effectively govern the southern part of the territory, as it was separated from Santa Fe by the Jornada del Muerto, a particularly unforgiving stretch of desert. The New Mexico territorial legislature acted on these concerns in February 1858, approving a resolution in favor of creating an Arizona Territory, with a north-south border to be defined along the 32nd parallel. Impatiently waiting for Congress to approve the creation of the new territory, 31 delegates met at a convention in Tucson in April 1860 and drafted a constitution for the 'Territory of Arizona,' which was to be organized out of the New Mexico Territory below 34th parallel. The convention even elected a territorial governor and a delegate to Congress. Congress, however, was reluctant to act. Anti-slavery Representatives knew that the proposed territory was located below the line of demarcation set forth by the Missouri Compromise for the creation of new slave and free states, and they were not inclined to create yet another slave state. Thus, Congress never ratified the proceedings of the Tucson convention, and the Provisional Territory was never considered a legal entity.Further Historical Context

At the beginning of the Civil War, support for the Confederacy ran high in the southern parts of the New Mexico Territory. Local concerns drove this sentiment, including a belief that the war would lead to an insufficient number of Federal troops to protect the citizens from the Apache, while others simply felt neglected by the government in Washington. Also, the Butterfield Overland Mail Route (an overland mail and stagecoach route from Memphis and St. Louis to San Francisco) was closed in 1861, depriving the people of Arizona of their connection to California and the East Coast.Historical Context Continued

All of these factors led the people of the southern New Mexico Territory, or the Arizona Territory, to formally call for secession, and a convention adopted a secession ordinance on March 16, 1861, with a subsequent ordinance ratified on March 28, establishing the provisional territorial government of the Confederate 'Territory of Arizona.' The Confederate Arizona Territory was officially proclaimed on August 1, 1861, following Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. Baylor's victory over Union forces in the First Battle of Mesilla, and the government of the Confederacy officially recognized the territory on February 14, 1862. However, by July 1862, Union forces from California, known as the 'California Column,' were marching on the territorial capital of Mesilla. Sent to protect California from a possible Confederate incursion, the 'California Column' drove Confederate forces out of the city, allowing them to retreat to Franklin, Texas. The territorial government fled as well and spent the rest of the war in 'exile.' First, they retreated to Franklin, then, after Confederate forces abandoned Franklin and all of West Texas, to San Antonio, where the 'government-in-exile' would spend the rest of the war. Confederate units from Arizona would fight for the rest of the war, and a delegate from Arizona attended both the First and Second Confederate Congresses.Confederate States of America?

With the inclusion of Confederate Arizona, the question of why the Confederacy was not included arises. There may be two reasons for this reality. First, the exclusion of the Confederacy may be a reflection of French history. Since the French Revolution of 1789, France had been through a revolutionary government (complete with its own calendar), a dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte, the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, the establishment of a liberal constitutional monarchy, another dictatorship, and finally, the establishment of the Second Empire in 1852. With all this political upheaval in the space of just over seventy years, Andriveau and Vuillemin may have considered the inclusion of the Confederacy to be superfluous. With their experience of life in France, no matter how the American Civil War ended, the geography of the United States was unlikely to change. On the other hand, it may also illuminate the politics of Andriveau and Vuillemin in that they overtly chose not to include the Confederacy. This may have been their showing support for the Union.A Closer Look at the Map Itself

Roads and railroads wind their way across the country, much more densely in the northern states. Individual states in both the U.S. and Mexico are shaded, and a key is included along the bottom border to explain the map. Four inset maps are included. The top illustrates Long Island and the 'entry into New York,' while the one just below depicts connections between the Old and New Worlds. In the lower right, an inset of the Lesser Antilles appears. Central America, from Mexico to Panama, is detailed in an inset in the lower left.Publication History and Census

This map was drawn by Alexandre Vuillemin and published by Eugène Andriveau-Goujon in 1862. We know three examples. They are part of the collections at the University of Virginia, Benedictine College, and the University of Texas. It is scarce on the market and has only appeared a handful of times in the last decade.CartographerS

Eugène Andriveau-Goujon (1832 - 1897) was a map publisher and cartographer active in 19th century Paris. The firm was created in 1825 when Eugène Andriveau married the daughter of map publisher Jean Goujon - thus creating Andriveau-Goujon. Maps by Andriveau-Goujon are often confusing to identify as they can be alternately singed J. Goujon, J. Andriveau, J. Andriveau-Goujon, E. Andriveau-Goujon, or simply Andriveau-Goujon. This refers to the multiple generations of the Andriveau-Goujon dynasty and the tendency to republish older material without updating the imprint. The earliest maps to have the Andriveau-Goujon imprint were released by Jean Andriveau-Goujon. He passed the business to his son Gilbert-Gabriel Andriveau-Goujon, who in 1858 passed to his son, Eugène Andriveau-Goujon, under whose management the firm was most prolific. Andriveau-Goujon published numerous fine pocket maps and atlases throughout the 19th century and often worked with other prominent French cartographers of the time such as Brue and Levasseur. The firm's stock was acquired by M. Barrère in 1892. More by this mapmaker...

Alexandre Aimé Vuillemin (1812 - 1880) was an engraver, publisher, and editor based in Paris, France in the middle of the 19th century. Despite a prolific publishing career, much of Vuillemin's life is shrouded in mystery. In 1852, he married Josephine Caroline Goret and they had at least one child, Ernestine Adèle Vuillemin, later in the same year. What is known is that his studied under the prominent French Auguste Henri Dufour (1798 - 1865). Vuillemin's most important work his detailed, highly decorative large format Atlas Illustre de Geographie Commerciale et Industrielle. Learn More...