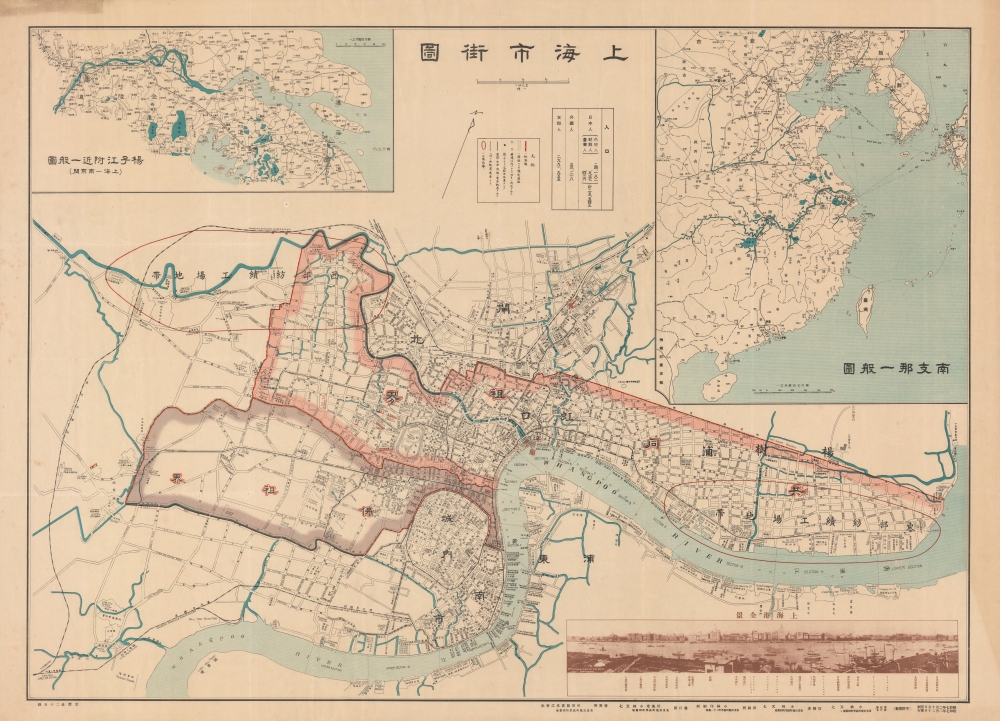

1932 Kobayashi Map of Shanghai showing Textile Area w/ Bund

ShanghaiTextile-kobayashi-1932-2$1,800.00

Title

上海市街圖 / Shanghai Street Map.

1932 (dated) 29 x 40.5 in (73.66 x 102.87 cm) 1 : 15840

1932 (dated) 29 x 40.5 in (73.66 x 102.87 cm) 1 : 15840

Description

A rare large-format 1932 (Showa 7) bilingual Japanese-English map of Shanghai with a photo of the Bund in the lower right. It was issued in the midst of hostilities between Imperial Japan and the Republic of China, a brief war known as the January 28 Incident or Shanghai Incident.

Against this background, a group of ultranationalist Nichiren monks provoking Chinese residents was attacked in Shanghai. In the following weeks, back and forth acts of violence were launched by provocateurs and both sides began to reinforce their militaries. The situation was complicated by Shanghai's divided jurisdiction and multinational elite, who preferred making money to fighting wars. The foreign concessions were expected to be safe from any conflict but fighting nevertheless spilled over into the Japanese-inhabited portion of the International Settlement (Hongkou or Hongkew).

Once fighting commenced on a large scale, the Chinese Nationalist troops performed better than expected, concentrating in Zhabei in order protect the strategically important Shanghai Railway Station, through which supplies and reinforcements could be readily delivered. Still, after weeks of intense fighting and failed negotiations, the better armed and supplied Japanese troops began to make costly gains, convincing Chiang Kai-Shek and his commanders to pull back from the city. Japan was not in a position to pursue a full-scale war and both sides began to negotiate towards a ceasefire which saw the immediate vicinity around Shanghai 'demilitarized'.

In retrospect, the 1932 fighting was a preview of the even more intense battle for Shanghai in the autumn of 1937, which began the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was largely the same areas - Zhabei and Hongkou - which saw fighting and widespread destruction in both conflicts. The fighting in 1932 caused a surge of refugees into the relative safety of the foreign concessions, as would be the case on a larger scale in 1937. Even the course of the fighting followed a similar pattern, with Chinese troops' determination overcoming their technological inferiority but with them ultimately being driven away from the city by Japanese reinforcements. In the waning days of the 1932 conflict, the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo was established, but the Japanese government led by Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi refused to formally acknowledge it, a sign of the rift between the military and civilian government. On May 15, Inukai was assassinated by ultranationalist junior military officers, who were subsequently given a light sentence, eroding the rule of law and allowing the military to exert greater control over Japanese politics.

Due to the extraterritoriality clauses of the Treaty of Nanjing and subsequent 'unequal treaties,' over time the areas where Westerners resided effectively became exempt from Chinese jurisdiction. In 1862, the French split with the Americans and British, creating a distinct French Concession, causing the 'Anglos' to form the International Settlement (divided at Avenue Edward VII and Avenue Foch, today's Yan'an Road). As a strategically located entrepot near the mouth of the Yangzi River, Shanghai quickly became a gateway to the entire Yangzi Delta. The light administration of the foreign concessions led to the city's reputation for economic dynamism, multiculturalism, crime, drugs, prostitution, and urban poverty.

The British influence was particularly strong in the International Settlement, but the city's elite was a cosmopolitan mix of Europeans, Americans, Japanese, Chinese, and others. Trading diasporas from across China and the globe set up shop there, including Baghdadi Jews, whose names (Kadoorie, Sassoon) were synonymous with Shanghai's high society. Since the exact sovereign status of the treaty ports was unclear, Shanghai became a refuge for Chinese fleeing the law or political repression, as well as stateless individuals and refugees, including White Russians and Viennese Jews fleeing the Nazis. Multiple nationalities also formed a subaltern stratum of police officers, servants, small business owners, and entertainers, including Parsis and Sikhs, Annamese, Koreans, Russians, Portuguese (Macanese), and Filipinos. However, the largest component of the city's population by far, including in the foreign concessions, were Chinese from near and far. Traders, absentee landowners, intellectuals, and professionals composed the Chinese elite and middle classes, while the city's working class tended to be migrants from the nearby countryside or further north in Jiangsu Province.

At the time this map was made, the treaty port era was at its peak, but signs of its ultimate doom were already apparent. The city's elite was splitting along national lines due to geopolitics, especially the growing conflict between China and Japan. China's partial reunification in 1926 brought an ambitious, anti-imperial government to power that was determined to end the 'unequal treaties.' And the growth of an industrial working class in the city spawned left-wing political movements, including the Chinese Communist Party, founded in the French Concession in July 1921.

A Closer Look

Coverage includes the foreign concessions, 'old' Chinese city, and nearby urbanized areas, especially the industrialized neighborhoods on the north side of the city. Inset maps in the upper left and right quadrants detail the general area and the Yangtze River and the eastern coast of China, respectively. 'East' and 'West' textile manufacturing zones are outlined in red and numerous textile mills and warehouses are labeled. Throughout, street names, schools, hospitals, factories, consulates, and more are labeled with both their Chinese and English names. However, the English is highly imperfect, suggesting that Kobayashi or someone in his firm copied the names from an English-language map, thus 'Uffer Section' instead of Upper, 'Dok' instead of dock, 'Ahsenal' instead of arsenal, and so on.The Shanghai Incident of 1932

The conflict of January 28th, 1932, also known as the Shanghai Incident, was a precursor to the Second Sino-Japanese War, which would begin five years later with an even more destructive battle for Shanghai. The roots of the 1932 conflict lie in increasingly aggressive Japanese imperialism, specifically the unprovoked and unauthorized invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 by the hypernationalist Kwantung Army (Kantōgun). The Chinese government was in a difficult position, as the country was disunified and weak militarily; a full-scale conflict with Japan could prove disastrous, but popular anger against Japanese imperialism was intense and demanded a response.Against this background, a group of ultranationalist Nichiren monks provoking Chinese residents was attacked in Shanghai. In the following weeks, back and forth acts of violence were launched by provocateurs and both sides began to reinforce their militaries. The situation was complicated by Shanghai's divided jurisdiction and multinational elite, who preferred making money to fighting wars. The foreign concessions were expected to be safe from any conflict but fighting nevertheless spilled over into the Japanese-inhabited portion of the International Settlement (Hongkou or Hongkew).

Once fighting commenced on a large scale, the Chinese Nationalist troops performed better than expected, concentrating in Zhabei in order protect the strategically important Shanghai Railway Station, through which supplies and reinforcements could be readily delivered. Still, after weeks of intense fighting and failed negotiations, the better armed and supplied Japanese troops began to make costly gains, convincing Chiang Kai-Shek and his commanders to pull back from the city. Japan was not in a position to pursue a full-scale war and both sides began to negotiate towards a ceasefire which saw the immediate vicinity around Shanghai 'demilitarized'.

In retrospect, the 1932 fighting was a preview of the even more intense battle for Shanghai in the autumn of 1937, which began the Second Sino-Japanese War. It was largely the same areas - Zhabei and Hongkou - which saw fighting and widespread destruction in both conflicts. The fighting in 1932 caused a surge of refugees into the relative safety of the foreign concessions, as would be the case on a larger scale in 1937. Even the course of the fighting followed a similar pattern, with Chinese troops' determination overcoming their technological inferiority but with them ultimately being driven away from the city by Japanese reinforcements. In the waning days of the 1932 conflict, the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo was established, but the Japanese government led by Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi refused to formally acknowledge it, a sign of the rift between the military and civilian government. On May 15, Inukai was assassinated by ultranationalist junior military officers, who were subsequently given a light sentence, eroding the rule of law and allowing the military to exert greater control over Japanese politics.

Shanghai in the Treaty Port Era

Although it was already a sizable port by 1842, Shanghai expanded at a tremendous pace when it was designated a treaty port after the First Opium War (1839 - 1842). British and French traders and missionaries were leased land outside of the walled 'Chinese City' (城内, at center towards bottom), particularly along the waterfront that came to be known as the Bund (periled in a panoramic photograph at bottom-right), which housed numerous foreign and Chinese banks and trading houses, consulates, clubs, and high-end hotels and restaurants.Due to the extraterritoriality clauses of the Treaty of Nanjing and subsequent 'unequal treaties,' over time the areas where Westerners resided effectively became exempt from Chinese jurisdiction. In 1862, the French split with the Americans and British, creating a distinct French Concession, causing the 'Anglos' to form the International Settlement (divided at Avenue Edward VII and Avenue Foch, today's Yan'an Road). As a strategically located entrepot near the mouth of the Yangzi River, Shanghai quickly became a gateway to the entire Yangzi Delta. The light administration of the foreign concessions led to the city's reputation for economic dynamism, multiculturalism, crime, drugs, prostitution, and urban poverty.

The British influence was particularly strong in the International Settlement, but the city's elite was a cosmopolitan mix of Europeans, Americans, Japanese, Chinese, and others. Trading diasporas from across China and the globe set up shop there, including Baghdadi Jews, whose names (Kadoorie, Sassoon) were synonymous with Shanghai's high society. Since the exact sovereign status of the treaty ports was unclear, Shanghai became a refuge for Chinese fleeing the law or political repression, as well as stateless individuals and refugees, including White Russians and Viennese Jews fleeing the Nazis. Multiple nationalities also formed a subaltern stratum of police officers, servants, small business owners, and entertainers, including Parsis and Sikhs, Annamese, Koreans, Russians, Portuguese (Macanese), and Filipinos. However, the largest component of the city's population by far, including in the foreign concessions, were Chinese from near and far. Traders, absentee landowners, intellectuals, and professionals composed the Chinese elite and middle classes, while the city's working class tended to be migrants from the nearby countryside or further north in Jiangsu Province.

At the time this map was made, the treaty port era was at its peak, but signs of its ultimate doom were already apparent. The city's elite was splitting along national lines due to geopolitics, especially the growing conflict between China and Japan. China's partial reunification in 1926 brought an ambitious, anti-imperial government to power that was determined to end the 'unequal treaties.' And the growth of an industrial working class in the city spawned left-wing political movements, including the Chinese Communist Party, founded in the French Concession in July 1921.

Publication History and Census

This map was printed on February 15, 1932, and published on February 20. It was prepared and printed by Kobayashi Matashichi (小林又七), published by Senryūdō (川流堂), and was sold by Heiyō Tosho Kabushiki Kaisha (兵用圖書株式會社), a bookstore in Tokyo whose name strongly suggests ties to the military. The map is scarce, only being noted among the holdings of the National Diet Library, Cornell University, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.CartographerS

Kobayashi Matashichi (小林又七; fl. c. 1905 - 1943) was a prolific cartographer and publisher based in Tokyo who primarily made and published maps of Japan's growing empire in East Asia (Korea, Manchuria, China). He often worked with the publisher and distributor Senryūdō (川流堂, sometimes as 川流所). More by this mapmaker...

Senryūdō (川流堂, sometimes 川流所; fl. c. 1888 - 1950) was a Tokyo-based publisher that often produced maps of Japan and its empire in the early - mid 20th century/ Learn More...

Condition

Very good. Light wear along original fold lines. Closed margin tears professionally repaired on verso. Very slight loss at a few fold intersections.

References

OCLC 64691671. NDL Call No. (請求記号) YG821-5327.