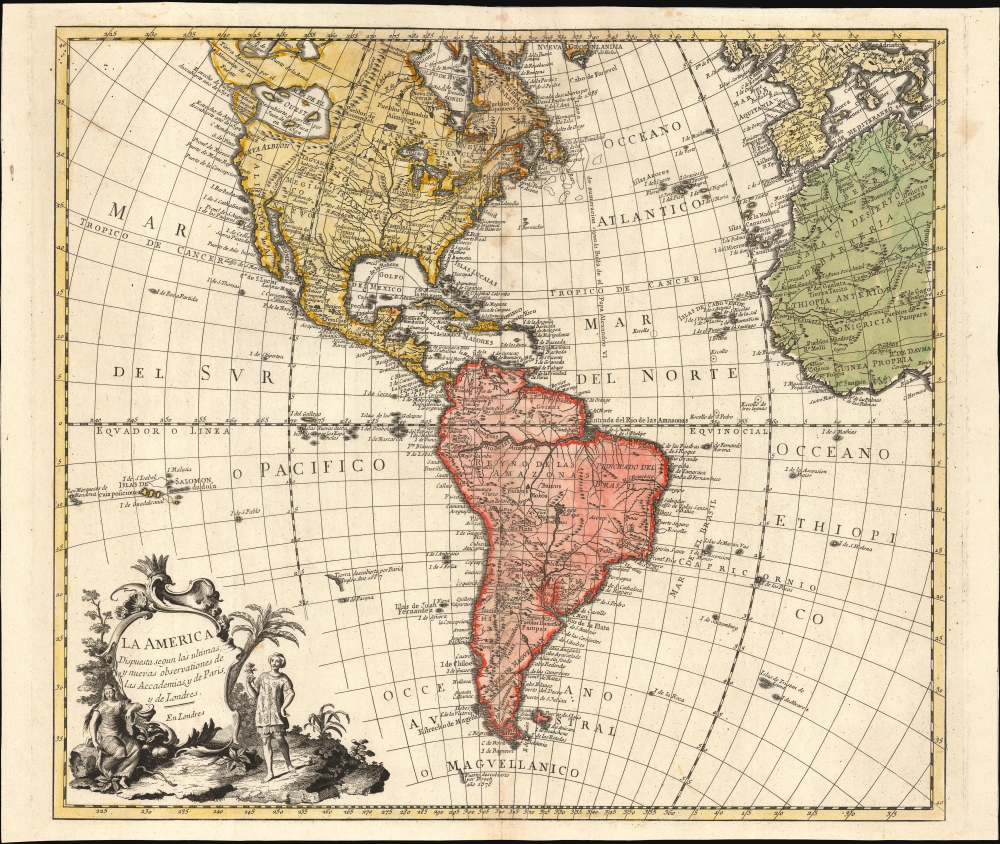

1756 Pedro Gendron Map of America with the Sea of the West

America-gendron-1756

Title

1756 (undated) 18 x 20.5 in (45.72 x 52.07 cm) 1 : 37000000

Description

An Unusual Imprint

The Spanish mapmaker first produced, in 1754, a virtually unacquirable map La America: dispuesta segun el Sistema de Mr. Hasius Profesor de Mathematicas en la Vniversidad de Witembergo, añadidos los ultimos descubrimientos por M. de Lisle. That map - probably printed in Madrid - was a translation of the authoritative mapping of Johann Matthias Hase, updated to include J.-N. De l'Isle's newly-theorized Sea of the West. The present work, printed in London, reproduced that work, without cartographic changes, on a new plate with a different cartouche and title.A Closer Look

The map's style and coloration are strongly reminiscent of German maps of the period which provided Gendron's source material. Hase's map, published by Homann Heirs in Nuremberg, was itself informed by French geographer Guillaume De l'Isle. This is most evident in North America in the reasonably accurate Mississippi and the depiction of the Great Lakes (devoid of the phantom islands introduced by Charlevoix). As with the maps of Hase and De l'Isle, this map covers the Western Hemisphere from Pole to Pole and from the Marquesas to include the Guinea coast of Africa, the Atlantic coast of Europe, and the Western Mediterranean Sea. The map's treatment of South American geography was mostly restricted to the coastline, with a broad-brush treatment for the Amazon and the Rio de la Plata. The South Pacific showed islands associated with the explorations of Magellan (1520), Mendana (1595), Quiros (1605). Identifiable islands include 'Terre decouverte par Davis,' the Marquesas, and the Galapagos Islands. Easter Island (Isla de Pascua) appears as well.The Sea of the West

In the Pacific Northwest, Gendron has included a feature not found on Hase's map: a tremendous bay penetrating almost twenty degrees of latitude into the continent called the Sea of the West. This bay is drawn from the Joseph-Nicolas de l'Isle's 1753 pamphlet Nouvelles cartes des decouvertes de l'Amiral de Fonte, et autres navigateurs espagnols, portugais, anglois, hollandois, françois et russes, dans les mers septentrionales. The text was the most thorough argument for the existence of this body of water, a concoction derived from the account of the fictional Admiral De Fonte and suspect interpretations of the actual discoveries of Juan de Fuca and Martin Aguilar. De l'Isle's illustrious elder brother Guillaume had speculated about the possible existence of the Sea of the West. However, he was unwilling to stake his reputation on it, going so far as to sue to prevent the mapmaker Nolin from plagiarizing De l'Isle's unpublished sketches of the notional sea. The younger Hoseph-Nicolas De l'Isle, eager to make boldly sensational claims before the French Academie des Sciences, had no such scruples: he produced several maps displaying the imaginary bay and its surrounding geography in his 1753 pamphlet. The delineation used here was unique to the map Carte Generale des Découvertes De l'Amiral de Fonte, which depicted the Sea of the West in conjunction with a tantalizing northwest passage attributed to de Fonte. While Gendron's map only shows the western extreme of the de Fonte geography along the top edge of the map, the selection of this source over the others presented by De l'Isle suggests the broad impact of the source map.Publication History and Census

This plate was engraved by an anonymous engraver (ostensibly in London) and closely copied from Pedro Gendron's 1754 map. McGuirk dates this London version of the map c. 1756 and notes that it was accompanied by a group of maps, likewise with this work's London imprint. These maps, all in Spanish, were produced uniformly based on Gendron's 1754 works. These included the world and the continents, as well as maps of individual European countries. Lacking authorial or publisher's imprint or date, it is not known whether they are Gendron's directly or if they are the work of an entirely unrelated publisher. Both versions of the map are rare: each is cataloged by institutional collections in a single copy - this version being listed solely by the University of Bern. Despite its institutional scarcity, this version has appeared on the market from time to time in recent years.CartographerS

Pedro Gendron (fl. 1750-1760) was a Spanish cartographer and publisher active in the mid-18th century. Nothing is known of his life, beyond his surviving works. He produced several known maps - of the continents, and of Portugal for example - published in Spain and Portugal between 1754 and 1756, as separate issues but likely with the intention of producing an atlas. In 1754 he contributed to the instructional work Méthodo Geográfico facil which was printed in Paris but was sold in Cadiz and Lisbon. He produced the maps for the Madrid-published 1757 Los Reynos de España y Portugal and the 1758 Atlas o Compendio Geographico, a student geography.

A group of eight maps, dated 1756 by McGuirk, were produced in London. These maps, all in Spanish, were produced uniformly based on Gendron's 1754 works. These included the world and the continents, as well as maps of individual European countries. These maps have no imprint and no date, so it is not known whether they are Gendron's directly or if they are the work of an entirely unrelated publisher. More by this mapmaker...

Johann Matthias Hase (January 14, 1684 - September 24, 1742) was a German cartographer, historical geographer, mathematician, and astronomer. Born in Augsburg, Hase was the son of a mathematics teacher, thus exhibited skill at mathematics early in life. He began attending the University of Helmstedt in 1701, where he studied mathematics under Rudolf Christian Wagner and then moved to the University of Leipzig to pursue a master's degree. He received his master's in 1707 and promptly returned to Augsburg to work as a teacher. However, he soon returned to Leipzig to serve as court master for two Augsburg patricians. There he became increasingly involved with geography, astronomy, and cartography as adjunct to the philosophical faculty. Hase was recommended for the position of chair of higher mathematics at the University of Wittenberg by his former professor, Christian Wolff, in 1715, but he was rejected. Five years later in 1720, however, he was named Professor of Mathematics at the University of Wittenberg. It is unclear exactly when Hase began working with the Homann Heirs firm, but he Hase compiled numerous maps under that imprint. He was also a prolific writer, publishing several treatises on universal history. Learn More...

Joseph-Nicolas De l'isle (April 4, 1688 – September 11, 1768) was a French astronomer and cartographer. He was the younger brother of the illustrious Geographer to the King, Guillaume De l'isle. He studied astronomy under Joseph Lieutaud and Jacques Cassini. In 1714 he entered the French Academy of Sciences; from 1719 to 1722 he was employed at the Royal observatory, and would meet Halley in 1724. In 1725 he was among the Western academics invited to Saint Petersburg by Tsar Peter the Great; his appointment to the Russian Academy would be both lucrative and academically to his profit, giving him access to the most current surveys of the easternmost reaches of the Russian Empire, including the revelations of Vitus Bering. He personally participated in expeditions to Siberia, with the object of studying astronomical events observations but also making cartographic, ethnographic and zoological observations. He was invited to collaborate with Ivan Kirilov on a planned atlas of the Russian Empire, but disagreements about methodology limited his engagement and the Atlas was abandoned at Kirilov's death in 1737. De l'Isle's extreme rigor, too proved to be frustratingly slow for the Academy, leading to his dismissal from the Atlas project in 1740. Accusations that he was sending secret documents to France surfaced as well. As De l'Isle's position grew increasingly untenable, he would request permission to leave Russia in 1743, which he would do in 1747. Ironically, the Atlas Rossicus would be published under De l'Isle's name; historians disagree whether the honor was justified. Upon his return to France, De l'Isle would vigorously publish maps containing the geographical data he gathered during his Russian tenure, to the extent that the accusations of his theft of secret Russian cartographic information appear credible. He would work extensively with his nephew-in-law, Philippe Buache, in publicizing an array of maps revealing the Russian discoveries in conjunction with an array of less credible cartographic revelations in the Pacific Northwest of America. Later, he would be instrumental in spurring the international effort to coordinate observations of the 1761 Transit of Venus, despite the execution of the observations being interfered with by the Seven Years' War. Learn More...