This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1791 Sayer Map of Charleston and Charleston Harbor, South Carolina

CharlestonBarHarbor-sayer-1791

Title

1791 (dated) 20.25 x 27.75 in (51.435 x 70.485 cm) 1 : 31680

Description

Looking at the Map

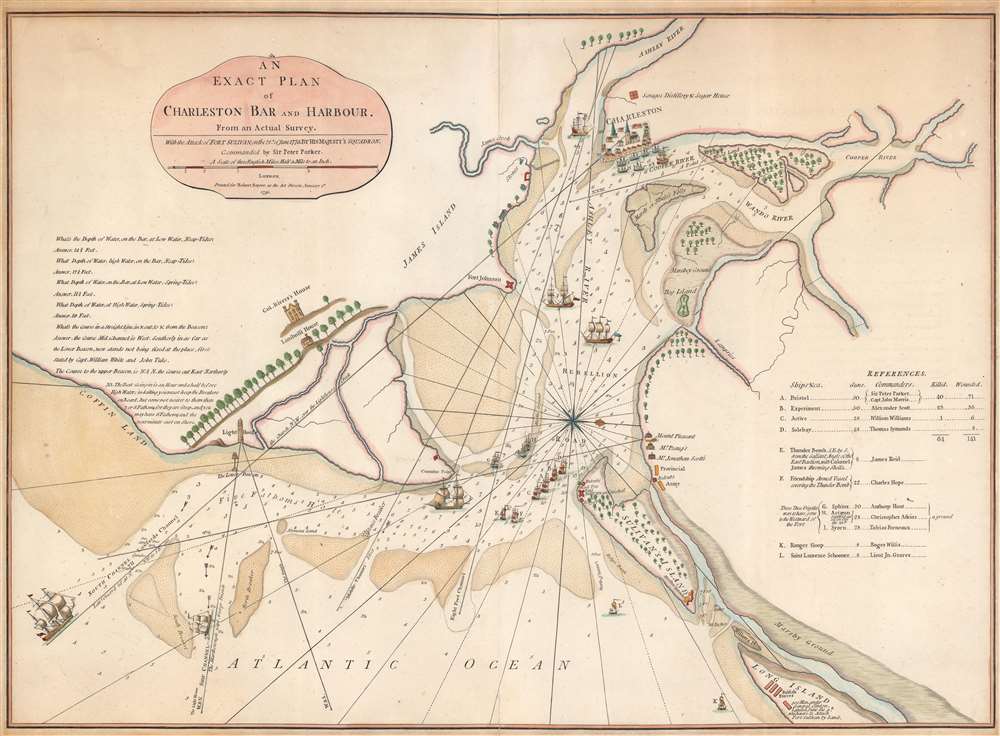

The map is oriented toward the west, underscoring its nautical chart origins - as this is how ships would approach Charleston Harbor. The British fleet appears to the left of Fort Sullivan, with alphanumeric labeling corresponding to a table near the right border, noting names, armaments, commanders, and casualties. Positions of Patriot forces are highlighted in orange, including the defenders at the north end of Sullivan's Island. Charleston Bar, a series of submerged shoals at the mouth of the harbor, is broken by several navigable channels. Other landmarks, including a lighthouse, coastal houses, and islands, are also illustrated.Background to the Battle

After the 1775 outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, British forces initially concentrated on the Patriot power center of Boston. By the end of 1775, having suffered significant losses, the British strategy refocused on the southern colonies - where there was believed to be significant Loyalist support. To that end, a force under Major General Charles Cornwallis (1738 - 1805) was dispatched from Ireland on February 13, 1776. Meanwhile, British Major General Henry Clinton's (1730 - 1795) army left Boston to join forces with Cornwallis' fleet off Cape Fear, North Carolina.A Delay and a Decision

When Clinton arrived at Cape Fear on March 12, he expected to find Cornwallis and the fleet waiting. Instead, the first ships did not arrive until April 18, with Cornwallis himself finally arriving on May 3. The delay gave the North Carolina militia time to mobilize and defeat the local Scottish Loyalists the British hoped to reinforce, leaving North Carolina firmly in Patriot hands. Cornwallis and Clinton were forced to reconsider their options - either move north to reinforce the Chesapeake Bay or attempt retake Charleston, and thus control the southern theater. Receiving reconnaissance that the defenses on Sullivan's Island were in 'so unfinished a State as to be open to a Coup de Main', they decided to attack Charleston.American Defenses

Patriot Colonel William Moultrie (1730 - 1805), a veteran of the 1761 Anglo-Cherokee War, commanded the defense of Charleston. To prevent the British fleet from landing, he ordered fortifications and a battery built on Sullivan's Island, which large vessels had to pass when entering Charleston Harbor. When the British arrived, Fort Sullivan was little more than a square stand of palmetto logs fortified only on the seaward side. The wall was 500 feet long, 20 feet high, 16 feet wide, and filled with sand to retard incoming fire. Just 31 canon and 435 men defended the fort.The Battle of Sullivan's Island

The British fleet arrived on June 1, and by June 8 crossed Charleston Bar, anchoring at Five Fathom Hole. The 9-ship fleet totaled nearly 300 canon, including two fifty-gun ships: the flagship Bristol and the Experiment. The British landed 2,200 troops on Long Island (across modern-day Breach Inlet from Sullivan's Island) on June 7, under the impression that Breach Inlet could be crossed on foot. This was not so, as the channel was at least shoulder deep. With a ground advance impossible, the fleet commander, Admiral Hyde Parker (1739 - 1807), began bombarding the hasty defenses on Fort Sullivan on June 28, 1776. Clinton meanwhile, attempted to land troops on the northern end of the island but was driven off under intense grape shot. Three of Parker's frigates also tried to flank Fort Sullivan, but ran aground on an uncharted sandbar (maps are important!). Two of ships were refloated, but the third was skuttled. At the same time, Fort Sullivan's palmetto-wood defenses proved both pliable and sturdy, effectively absorbing the incoming canon fire.British Naval Defeat

All hope of a British victory disappeared by early evening. Parker's fleet fired 7,000 rounds and burned 12 tons of powder. The Patriots (who faced a powder shortage) conserved their ammunition, but made their shots count. They fired just 960 rounds, burning only 4,766 pounds of powder. Even with an extreme disadvantage in firepower, Patriot defenders dealt disproportionate damage while suffering far fewer losses. Bristol was struck over 70 times and suffered 40 killed and 71 wounded. On the Experiment, 23 were killed and 56 wounded, with the ship itself suffering extreme damage. Of the Patriot defenders, 12 were killed and 25 wounded.Publication History and Census

This map first published by Robert Sayer in 1776 for his rare North American Pilot, The present example is the second state, published in 1791. We note a single cataloged example in OCLC, at Biblioteca Nacional de España. Other known examples are held at the Huntington Library and the British Library. This map equally rare on the private market, as we note only two examples in recent years.Cartographer

Robert Sayer (1725 - January 29, 1794) was an important English map publisher and engraver active from the mid to late 18th century. Sayer was born in Sunderland, England, in 1725. He may have clerked as a young man with the Bank of England, but this is unclear. His brother, James Sayer, married Mary Overton, daughter-in-law of John Overton and widow of Philip Overton. Sayer initially worked under Mary Overton, but by December of 1748 was managing the Overton enterprise and gradually took it over, transitioning the plates to his own name. When Thomas Jefferys went bankrupt in 1766, Sayer offered financial assistance to help him stay in business and, in this way, acquired rights to many of the important Jefferys map plates as well as his unpublished research. From about 1774, he began publishing with his apprentice, John Bennett (fl. 1770 - 1784), as Sayer and Bennett, but the partnership was not formalized until 1777. Bennett retired in 1784 following a mental collapse and the imprint reverted to Robert Sayer. From 1790, Sayer added Robert Laurie and James Whittle to his enterprise, renaming the firm Robert Sayer and Company. Ultimately, Laurie and Whittle partnered to take over his firm. Sayer retired to Bath, where, after a long illness, he died. During most of his career, Sayer was based at 53 Fleet Street, London. His work is particularly significant for its publication of many British maps relating to the American Revolutionary War. Unlike many map makers of his generation, Sayer was a good businessman and left a personal fortune and great estate to his son, James Sayer, who never worked in the publishing business. More by this mapmaker...