1896 Comissão Map of Chiromo, Shire Highlands (Mozambique / Malawi)

Chiromo-comissaocartographia-1896$800.00

Title

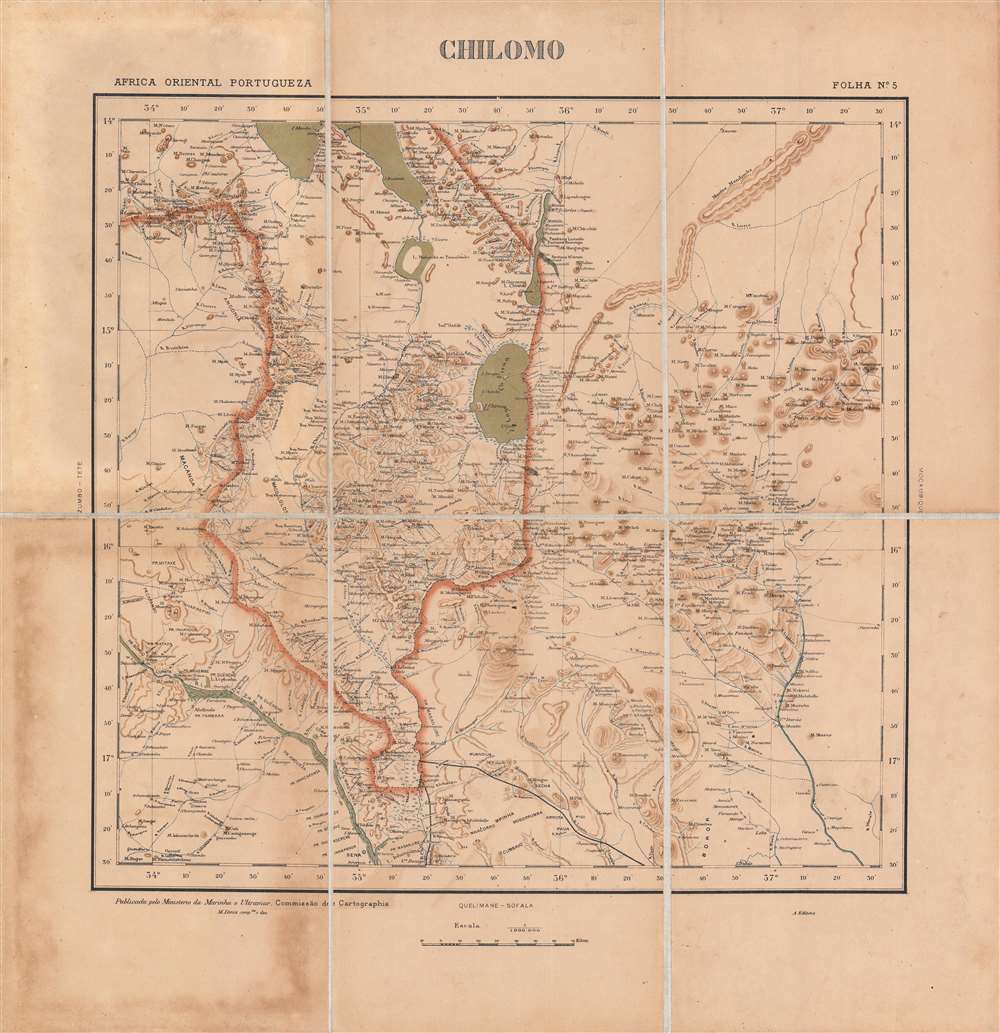

Chilomo - Africa Oriental Portugueza, Folha No. 5.

1896 (undated) 16.75 x 17 in (42.545 x 43.18 cm) 1 : 1000000

1896 (undated) 16.75 x 17 in (42.545 x 43.18 cm) 1 : 1000000

Description

This is a very rare c. 1896 map of the border region between the British Central Africa Protectorate and Portuguese Mozambique. This area had been hotly contested between the two colonial powers just a few years before and the border only recently settled in a contest that ensured British primacy in central Africa.

The presence of border 'fortresses' on both sides of the de facto border of the Ruo River is worth noting (Ft. Anderson, Ft. Eduardo, and Ft. Milange, now the sizable town of Milange). The railway lines at bottom existed on paper only. The northernmost one is the Ruo Railway, a project recently approved when this map was made. It was designed to connect Quelimane on the coast to the Ruo River but was never built (the area was prone to heavy flooding). The bottom line ultimately became the Sena Railway, though it was shifted further to the west.

Meanwhile, since the 1830s, the Portuguese attempted to expand their control over Mozambique, which was only nominally inland from the coast, by offering large estates (prazo) to colonists in the Lower Shire River Valley. Between 1879 - 1882, the Portuguese government claimed and then occupied lands up to the Ruo River, the ultimate border between the two territories.

More broadly, in the 1880s, the Portuguese tried to establish sovereignty over lands between Angola and Mozambique to build an East-West corridor across central Africa, a plan laid out in the famous 1885 Mapa cor-de-rosa (Pink Map). This project, motivated by the doctrine of effective occupation agreed to at the Berlin Conference of 1884 - 1885, ran afoul of the British, who were expanding into these same areas and who imagined a string of colonies running north and south 'from the Cape to Cairo' that would intersect with Portugal's claims.

Portuguese troops under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto attempted several times to make inroads with local chiefs in the Shire Highlands around Blantyre and establish a protectorate. In September 1889, Serpa Pinto crossed the Ruo River at Chiromo with a military expedition. At that point, the British Consul had left Blantyre but had set up a missionary named John Buchanan to act as consul in his absence. Without consulting the Foreign Office, Buchanan declared a Shire Highland Protectorate to fend off the Portuguese advances. The situation came to a head when Serpa Pinto's troops fought with troops of Kokolo chiefs aligned with the British and the Portuguese moved as far north as Katunga (here as Catunga).

In January 1890, the British sent an ultimatum that the Portuguese relinquish their claims laid out on the Pink Map and sign a treaty fixing the borders on terms favorable to the British. The much weaker Portuguese were forced to accept Britain's will and watch helplessly as British interests (mainly the British South Africa Company led by Cecil Rhodes) expanded into the lands they had recently claimed. The incident was an embarrassment for the young King Carlos I and for the entire nation, and was used as an opportunity by republican revolutionaries to stage a (failed) revolt in Porto. The monarchy's reputation never recovered from the episode; Carlos was assassinated along with his designated heir in 1908 and the monarchy was overthrown and abolished in 1910.

The 'Scramble for Africa' presented Portugal both risks and opportunities. But, as discussed above, they were incapable of challenging the British and had to grudgingly accept a secondary role among European colonial powers there. Despite their earlier antagonism, the British and Portuguese were both wary of German expansion in Africa in the late 19th century and collaborated against Germany during the First World War. Although Portugal was neutral at the start of the conflict, it supplied the British and French armies on the Western Front and was eventually drawn into the war on the Allied side in 1916, focusing mainly on protecting its African colonies.

In the interwar period, with the threat of anti-colonial movements looming, Portugal moved towards a notion of 'pluricontinental' nationhood. Nevertheless, with the wave of decolonization that followed World War II, Portugal faced the prospect of losing its colonies, but the country's Prime Minister and de facto dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, categorically refused decolonization and aimed to crush guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). Counter-insurgency efforts were largely successful as a short-term solution, but failed to resolve underlying problems, and when Salazar's successor Marcelo Caetano was toppled in a coup in 1974, Portugal's empire quickly collapsed. Angola and Mozambique then descended into protracted civil wars that became Cold War proxy conflicts that were only resolved years later.

A Closer Look

This map covers the mountainous territory that corresponds to present-day southern Malawi (within the red border) and surrounding areas in northwestern Mozambique, stretching from the southern shores of Lake Malawi (then Lake Nyasa) in the north to Villa de Senna (then Sena) in the south. It is extremely detailed, assiduously noting villages, rivers, and mountains. The map is titled 'Chilomo' (Chiromo), referring to an important town at the intersection of the Shire and Ruo Rivers.The presence of border 'fortresses' on both sides of the de facto border of the Ruo River is worth noting (Ft. Anderson, Ft. Eduardo, and Ft. Milange, now the sizable town of Milange). The railway lines at bottom existed on paper only. The northernmost one is the Ruo Railway, a project recently approved when this map was made. It was designed to connect Quelimane on the coast to the Ruo River but was never built (the area was prone to heavy flooding). The bottom line ultimately became the Sena Railway, though it was shifted further to the west.

The Anglo-Portuguese Crisis

In the decade or so before this map was made, the British and Portuguese were tussling for influence in this region. British missionaries had arrived in the 1860s and British interests expanded in their wake, including the African Lakes Corporation and a town at Blantyre (center, towards center-left), where a British Consul was stationed in 1883. Still, British settlers there were considered beyond the protection of their government.Meanwhile, since the 1830s, the Portuguese attempted to expand their control over Mozambique, which was only nominally inland from the coast, by offering large estates (prazo) to colonists in the Lower Shire River Valley. Between 1879 - 1882, the Portuguese government claimed and then occupied lands up to the Ruo River, the ultimate border between the two territories.

More broadly, in the 1880s, the Portuguese tried to establish sovereignty over lands between Angola and Mozambique to build an East-West corridor across central Africa, a plan laid out in the famous 1885 Mapa cor-de-rosa (Pink Map). This project, motivated by the doctrine of effective occupation agreed to at the Berlin Conference of 1884 - 1885, ran afoul of the British, who were expanding into these same areas and who imagined a string of colonies running north and south 'from the Cape to Cairo' that would intersect with Portugal's claims.

Portuguese troops under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto attempted several times to make inroads with local chiefs in the Shire Highlands around Blantyre and establish a protectorate. In September 1889, Serpa Pinto crossed the Ruo River at Chiromo with a military expedition. At that point, the British Consul had left Blantyre but had set up a missionary named John Buchanan to act as consul in his absence. Without consulting the Foreign Office, Buchanan declared a Shire Highland Protectorate to fend off the Portuguese advances. The situation came to a head when Serpa Pinto's troops fought with troops of Kokolo chiefs aligned with the British and the Portuguese moved as far north as Katunga (here as Catunga).

In January 1890, the British sent an ultimatum that the Portuguese relinquish their claims laid out on the Pink Map and sign a treaty fixing the borders on terms favorable to the British. The much weaker Portuguese were forced to accept Britain's will and watch helplessly as British interests (mainly the British South Africa Company led by Cecil Rhodes) expanded into the lands they had recently claimed. The incident was an embarrassment for the young King Carlos I and for the entire nation, and was used as an opportunity by republican revolutionaries to stage a (failed) revolt in Porto. The monarchy's reputation never recovered from the episode; Carlos was assassinated along with his designated heir in 1908 and the monarchy was overthrown and abolished in 1910.

Railways and Inter-imperial Relations

At the turn of the 20th century, both empires launched a railway building spree to strengthen their claims, but also signed agreements for railways to cross each other's territory, such as the line from Beira to Salisbury (Harare). The British were much faster to build railways in the region shown here, setting up the Shire Highlands Railway Company in Blantyre in 1901, which commenced operations in 1904. In 1912, an agreement between the British and Portuguese was signed to extend the railway to the south and eventually reach Dondo, near Beira, but progress was slow and the full line connecting the southern shore of Lake Malawi through Blantyre, Chiromo, Sena, and Nhamayabué (Mutarara), where it linked to an existing railway to Dondo, was not completed until the mid-1930s. The railway facilitated some important trade, especially the transport of coal and cotton from the region shown here to Beira, but was unprofitable overall. It did, however, serve as an important link between the two 'halves' of Mozambique on either side of the Zambezi, especially the Dona Ana Railway Bridge, completed in 1934.Portugal's 'Third Empire'

In the early 19th century, Portugal was no longer a great world power, and its empire was significantly reduced, especially after the independence of Brazil in 1822. But the empire did still maintain a string of colonies, the largest of which were Angola and Mozambique. Some Portuguese had ventured into the African interior in the early days of their colonial presence following Vasco da Gama's explorations and set up estates and trading post-garrisons, including at Sena. However, they were few and generally intermarried with the local population to the point that they lost Portuguese identity, while the estates were operated like independent fiefdoms rather than a shared colonial enterprise. Therefore, Portugal's control was mostly limited to coastal ports and most of the people it claimed to rule were effectively independent. In the early-mid 19th century, the government launched a renewed effort to move colonists further inland and strengthen direct control over the interior.The 'Scramble for Africa' presented Portugal both risks and opportunities. But, as discussed above, they were incapable of challenging the British and had to grudgingly accept a secondary role among European colonial powers there. Despite their earlier antagonism, the British and Portuguese were both wary of German expansion in Africa in the late 19th century and collaborated against Germany during the First World War. Although Portugal was neutral at the start of the conflict, it supplied the British and French armies on the Western Front and was eventually drawn into the war on the Allied side in 1916, focusing mainly on protecting its African colonies.

In the interwar period, with the threat of anti-colonial movements looming, Portugal moved towards a notion of 'pluricontinental' nationhood. Nevertheless, with the wave of decolonization that followed World War II, Portugal faced the prospect of losing its colonies, but the country's Prime Minister and de facto dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, categorically refused decolonization and aimed to crush guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). Counter-insurgency efforts were largely successful as a short-term solution, but failed to resolve underlying problems, and when Salazar's successor Marcelo Caetano was toppled in a coup in 1974, Portugal's empire quickly collapsed. Angola and Mozambique then descended into protracted civil wars that became Cold War proxy conflicts that were only resolved years later.

Publication History and Census

This map was compiled by M. Diniz of the Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias, an office within the Ministério da Marinha e Ultramar. It appears to be Sheet No. 5 in the in the collection Africa Oriental Portugueza (OCLC 945552666). The map has no known history on the market and is not cataloged independently in the holdings of any institution, while the entire collection is held by the Library of Congress, Yale University, and the Bibliotheek Universiteit van Amsterdam. However, it is unclear whether these institutions hold the present map based on their catalog descriptions, which only mention other maps in the collection. It is possible, then, that this is a unique example of this map.Cartographer

Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias (fl. c. 1883 - 1936), in its early years as 'Comissão de Cartographia das Colónias', was an office within the Ministério da Marinha e Ultramar tasked with surveying Portugal's colonies, primarily in Africa. It was dissolved in 1936 and replaced with Junta das Missões Geográficas e de Investigações Colonia. More by this mapmaker...

Condition

Good. Some soiling in bottom-left quadrant.