This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

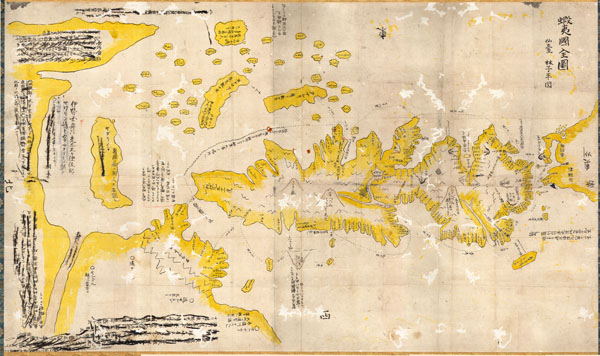

1795 Hayashi Shihei Japanese Manuscript Map of Hokkaido, Japan

Hokkaido-japan-1850$1,000.00

Title

Ezo No Kuni Zenzu (Map of the Ezo Region)

1785 (undated) 36 x 22 in (91.44 x 55.88 cm)

1785 (undated) 36 x 22 in (91.44 x 55.88 cm)

Description

This is an unusual 1785 manuscript map of the island of Hokkaido by the Japanese cartographer Hayashi Shihei. Oriented to the east, Shiehi has drawn Hokkaido in an unusual form, elongated on the north-south axis, such that it is barely recognizable to our modern sensibilities. The islands at the top of the map are the Japanese Kuriles. The northern tip of Honshu appears to the right. Sakhalin appears twice, both an island to the left of the Hokkaido, and as Karafuto, here drawn as part of the Asian continent. Shihei based the map on material presented to the Shogun before the Ezochi expedition of 1785-1786 more formally mapped the region.

This particular example has much of its original annotations blocked out - though they are still readable - and is clearly an example of early Japanese censorship. Shihei issued this map without the permission of the central government and, moreover, the parent work was highly critical of the Shogun's international policy. As such, this, like most Shihei maps, was never formally printed, and was instead transmitted only in manuscript form - as here. Most likely the present example found its way into official hands and was amended and blocked out in accordance with the Tokugawa policy of isolationism.

An exceptional discovery.

This particular example has much of its original annotations blocked out - though they are still readable - and is clearly an example of early Japanese censorship. Shihei issued this map without the permission of the central government and, moreover, the parent work was highly critical of the Shogun's international policy. As such, this, like most Shihei maps, was never formally printed, and was instead transmitted only in manuscript form - as here. Most likely the present example found its way into official hands and was amended and blocked out in accordance with the Tokugawa policy of isolationism.

An exceptional discovery.

Condition

Very good condition. Map has undergone some very fine traditional Japanese restoration including mounting and backing. Some of the original text has been scratched out – the reason for this remains a mystery.

References

OCLC 606373786. Woodward, D. and Harley, J. B. , The History of Cartography Volume Two, Book Two, p. 445 (illus).