This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

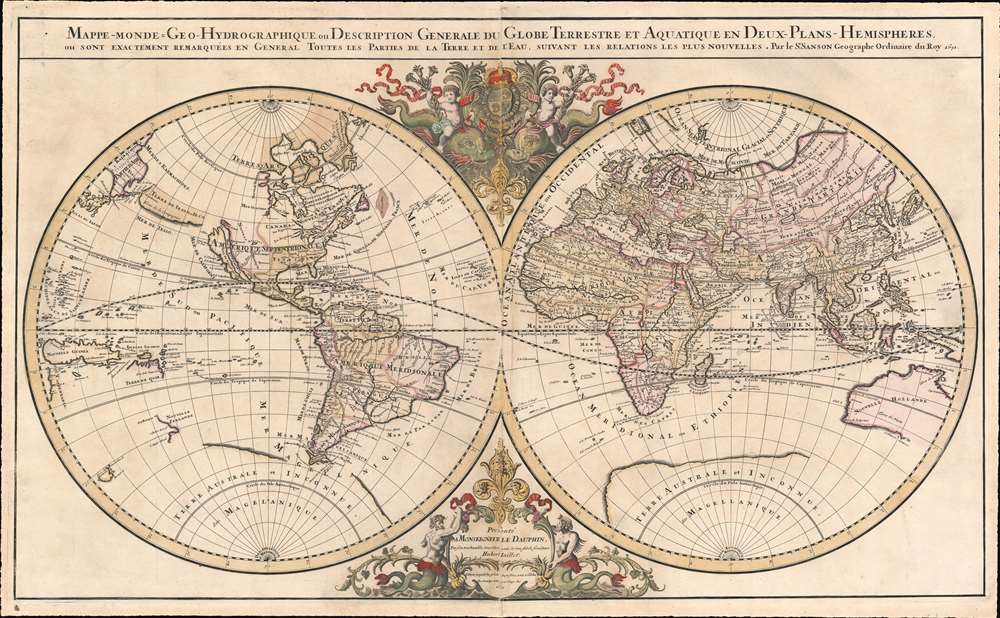

1691 Jaillot / Sanson Double Hemisphere World Map in Original Color

MappeMonde-jaillot-1691-2

Title

1691 (dated) 21 x 35 in (53.34 x 88.9 cm) 1 : 65000000

Description

The Map: California as an Island

Although the notion first appears in print in the early 16th century, the first maps showing California as an island would appear in England and the Netherlands in the 1620s. Sanson's wholehearted adoption of the myth in the middle of the 1600s would almost indelibly entrench the idea for the rest of the 17th century and well beyond Kino's debunking of the error in the early 18th century.New Mexico

East of the sea separating California from the mainland lies Nouveau Mexique. Santa Fe is shown on the banks of the Rio Norte, which is a conflation of the Rio Grande with the Colorado - the river is shown running from Santa Fe to the southwest rather than to the Gulf of Mexico. The river has its source in a gigantic (and imaginary) lake named Apache. This lake may result from Native American reports of the Great Salt Lake or another lake in the region brought back by the Onate and Coronado expeditions.Cities of Gold

In addition to Santa Fe, New Mexico is shown to contain the land of Quivira. Quivira, along with Cibola, was one of the Seven Cities of Gold from Spanish legend. (Each of the Seven Cities was thought to have been founded by one of the seven bishops of the Spanish city of Merida, who legend said fled with the city's riches when before the city was sacked by the Moors in 1150. With the discovery of the New World and the fabulous riches plundered by Cortez and Pizarro, the legend of the Seven Cities was recalled by European invaders of the new-found continent. Coronado, hearing tales of the rich Aztec homeland of Azatlan somewhere to the north believed he was hunting for Quivira in what is today the American southwest. Despite its nonexistence, Quivara would long be shown on maps before disappearing in the early 19th century.Canada and The Great Lakes

Sanson's geography of the northeastern portions of North America was more authoritative and accurate. Hudson's Bay appears in recognizable form, albeit with several openings to the west, suggestive of hoped-for connections with the Pacific Ocean. Sanson's mapping of the Great Lakes was the first to show all five lakes, although lakes Superior and Michigan are shown with their western reaches left unfinished, again suggesting the possibility of navigable water route to the Pacific.Colonial America

Although the Northeast is dominated by 'Canada ou Nouvelle France,' the claims of France's European rivals are grudgingly acknowledged. Nouvelle Angleterre (New England), Nouveau Pays Bas (New Netherland, that is to say modern New York) and even Nouvelle Suede (New Sweden, in New Jersey) are shown - though squeezed down to the coastline, with the place names relegated to the ocean. Virginia is also named.The American Southeast

In Spanish Florida, which extends north to include most of the American Southeast, Lake Apalache or the 'Great Freshwater Lake of the American Southeast' is noted. This lake, first mapped by De Bry and Le Moyne in the mid 16th century, is a mis-mapping of Florida's Lake George. While De Bry correctly mapped the lake as part of the River May or St. John's River, cartographers in Europe erroneously associated it with the Savannah River, which instead of flowing from the south to the Atlantic (Like the May), flowed almost directly from the Northwest. Lake Apalache was subsequently relocated somewhere in Carolina or Georgia, where Sanson maps it and where it would remain for several hundred years.South America and El Dorado

The Caribbean is well understood and relatively well detailed given the scale of the map. Southwards, despite the South American coastlands being well mapped, the interior was largely unknown, giving rise to rampant speculation. Explorers throughout the late 16th and early 17th century, enthralled by Pizarro's conquests in Peru and tales of other gold rich empires in the interior, were actively seeking El Dorado - which legend placed in the mythical city of Manoa, which in turn was shown by Sanson on the shores of the Lake Parima, near modern day Guyana, Venezuela, or northern Brazil. Manoa was first identified by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595. Raleigh did not visit the place himself due to the onset of the rainy season, but this does not prevent him from describes the city, based on indigenous accounts, as resting on a salt lake over 200 leagues wide. This lake, though no longer mapped as such, does have some basis in fact. Parts of the Amazon were, at the time dominated by a large and powerful Indigenous trading nation known as the Manoa. The Manoa traded the length and breadth of the Amazon. The onset of the rainy season inundated the great savannahs of the Rupununi, Takutu, and Rio Branco or Parima Rivers. This inundation briefly connected the Amazon and Orinoco river systems, opening an annual and well used trade route for the Manoans. The Manoans who traded with the Incans in the western Amazon, had access to gold mines on the western slopes of the Andes, and so, when Raleigh saw gold rich Indian traders arriving in Guyana, he made the natural assumption for a gold hungry European in search of El Dorado. When he asked the Orinocans where the traders were from, they could only answer, 'Manoa.' Thus did Lake Parime or Parima and the city of Manoa begin to appear on maps in the early 17th century. The city of Manoa and Lake Parima would continue to be mapped in this area until about 1800.Further south Sanson maps a large and prominent Laguna de Xarayes as the northern terminus of the Paraguay River. The Xarayes, a corruption of 'Xaraiés' meaning 'Masters of the River', were an indigenous people occupying what are today parts of Brazil's Matte Grosso and the Pantanal. When Spanish and Portuguese explorers first navigated up the Paraguay River, as always in search of El Dorado, they encountered the vast Pantanal flood plain at the height of its annual inundation. Understandably misinterpreting the flood plain as a gigantic inland sea, they named it after the local inhabitants, the Xaraies. The Laguna de los Xarayes almost immediately began to appear on early maps of the region and, at the same time, almost immediately took on a legendary aspect. The Lac or Laguna Xarayes was often considered to be a gateway to the Amazon and the Kingdom of El Dorado.

Africa

The seventeenth century mapping of Africa is similar to that of the New World, in that geographers were well informed of the coastline but for the most part ignorant of the interior. Sanson followed the Ptolemaic two-lakes-at-the-base-of-the-Montes-de-Lune theory, as did every other mapmaker of his era. Just south of Sanson's Lake Zaire lies the Kingdom of Monomatapa. This region of Africa held a particular fascination for Europeans since the Portuguese first encountered it in the 16th century. At the time, this was a vast empire called Mutapa or Monomotapa that maintained an active trading network with faraway partners in India and Asia. As the Portuguese presence in the region increased in the 17th century, the Europeans began to note that Monomatapa was particularly rich in gold. They were also impressed with the numerous, well-crafted stone structures, including the mysterious nearby ruins of Great Zimbabwe. This combination led many Europeans to believe that Ophir or King Solomon's Mines, a sort of African El Dorado, must be hidden in the area. Monomotapa did in fact have rich gold mines in the 16th and 17th centuries, but most of these had been exhausted by the 1700s.Asia

Sanson's mapping of Asia Minor, Persia and India is fairly accurate. The Caspian Sea is corrected to a north-south axis though its form is still poorly-understood. Numerous Silk Route cities are named throughout Central Asia including Samarkand, Tashkirgit, Bukhara, and Kashgar. Far to the north he associates Tartaria, Mongolia, and Siberia with the Biblical lands of Gog and Magog - a common error, related to European terror of the Mongol Invasions.Sanson maps, but does not name, the apocryphal Lake of Chiamay roughly in what is today Assam, India. Early cartographers postulated that such a lake must exist to source the four important Southeast Asian river systems: the Irrawaddy, the Dharla, the Chao Phraya, and the Brahmaputra. This lake began to appear in maps of Asia as early as the 16th century and persisted well into the mid 18th century. Its origins are unknown but may originate in a lost 16th century geography prepared by the Portuguese scholar Jao de Barros. It was also heavily discussed in the journals of Sven Hedin, who believed it to be associated with Indian legend that a sacred lake linked several of the holy subcontinent river systems. There are even records that the King of Siam led an invasionary force to take control of the lake in the 16th century. Nonetheless, the theory of Lake Chiamay was ultimately disproved and it disappeared from maps entirely by the 1760s.

An Early, Peninsular Korea, Speculative Northern Japan

Korea appears here as a peninsula; its narrow form derives from having been its rudimentary connection to the mainland - the peninsula otherwise resembles its insular depiction on earlier 17th century maps. Split between the two hemispheres of this map, the southern Japanese Islands are shown with some accuracy: for example, Edo or Tokyo Bay is clearly recognizable and several Japanese cities, including Yendo (Edo or Tokyo) are noted. Hokkaido is shown attached to the continent, however, and the Japanese Kuril Islands extend eastward to a massive Terre de la Compagnie, also named Terre de Jesso on the map. Alhough these are names usually associated with Hokkaido on early maps, this land mass is more commonly called Gama or Gamaland. Gama was supposedly discovered in the 17th century by a mysterious figure known as Jean de Gama. Various subsequent navigators claim to have seen this land and it appeared in numerous maps well into the late 18th century. At times it was associated with Hokkaido, in Japan, and at other times with the mainland of North America. On this map we are struck by its uncanny resemblance to Gerhard Muller's peninsula which emerged in the late 18th century. Based on numerous sightings but no significant exploration of the Aleutian Islands, Muller postulated that the archipelago was in fact a single land mass. This he mapped extending from the North American mainland towards Asia much as the 'Terre de Compagnie' does on this map. It is not inconceivable that navigators sailing in the northern seas from Asia could have made this same error in the 16th and 17th centuries.Early South Pacific Discoveries

Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific were virtually unknown to European explorers; the depiction of these lands on all maps from the middle of the 17th century until Cook's voyages is based on the 1642 mapping of Abel Tazman in 1642 mapping. For over a century, only a portion of the west coasts of Australia and New Zealand were to appear on maps, and likewise only the southern coastline of Tasmania. A mysterious 'Terre de Quir' is shown as well: a great landmass supposedly discovered by the 16th century Spanish navigator and religious zealot Pedro Fernandez de Quiros. Quiros set sail in search of the speculative southern continent and may in fact have discovered several important South Seas islands, however, he stopped just shy of glory and turned around shortly before sighting New Zealand. Even so, Quiros was a voracious self promoter and descriptions of his findings were circulated throughout Europe. Terre de Quir or Terre de Quiros appears on various maps of the region until put to rest by the 18th century explorations of Captain Cook.Antarctica

16th century maps had shown a Southern Hemisphere dominated by a great, imaginary, southern continent typically named 'Terre Australe Incognita'. Despite the tenacity of geographical authorities on the matter, Cartographers of the 17th century would gradually whittle away the coastline of the massive continent as one expedition after another failed to bump into any of it. The depiction of Antarctica here, dating from the 1660s, shows the coastline pared away from 'Nouvelle Holland' and Magellanica; by the end of the century, most maps would dispense with the continent entirely as geographers came to admit the extent to which the 'Terre Australe' was in fact 'incognita'. Antarctica itself was not truly discovered until Edward Bransfield and William Smith sighted the Antarctic Peninsula in 1820.Publication History and Census

The first printing of Jaillot's map for inclusion in his Atlas Nouveau was in 1674 (see Shirley 462.) The atlas was evidently successful: the map would have to be re-engraved at least three times. Shirley identifies four different plates. The present example is plate four, in its first state of 1691. The separate map is catalogued twenty times in institutional collections. The Atlas Nouveau is similarly represented, in various editions.CartographerS

Alexis-Hubert Jaillot (c. 1632 - 1712) followed Nicholas Sanson (1600 - 1667) and his descendants in ushering in the great age of French Cartography in the late 17th and 18th century. The publishing center of the cartographic world gradually transitioned from Amsterdam to Paris following the disastrous inferno that destroyed the preeminent Blaeu firm in 1672. Hubert Jaillot was born in Franche-Comte and trained as a sculptor. When he married the daughter of the Enlumineur de la Reine, Nicholas I Berey (1610 - 1665), he found himself positioned to inherit a lucrative map and print publishing firm. When Nicholas Sanson, the premier French cartographer of the day, died, Jaillot negotiated with his heirs, particularly Guillaume Sanson (1633 - 1703), to republish much of Sanson's work. Though not a cartographer himself, Jaillot's access to the Sanson plates enabled him to publish numerous maps and atlases with only slight modifications and updates to the plates. As a sculptor and an artist, Jaillot's maps were particularly admired for their elaborate and meaningful allegorical cartouches and other decorative elements. Jaillot used his allegorical cartouche work to extol the virtues of the Sun King Louis IV, and his military and political triumphs. These earned him the patronage of the French crown who used his maps in the tutoring of the young Dauphin. In 1686, he was awarded the title of Geographe du Roi, bearing with it significant prestige and the yearly stipend of 600 Livres. Jaillot was one of the last French map makers to acquire this title. Louis XV, after taking the throne, replaced the position with the more prestigious and singular title of Premier Geographe du Roi. Jaillot died in Paris in 1712. His most important work was his 1693 Le Neptune Francois. Jalliot was succeeded by his son, Bernard-Jean-Hyacinthe Jaillot (1673 - 1739), grandson, Bernard-Antoine Jaillot (???? – 1749), and the latter's brother-in-law, Jean Baptiste-Michel Renou de Chauvigné-Jaillot (1710 - 1780). More by this mapmaker...

Nicolas Sanson (December 20, 1600 - July 7, 1667) and his descendants were the most influential French cartographers of the 17th century and laid the groundwork for the Golden Age of French Cartography. Sanson was born in Picardy, but his family was of Scottish Descent. He studied with the Jesuit Fathers at Amiens. Sanson started his career as a historian where, it is said, he turned to cartography as a way to illustrate his historical studies. In the course of his research some of his fine maps came to the attention of King Louis XIII who, admiring the quality of his work, appointed Sanson Geographe Ordinaire du Roi. Sanson's duties in this coveted position included advising the king on matters of geography and compiling the royal cartographic archive. In 1644, he partnered with Pierre Mariette, an established print dealer and engraver, whose business savvy and ready capital enabled Sanson to publish an enormous quantity of maps. Sanson's corpus of some three hundred maps initiated the golden age of French mapmaking and he is considered the 'Father of French Cartography.' His work is distinguished as being the first of the 'Positivist Cartographers,' a primarily French school of cartography that valued scientific observation over historical cartographic conventions. The practice result of the is less embellishment of geographical imagery, as was common in the Dutch Golden Age maps of the 16th century, in favor of conventionalized cartographic representational modes. Sanson is most admired for his construction of the magnificent atlas Cartes Generales de Toutes les Parties du Monde. Sanson's maps of North America, Amerique Septentrionale (1650), Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride (1656), and La Canada ou Nouvelle France (1656) are exceptionally notable for their important contributions to the cartographic perceptions of the New World. Both maps utilize the discoveries of important French missionaries and are among the first published maps to show the Great Lakes in recognizable form. Sanson was also an active proponent of the insular California theory, wherein it was speculated that California was an island rather than a peninsula. After his death, Sanson's maps were frequently republished, without updates, by his sons, Guillaume (1633 - 1703) and Adrien Sanson (1639 - 1718). Even so, Sanson's true cartographic legacy as a 'positivist geographer' was carried on by others, including Alexis-Hubert Jaillot, Guillaume De L'Isle, Gilles Robert de Vaugondy, and Pierre Duval. Learn More...