This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

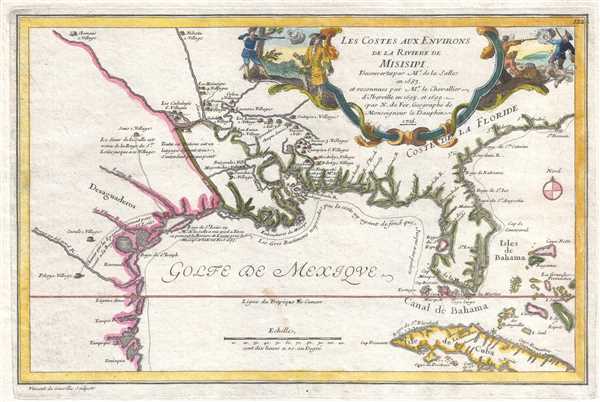

1705 De Fer Map of the Gulf Coast, Florida, Texas, and the Mississippi River

Misisipi2-defer-1705

Title

1705 (dated) 9 x 13.5 in (22.86 x 34.29 cm) 1 : 9000000

Description

De Fer is illustrating an ephemeral period in the colonization and mapping of North America between the 1688 destruction of La Salle's colony of Fort St. Louis (modern day Inez, Texas) and the consolidation of French power in the region through Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne Sieur de Bienville's 1717 founding of New Orleans. De Fer began drafting this map around 1699 during a period of great political sensitivity. Without a clearly declared heir, the death of King Carlos II of Spain, left a power vacuum in both Europe and the New World, and the French crown was strategically positioned to capitalize in both arenas.

Rene Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle, a French nobleman, explored the lower reaches of the Mississippi from the north, reaching the delta in 1682 (not, as the map's dedication here suggests, 1683). Recognizing the enormous profit potential in controlling the Mississippi River, thus linking French colonies in Canada with the Gulf of Mexico, La Salle returned to Europe to petition the King to build a settlement at the mouth of the river. Permission granted, he returned to the Gulf Coast to found Fort St. Louis. Unfortunately, La Salle was unable to rediscover the mouth of the Mississippi due to difficulties in measuring longitude as well as the inherently confusing nature of that coastline and instead founded his colony far west of its intended location. The fledgling colony, though plagued by mismanagement, disease, and hostile American Indians, only served to antagonize the Spanish. In response, the Spanish sent no less than three naval expeditions to map the Gulf Coast - much of the coastal cartography from these expeditions appears here. La Salle himself was murdered in 1687 by his own soldiers, who, unhappy with the failings of the colony, mutinied, a topic of considerable interest in Europe and the subject matter of this map's elaborate cartouche.

In 1698, the French crown commissioned another explorer, Canadian born Pierre le Moyne d'Iberville, to complete the work La Salle had begun. For the European elite of this period, the New World was more a concept than a reality. While many monarchs had dreams of vast New World empires, few had the resources and manpower to forge their dreams into a reality. Instead, claims were made based upon 'Right of Discovery' where knowledge of a region was tantamount to political occupation. In the case of the Gulf Coast, Spain had long claimed this territory, but had failed to occupy or properly reconnoiter it - a mistake the French were quick to capitalize on. By exploring inland and establishing clear maps and trade relations with local indigenous groups, the French Minister of Naval Affairs, Pontchartrain, recognized he could establish at least nominal control over much of North America. Thus, while this map ostensibly focuses on the explorations and death of La Salle, the cartography is primarily that of D'Iberville, a detail textually noted in the map's title.

The curious choice to emphasize La Salle's assassination and failure in the title cartouche may have been an attempt to draw attention away from the continued French explorations in Louisiana as personified by D'Iberville. The French at this time had every reason to want their Spanish neighbors happy, for Louis XIV's grandson, Philippe, Duc d'Anjou, was the primary claimant to the Spanish Crown. Until he was confirmed as King Felipe V of Spain, French powers needed to tread lightly with regard to any and all colonial rivalries.

D'Iberville's accomplishments include mapping some of the inland waterways and tributaries of the Mississippi River as well as making contact and establishing trade relations with various American Indian groups. He founded Fort Biloxi (in modern day Mississsippi) and Fort Maurepas (on the Mississippi River), both of which are identified here simply as 'Fort.' D'Iberville also founded a fort at Mobile, Alabama, which, though the Mobile River is noted, does not appear on this map, most likely because its 1701 founding postdated the composition of this map.

Quite few American Indian villages are labeled, including the Pascoboula, Chicaca, Quimpisa, Moctoby, and Biloky, all of which are on the Pascagoula River. Further west, on the opposite side of the Mississippi River, the combined Bojogoula (Bayogoula) and Majoutacha (Mougoulacha) villages are also noted. During the same time period as this map was being created, the Bayogoula were preparing for war against their neighbors. In 1700, they massacred both the Quinipissa and the Mougoulacha, as well as some of the smaller neighboring villages. This conflict was subsequently mediated by D'Iberville's brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, but the damage had already been done. A few years later, and just one year after this map was published, the Bayogoula themselves were massacred by the Tonica (Tunica), another much larger alliance of tribes noted here as residing somewhat further north along the Mississippi.

De Fer's work is often criticized for its decorative rather than scientific approach to cartography, especially when compared to the academic work of fellow 'Geographe du Roi' Guillaume de L'Isle. Nonetheless, he does introduce some new ideas and as the Dauphin's personal cartographer, De Fer had access to some of the most up to date cartographic information. This map is unique in that many of De Fer's actual manuscript originals and sample maps have survived, thus to some extent we are able to postulate on his thought process and study his sources. De Fer based this map on the 1698 map of the Gulf of Mexico by La Salle, a 1700 Map of the Gulf coast by Spanish navigator Juan Bisente, and an even earlier map also by Bisente dating to 1696. These he updated with data from D'Iberville's expeditions. The result is one of the earliest published maps to offer any real detail of the Lower Mississippi Valley. One very interesting departure from a convention being established in several previous late 18th century maps is De Fer's rejection of the 'Florida as Archipelago' hypothesis. Here Florida takes on a clear if distorted peninsular form that would also be embraced by De L'Isle later in the same year, 1701.

This map was drawn by De Fer between 1699 and 1701, engraved by Vincent de Ginville and published in De Fer's L'Atlas Curieux ou Le Monde.. We are aware of two states, 1701 and 1705. With the exception of the date, which has been updated for the 1705 edition, we have been unable to identify any cartographic changes between the two states.

Cartographer

Nicholas de Fer (1646 - October 25, 1720) was a French cartographer and publisher, the son of cartographer Antoine de Fer. He apprenticed with the Paris engraver Louis Spirinx, producing his first map, of the Canal du Midi, at 23. When his father died in June of 1673 he took over the family engraving business and established himself on Quai de L'Horloge, Paris, as an engraver, cartographer, and map publisher. De Fer was a prolific cartographer with over 600 maps and atlases to his credit. De Fer's work, though replete with geographical errors, earned a large following because of its considerable decorative appeal. In the late 17th century, De Fer's fame culminated in his appointment as Geographe de le Dauphin, a position that offered him unprecedented access to the most up to date cartographic information. This was a partner position to another simultaneously held by the more scientific geographer Guillaume De L'Isle, Premier Geograph de Roi. Despite very different cartographic approaches, De L'Isle and De Fer seem to have stepped carefully around one another and were rarely publicly at odds. Upon his death of old age in 1720, Nicolas was succeeded by two of his sons-in-law, who also happened to be brothers, Guillaume Danet (who had married his daughter Marguerite-Geneviève De Fer), and Jacques-François Bénard (Besnard) Danet (husband of Marie-Anne De Fer), and their heirs, who continued to publish under the De Fer imprint until about 1760. It is of note that part of the De Fer legacy also passed to the engraver Remi Rircher, who married De Fer's third daughter, but Richer had little interest in the business and sold his share to the Danet brothers in 1721. More by this mapmaker...