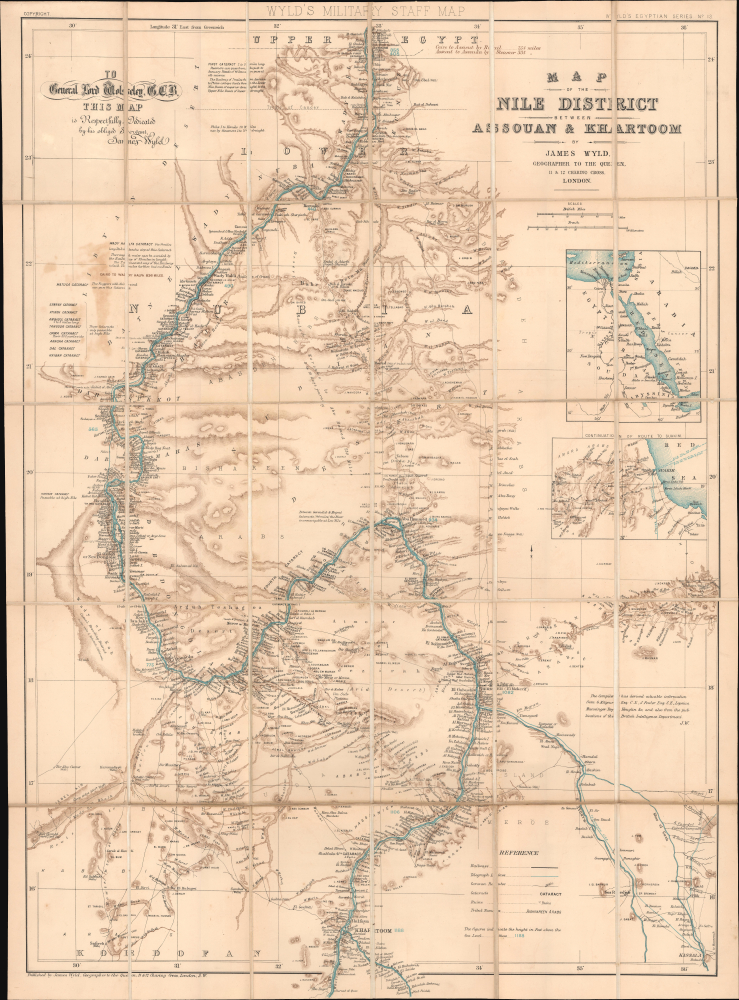

1885 Wyld Folding Map of the Nile River, Nile Expedition, Mahdist War

NileDistrict-wyld-1885

Title

1885 (undated) 34.5 x 25.5 in (87.63 x 64.77 cm) 1 : 1235000

Description

A Closer Look

The map covers the Nile River Delta from the First Cataract near Aswan (Assouan) to Khartoum, where the White Nile (Bahr al Abyad) and Blue Nile (Bahr al-Azraq) converge. A high level of detail is maintained throughout, including hundreds of settlements and historical ruins along the river and throughout the river delta, cataracts of the Nile, railway and telegraph lines, dry and seasonal riverbeds, caravan routes, wells, areas of elevation, and more. A wide range of supplementary information is included, such as the distance from Cairo to Aswan by rail and steamer, the ability (or lack thereof) of different types of boats to traverse the cataracts at different times (High Nile and Low Nile), railways that allow travelers to avert the cataracts, information on wells and sources of fresh water, and the camel breeding district of Wady el Kab managed by Kababish nomads. Blue numbers indicate the elevation of the river in feet above sea level, reaching a maximum of 1,188 at Khartoum.A small legend appears at the bottom towards the right, and Wyld's dedication to Wolseley is at the top left. An inset map at the right towards the top indicates the area covered by the map within the wider context of northeastern Africa. A second inset focuses on the area around the port of Suakin (Suakim), which strongly suggests that the map was printed in the late stages of or after the Nile Expedition, roughly in the second half of 1885.

The Mahdist War

This map is undated and only obliquely mentions conflict, but it was produced in the context of the Mahdist War, a massive religiously-inspired uprising against the rule of the British-backed Khedivate of Egypt beginning in 1881. The conflict was initially only one of many in the orbit of Britain's global empire, but it captured the public's imagination in 1884, when the charismatic adventurer-soldier Charles Gordon, acting beyond his orders from the British government, decided to defend Khartoum in a months-long siege, prompting the organization of a relief expedition.Charles George Gordon (1833 - 1885) was one of the more colorful and storied British imperial adventurers of the 19th century. Born to a family with a long line of British military service, he attended a military academy and then served in the Royal Engineers during the Crimean War with great distinction. Already at a young age, Gordon had a reputation for pluckiness and for disregarding orders, which would ultimately be his undoing.

Finding peacetime life uninteresting, Gordon volunteered to fight in China during the Second Opium War (1856-1860), which he arrived too late to participate in, instead finding work in Shanghai leading a multinational group of mercenaries known as the Ever Victorious Army against the rebels of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. He gained a reputation for honesty and effectiveness, imposing strict discipline on his mercenary force that was otherwise prone to plunder, rape, and corruption. Gordon was highly decorated by the Tongzhi Emperor and was praised by the foreign community in China, earning him the nickname 'Chinese Gordon.' At the same time, his frankness, such as criticizing Chinese officials to their faces and refusing monetary rewards from the emperor, was seen as uncouth and impudent.

After his service to the emperor in China, Gordon found employment with the Egyptian Khedive government, which appointed him as governor of their southern Equatoria province, over which they had only nominal control. Gordon was appalled by the Ottoman-Egyptian bureaucracy, which he found oppressive and corrupt, and the prevalence of the slave trade. (Gordon's abolitionism was inspired by his intense religiosity.) Nevertheless, his capabilities as an administrator and diplomat allowed him to rise to the position of Governor-General of the Sudan, earning him the new nickname of 'Gordon Pasha.' Still, Gordon eventually alienated other officials in the bureaucracy (several of whom he fired) to the point that he was asked not to continue in his position and left Egypt in 1880.

He then briefly worked as a bureaucrat in India before resigning, returning to China (against orders from the military), and agreeing to an administrative position in the Congo Free State. (He was an enthusiast for the project and its architect, King Leopold II, not foreseeing the horrific reality that would emerge there.) However, before he could begin work in the Congo, Gordon was called on by the British government to report on a large-scale rebellion that had broken out in Sudan in 1881 and was known as the Mahdist Uprising.

Given his prior experience in the region, Gordon was an obvious choice for such a mission, but his public statements about the uprising and his desire to see British military intervention made the government wary of sending him. It ultimately relented to public pressure, giving Gordon a mandate only to gather information and organize an orderly evacuation of Khartoum. Gordon indeed evacuated Khartoum of civilians but then 'went rogue' and attempted to defend the city, hoping to use it in the future as a base from which to subdue the Mahdist rebels. Initially, his position looked strong, as he had ample supplies, and the city was ideally suited for defense, surrounded by the Nile and rows of fortifications. Relying on friends in the press, Gordon continuously appealed to the British public to pressure the government to send a larger force to defend Khartoum.

By March 1884, Khartoum was completely cut off and surrounded by Mahdist troops. The Gladstone government was deeply opposed to any effort to relieve Gordon but, by August, had relented to public pressure and authorized a relief force led by General Garnet Wolseley, who, like Gordon, was very adept at using the press to rile up the public and pressure the government. Not wanting to send a regular force, the government enlisted French-Canadian voyageurs as private mercenaries, but by the time they arrived in Egypt and were prepared to travel by camel and steamship up the Nile, it was already October. Ascending the cataracts of the Nile (indicated here) was an especially difficult process and, along with skirmishes with Mahdist forces, delayed the expedition's progress by weeks. The relief force began to suffer exhaustion and casualties, including two of its leading officers, Herbert Stewart and William Earle.

The advance of the expedition was closely tracked in the British press. In the meantime, Gordon's force had been reduced by disease and skirmishes, and his supplies were running low. The relief force finally reached Khartoum on January 28, 1885, but the Mahdists had stormed the city two days earlier, captured it, and killed the entire garrison, including Gordon. The British public was incensed at the death of the popular Gordon and blamed Wolseley and the other leading officers of the relief expedition for delays, as well as the Gladstone government for its reluctance to send a relief force in the first place. Gordon was lionized as one of the great military heroes of his age. However, historians have subsequently debated his legacy, his psychology, and his significance as a public figure of the late Victorian era.

Concurrent with the Gordon Relief Expedition, a contingent was sent to clear a path to the Red Sea port of Suakin, clearing out Mahdist forces who controlled the lands between the Nile and the port. Following the fall of Khartoum, this group managed to win a series of battles against the rebels; however, soon afterward, the Gladstone government decided to abandon Suakin and the Sudan. The British returned several years later, crushed the Mahdists, and established a 'condominium' (effectively a protectorate) over Sudan.

Military Staff Maps

As a 'military staff map,' the present work was prepared for British military officers rather than the general public. Being dissected and laid on linen and folding into a cover allowed it to be larger (when unfolded), more robust, and more portable than other map formats, perfect for military officers in the field. As the 'geographer to the Queen,' who also specialized in making large and detailed folding maps, Wyld was the natural choice for producing these maps and was given privileged access to British intelligence to do so. As a result, Wyld's Military Staff Maps can be found for many of the key British military engagements of the late 19th century, from Egypt to South Africa to Afghanistan.Chromolithography

Chromolithography, sometimes called oleography, is a color lithographic technique developed in the mid-19th century. The process involved using multiple lithographic stones, one for each color, to yield a rich composite effect. Oftentimes, the process would start with a black base coat upon which subsequent colors were layered. Some chromolithographs used 30 or more separate lithographic stones to achieve the desired product. Chromolithograph color could also be effectively blended for even more dramatic results. The process became extremely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when it emerged as the dominant method of color printing. The vivid color chromolithography produced made it exceptionally effective for advertising and propaganda imagery.Publication History and Census

This map was prepared ('compiled') by James Wyld c. 1885 in the latter stages or soon after the Nile Expedition. Wyld indicates his sources at the right, towards the bottom, which include earlier French and Egyptian maps, as well as British intelligence reports. The present map is quite rare. Due to its being undated, it is cataloged variously as c. 1883 and c. 1888, but in any event, it is only noted among the holdings of six institutions in the OCLC: Stanford University, the Library of Congress, the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, and Stellenbosch University.Cartographer

Wyld (1823 - 1893) was a British publishing firm active throughout the 19th century. It was operated by James Wyld I (1790 - 1836) and his son James Wyld II (November 20, 1812 - 1887) were the principles of an English mapmaking dynasty active in London during much of the 19th century. The elder Wyld was a map publisher under William Faden (1749 - 1836) and did considerable work on the Ordinance Survey. On Faden's retirement in 1823, Wyld took over Faden's workshop, acquiring many of his plates. Wyld's work can often be distinguished from his son's maps through his imprint, which he signed as 'Successor to Faden'. Following in his father's footsteps, the younger Wyld joined the Royal Geographical Society in 1830 at the tender age of 18. When his father died in 1836, James Wyld II was prepared to fully take over and expand his father's considerable cartographic enterprise. Like his father and Faden, Wyld II held the title of official Geographer to the Crown, in this case, Queen Victoria. In 1852, he moved operations from William Faden's old office at Charing Cross East (1837 - 1852) to a new, larger space at 475 Strand. Wyld II also chose to remove Faden's name from all of his updated map plates. Wyld II continued to update and republish both his father's work and the work of William Faden well into the late 1880s. One of Wyld's most eccentric and notable achievements is his 1851 construction of a globe 19 meters (60 feet) in diameter in the heart of Leicester Square, London. In the 1840s, Wyld also embarked upon a political career, being elected to parliament in 1847 and again in 1857. He died in 1887 following a prolific and distinguished career. After Wyld II's death, the family business was briefly taken over by James John Cooper Wyld (1844 - 1907), his son, who ran it from 1887 to 1893 before selling the business to Edward Stanford. All three Wylds are notable for producing, in addition to their atlas maps, short-run maps expounding upon important historical events - illustrating history as it was happening - among them are maps related to the California Gold Rush, the New South Wales Gold Rush, the Scramble for Africa, the Oregon Question, and more. More by this mapmaker...