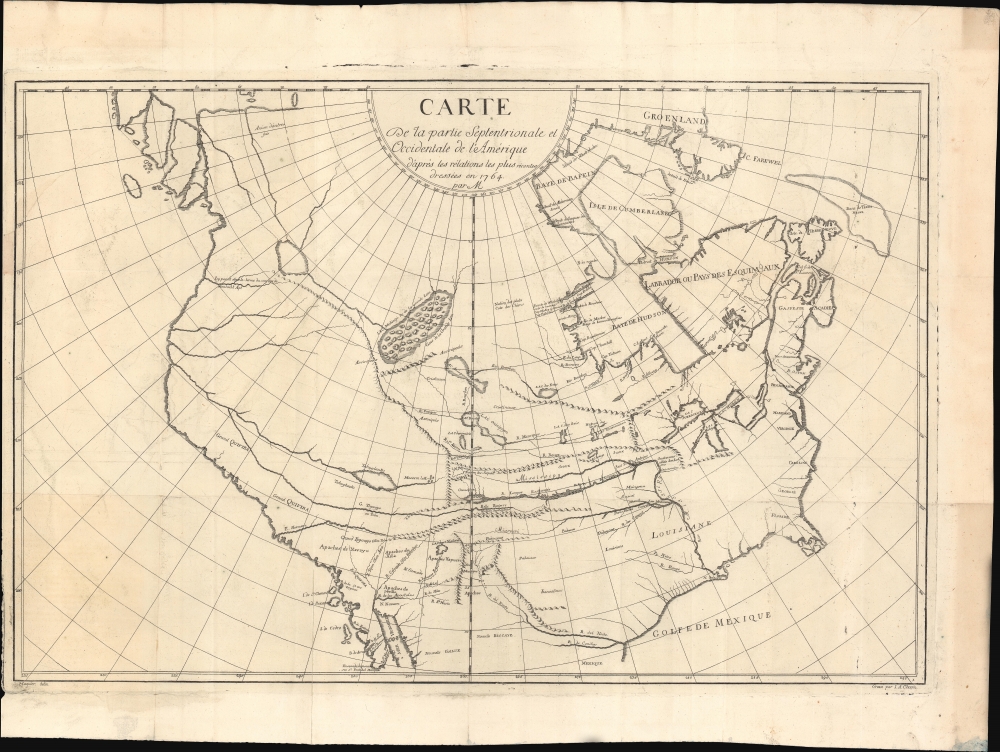

1765 Engel Map of North America (speculative)

NorthAmerica-engel-1764-2

Title

1764 (undated) 20 x 30 in (50.8 x 76.2 cm) 1 : 9600000

Description

Addressing the Buache-Delisle, Müller-Bering Controversy

Engel composed this map to illustrate his attempt to reconcile and correct the cartography that emerged from the Buache-Delisle, Müller-Bering controversy over the geography of the North Pacific and the Pacific Northwest. As described by Lada-Mocarski, Engelexamined diligently the maps and writings of Kirilov (the compiler of the first Russian atlas), Buache, Delisle, Müller, Gmelin, and others - and invariably, with some justification, found something wrong with each of them. He examined these works with regard to the northern parts of both Asia and America. Most of the questions he raised were valid and the present-day student of these regions would profit by reading his work with modern maps before him, to see who was right or wrong - and when wrong, how wrong. A valuable part of Engel's present work is his rejection of the persistent belief held by many of his contemporary geographers and cartographers that California was an island. He unequivocally asserted... that (in translation), 'California is not an island but a peninsula. (Lada-Mocarski, V., Bibliography of Books on Alaska Published before 1868).

Importat Source Map

This important map provides the source material for Denis Diderot and Robert de Vaugondy's important speculative map of North America. The Diderot/Vaugondy map was published as part of a 10-map supplement to Diderot's popular Encyclopedie intended to explore positivist speculation on the still unknown cartography of western North America. While the latter and much smaller Diderot/Vaugondy map is reasonably common, this, its source map, is far more significant and rarely appears on the market. The scarcity of this map can be illustrated most plainly by the fact that, despite its importance, this map is not identified in Wheat's Transmississippi West (the derivative 1771 Vaugondy/Diderot Map is included).Scope of the Map

Engel's map covers North America from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Circle and from the Grand Banks to a proto-Alaskan archipelago. It is presented on an equidistant cylindrical projection, possibly on the c. 1745 Cassini-Soldner model. Engel's map consolidates numerous cartographic theories, reports from voyages both dubious and factual, and established conventions into a sophisticated examination of the general layout of waterways - especially in the American West.Engel is cautious to not specifically illustrate an Atlantic-Pacific water connection, while at the same time leaving open the possibility. Rivers and lakes extend from the eastern part of the continent almost, but never quite meet their western counterparts. Six largely mythical river systems extend inland from the unlabeled Pacific. Several meet with enormous and interesting apocryphal lakes, including Lac Michinipi, Lac Tahuglauks, and an unlabeled lake that Robert de Vaugondy, in his derivative map, associates with the mythical Lake Conibas.

Great Salt Lake

Through error or luck, it is interesting to observe not only where Engel went wrong but also where he was right. The southernmost of the several great western lakes identified here is Lake Tahuglauks, situated essentially where the Great Salt Lake actually exists.The Legacy of Lahonton

The cartographer here references the dubious explorations of Baron Louis Armand de Lahonton (1666 - 1715). Lahonton was a French military officer commanding the fort of St. Joseph near modern-day Port Huron, Michigan. Abandoning his post to live and travel with local Chippewa, Lahonton claims to have explored much of the Upper Mississippi Valley and even discovered a heretofore unknown river, which he dubbed the 'Longue River.' We can see this river extending westward from the Mississippi near the Falls of St. Antoine (St. Anthony Falls, modern-day Minneapolis). He claims to have followed this river a good distance from its convergence with the Mississippi.Beyond the point where he himself traveled, Lahonton wrote of further lands along the river described by his Native American guides. These include a great saline lake or sea at the base of a mountain range. This range, he reported, could be easily crossed, from which further rivers would lead to the mysterious lands of the Mozeemleck, and presumably the Pacific. By incorporating Lahonton's mountains, Engel effectively puts in place the Rocky Mountains. Various scholars both dismissed Lahonton's work as fantasy and defended it as speculation. Could Lahonton have been describing indigenous reports of the Great Salt Lake? What river was he on? Perhaps we will never know.

What we do know is that on his return to Europe, Lahonton published his travels in a popular book. Lahonton's work inspired many important cartographers of his day: Engel, Moll, De L'Isle, Popple, Sanson, and Chatelain, to name just a few, to include on their maps both the Longue River and the saline sea beyond. The concept of an inland river passage to the Pacific fired the imagination of the French and English, who were aggressively searching for just such a route. Unlike the Spanish, who had easy access to the Pacific through the Mexican port of Acapulco, the French and English had no easy route by which to offer their furs and other commodities to the affluent markets of Asia. A passage such as Lahonton suggested was just what was needed. More than any factual exploration, wishful thinking fueled the inclusion of Lahonton's speculations on so many maps.

Moncacht-Apé

Engel also incorporates information from the voyages of the Yazoo explorer Moncacht-Apé. Moncacht-Apé accomplished the first recorded roundtrip transcontinental journey across North America. His descriptions provided Europeans with the first first-hand report of the Columbia River. In fact, from Moncacht-Apé 's reports, Engel here maps the Columbia River as 'Icy paroit etres le terme du voyage de Moncacht-Apé ' - most likely the first mapping of the Columbia River on any western map.Moncacht-Apé's epic journey most likely took place in the late 17th century. The tale was later passed on to Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, a French explorer and ethnographer in Louisiana. Moncacht-Apé met Le Page near Natchez sometime before 1729 and recounted his fantastic voyage, which Le Page published in 1753. Unlike the voyages Lahonton, most scholars consider the Moncacht-Apé exploration to be factual, though possibly embellished. Two factors contribute to this. First, the Moncacht-Apé tale includes none of the speculative geography common to European mapping of the American West. Second, Le Page's account, while the largest and most thorough, is not the only account of Moncacht-Apé. Other known persons, most notably the French officer Jean-Francois-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, also referred to this voyage and met Moncacht-Apé.

Mysterious Arctic Lakes

The map includes several large inland lakes, among them the large and striking island-filled Lac Michinipi and a smaller unnamed connected lake to the west. Engel's source material for both is unclear. Michinipi may have some relation to the c. 1730 explorations of the French fur trappers La Verendrye and Nicolas Jeremie. Some suggest this may have been an early account of Reindeer Lake or simply an attempt to map the densely watered region to the northwest of Winnipeg. Later cartographers associate Michinipi with Lake Assiniboine, though here Engel makes them two separate lakes. Verendrye and Jeremie traveled the rivers and lakes between Lake Winnipeg and the Hudson Bay, as well as the connections to other lakes further north. The larger lake further to the west is something of a mystery, as are its connections to large northern river systems. Robert de Vaugondy, in his map issued five years later, associated this with the mysterious and speculative 16th-century Lake Conibas.Indigenous Empires and Cities of Gold

Engel makes only a few notes regarding the indigenous peoples of the region. He identifies three mythical kingdoms of the west: Gran Teguaio (Teguayo, also Tolm), Grand Quivara, and Anian. Quivara was initially a civilization sought by the conquistador Coronado in the Great Plains near the Mississippi. Cartographers steadily moved Quivara further and further west until, as here, it appears in California.Teguayo was believed to be one of the seven Kingdoms of Gold presumably to be discovered in the unexplored American West. The name Teguayo first appears in the Benevides Memorial, where it is described as a kingdom of great wealth to rival Quivara. The idea was later popularized in Europe by the nefarious Spanish conman and deposed governor of New Mexico, the supposed Count of Penalosa, who, imagining himself a later-day Pizzaro, promoted the Teguayo legend to the royalty of Europe. Originally, Teguayo was said to lie west of the Mississippi and north of the Gulf of Mexico, but, for some reason, Engel situates it far to the west.

Far to the north on the Arctic coast, north of proto-Alaska, Engel identifies the Land of Anian. The first mention of Anian appears in Marco Polo's narratives, which describe it as 'a place to the east of India.' In this case, India is not the subcontinent but rather a term that refers to Farthest Asia. Since the time of Mercator, this term has been associated with the extreme northwest of America and a possible straight or even land connection with Asia.

Proto-Alaska

Engel further offers a unique treatment of the lands to the west of Anian that we have earlier described as a 'Proto-Alaska.' Kershaw considers Engel's cartography derivative of Gerhard Friedrich Müller's (1705 - 1783) map of 1754. Muller, a historian and cartographer employed by the Russian Academy of Sciences, published a map based on actual Russian discoveries in refutation of the more popular speculative Delisle / Buache maps of the same. Muller identifies several of Bering's documented sightings of land either on the Alaskan peninsula itself or the Aleutian Islands. These he connected to form the speculative Muller Peninsula. Here, Engel takes the idea a step further by turning each sighting of land into an independent island with navigable watercourses in between - thus more closely resembling the actual Aleutian Archipelago. The reasoning behind this is unclear, but it may have to do with wishful thinking that his Lake Michinipi, which he connects to Anian via riverways, may, in fact, be a route west via the Lake Winnipeg network to the Columbia River.Publication History and Census

This map was drawn in 1764 for Engel by M. Jaquier and engraved by Jacques (Iacabo) Anthony Chovin in Paris for publication in his 1765 Memoires et Observations Geographiques et Critiques. There are two variants. One signed 'M. Jaquier' and the other signed 'Maquier'. The variants also differ in that the first has 'par M***' in the title, while the other has 'Par M' (present example). There is at least one variant where, to the north of the Tajuglauks territory, a note reads 'Alliés of the Sioux', but there is no clear primacy. We note no other differences between the plates. The map is represented in perhaps 6 collections in the OCLC. Scarce to the market.CartographerS

Samuel Engel (1702 - 1784) was a Swiss geographer, agronomist, and mathematician active in the middle part of the 18th century. His main work, Memoires and Observations was published in 1765 and while somewhat obscure today was highly influential in the 1700s. Engel argued that ice only formed in fresh water and that, such being the case, the Arctic Ocean would be ice-free and navigable closer to the poles. Engel's theories influenced exploration in search of the Northwest Passage, and specifically the launching of the disastrous 1773 Phipps expedition to the North Pole. He also wrote several articles for Diderot's Encyclopedie, including a description of a pre-Columbian Chinese colony in North America - Fusang. Engel also argued that Baron Lahonton, an enigmatic explorer of America's inland waterways, was in fact fictitious - though he nonetheless incorporated Lahonton's geography in his own maps. More by this mapmaker...

Jacques Anthony Chovin (1720 - 1776) was a Swiss-French engraver active in the mid to late 18th century. Chovin was born in Lausanne, Switzerland. It is unlcear where he was trained, but Chovin was an engraver of exceptional skill. He is best known for the dramatic engraving the 1744 edition of Mathieu Mérian's Der Basler Totentanz ('The Basel Dance of Death'). He engraved several maps for the swiss geographer Samuel Engel (1702 - 1784). He often signed his works 'I. A. Chovin.' Learn More...