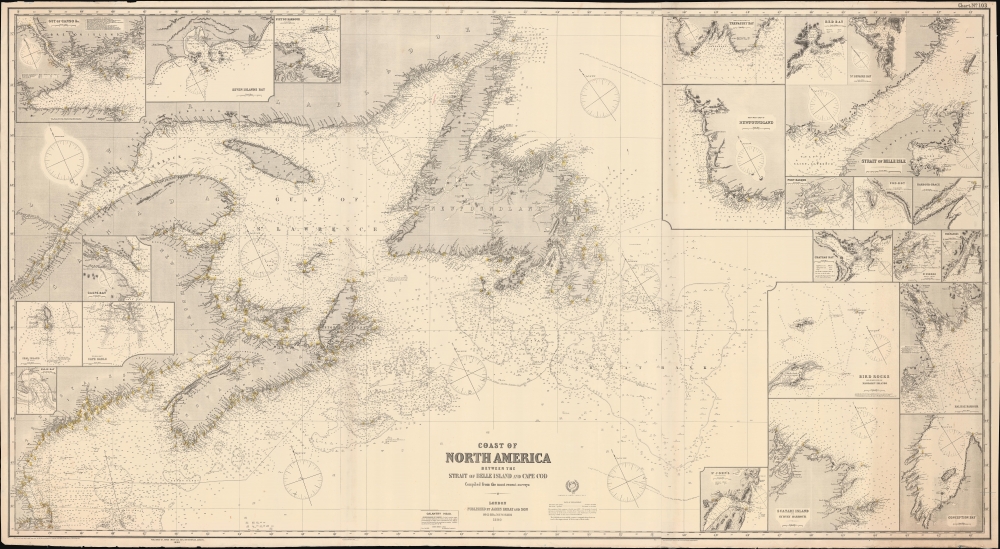

1890 Imray Chart of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and New England

NovaScotiaNewfoundland-imray-1890

Title

1890 (dated) 41 x 74.75 in (104.14 x 189.865 cm) 1 : 1584000

Description

A Closer Look

Coverage ranges from the Saint Lewis Sound just north of Belle Isle southwards to Buzzards Bay and Nantucket Sound. Soundings, currents, shoals, reefs, hazards, anchorages, lighthouses (surrounded by circles indicating the range of their light), magnetic variations, and other features are recorded at an astounding level of detail. Fully twenty-three insets appear, including close-ups of the Strait of Belle Isle, Halifax Harbour, and St. John's (Newfoundland). Also significant are jagged lines at right illustrating the extent of ice in different parts of the year.Imray and Son were renowned for their dedication to providing the most comprehensive and up-to-date information possible, which explains the box below and to the left of the table on the closure of the Galantry Head Lighthouse and a note in red about a lighthouse destroyed in Ingornachoix Bay. The bottom margin notes a rapid succession of corrections, often several in a single year.

The Direct United States Telegraph Cable

One notable feature is the 'Direct United States Telegraph Cable,' completed in 1874, which connected Ballinskelligs, Ireland to Tor Bay, Nova Scotia, and then connected Tor Bay to Rye, New Hampshire. The line's name was derived from the fact that it linked directly to the U.S. (albeit after a stopover in Nova Scotia), whereas previous Transatlantic lines only used underwater cables to Newfoundland, then a shorter cable to Nova Scotia, after which they connected to overland networks. However, the company was immediately embroiled in controversy. The U.S. Congress had stipulated that it remain independent and not collaborate with competing lines, but accusations quickly arose that it was effectively a wing of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph, which itself had become an instrument of Jay Gould's attempt to gain a larger share of (critics would say monopolize) telegraph communications in the U.S.Blueback Charts

Blueback nautical charts began appearing in London in the late 18th century. Bluebacks, as they came to be called, were privately published large format nautical charts known for their distinctive blue paper backing. The backing, a commonly available blue manila paper traditionally used by publishers to wrap unbound pamphlets, was adopted as a practical way to reinforce the low-quality paper used by private chart publishers in an effort to cut costs. That being said, not all blueback charts are literally backed with blue paper. The earliest known blueback charts include a 1760 chart issued by Mount and Page, and a 1787 chart issued by Robert Sayer.The tradition took off in the early 19th century, when British publishers like John Hamilton Moore, Robert Blachford, James Imray, William Heather, John William Norie, Charles Wilson, David Steel, R. H. Laurie, and John Hobbs, among others, rose to dominate the chart trade. Bluebacks became so popular that the convention was embraced by chartmakers outside of England, including Americans Edmund March Blunt and George Eldridge, as well as Scandinavian, French, German, Russian, and Spanish chartmakers. Blueback charts remained popular until the late 19th century, when government subsidized organizations like the British Admiralty Hydrographic Office and the United States Coast Survey began issuing their own superior charts on high quality paper that did not require reinforcement.

Publication History and Census

This chart was published by James Imray and Son in 1890. The only example of this map noted in the OCLC is held by the National Library of Wales and dated to 1850. The Library and Archives Canada also hold examples of editions from 1863, 1865, and 1876. Imray's chart appears to have been strongly influenced by John Stratton Hobbs similarly titled 1848 chart 'A Chart of the Coast of North America, from the Strait of Belle Isle to Boston including the Banks and Island of Newfoundland, The Gulf and River of St. Lawrence, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc.' (previously sold by us). A comparison of Hobbs' 1848 chart, very impressive for its time, and earlier editions of Imray's chart with the present example demonstrate advances in hydrography, especially the coverage of soundings, as well as the proliferation of lighthouses along the coast.Cartographer

James Imray (May 16, 1803 - November 15, 1870) was a Scottish hydrographer and stationer active in London during the middle to latter part of the 19th century. Imray is best known as a the largest and most prominent producer of blue-back charts, a kind of nautical chart popular from about 1750 to 1920 and named for its distinctive blue paper backing (although not all charts that may be called "blue-backs" actually have a blue backing). Unlike government charts issued by the British Admiralty, U.S. Coast Survey, and other similar organizations, Imray's charts were a private profit based venture and not generally the result of unique survey work. Rather, Imray's charts were judicious and beautiful composites based upon pre-existing charts (some dating to the 17th century) and new information gleaned from governmental as well as commercial pilots and navigators. Imray was born in Spitalfields, England, the eldest son of a Jacobite dyer also named James. Imray did not follow his father profession, instead apprenticing to William Lukyn, a stationer. He established himself as a bookseller and bookbinder at 116 Minories Street, where he shared offices with the nautical chart publisher Robert Blanchford. In 1836 Imray signed on as a full partner in Blanchford's enterprise, christening themselves Blanchford & Imray. At this time the Blanchford firm lagged far behind competing chart publishers Norie and Laruie, nevertheless, with the injection of Imray's marketing savvy the firm began a long rise. James Imray bought out Blanchford's share in 1846, becoming the sole proprietor of the chart house, publishing under the imprint of James Imray. Relocating in 1850 to larger offices at 102 Minories, Imray was well on track to become the most prominent chart publisher in London. In 1854, when Imray's 25 year old son, James Frederick Imray, joined as a full partner, the firm again changed its imprint, this time to James Imray and Son. The elder Imray was a master of marketing and was quick to respond to trade shifts and historic events. Many of his most successful charts were targeted to specific trade routes, for example, he issued charts entitled "Cotton Ports of Georgia" and "Rice Ports of India". Other charts emerged quickly following such events as the 1849 California Gold Rush. Imray's rise also coincided with the development of governmental mapping organizations such as the Admiralty and the U.S. Coast Survey, whose work he appropriated and rebranded in practical format familiar to navigators. Imray's death in 1870 marked a major transition in the firm's output and began its decline. Though Imray's son, James Frederick, excelled at authoring pilot books he had little experience with charts and issued few new publications. Most James Frederick Imray publications issued from 1870 to 1899 were either revisions of earlier maps prepared by his father or copies of British Admiralty charts. Charts from this period are recognizable as being less decorative than the elder Imray's charts following the stylistic conventions established by the Admiralty. The Admiralty itself at the same time began to rise in prominence, issuing its own official charts that were both cheaper and more up to date than those offered by private enterprises. By the end of the century the firm was well in decline and, in 1899 "James Imray and Son" amalgamated with the similarly suffering "Norie and Wilson", which was itself acquired by Laurie in 1904. Today it continues to publish maritime charts as "Imray, Laurie, Norie and Wilson". More by this mapmaker...