This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

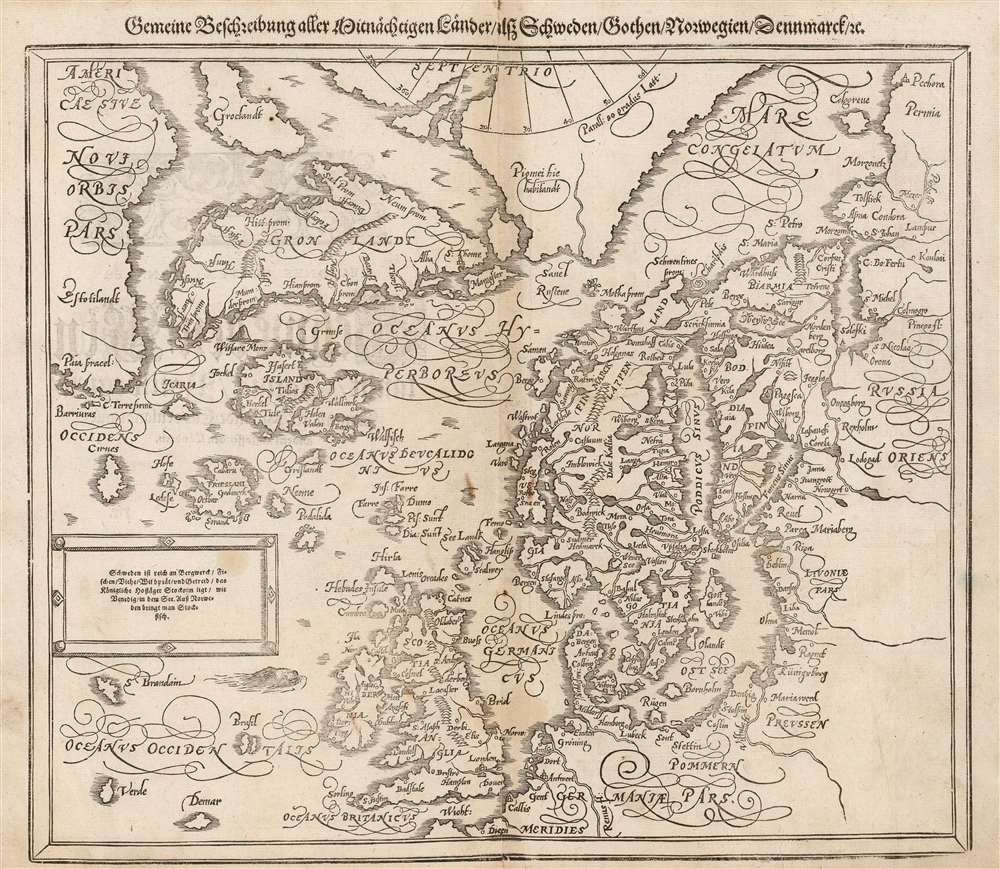

1588 Munster Woodcut View of Scandinavia, the North Atlantic, and Arctic Regions

Scandinavia-munster-1588

Title

1588 (undated) 12.75 x 14.25 in (32.385 x 36.195 cm) 1 : 10000000

Description

The Source

Ortelius' 1570 map of Scandinavia and the Arctic was and is one of his most fascinating maps; during the Age of Discovery, these north parts of the world represented regions as remote and unfamiliar as the coasts of America, Africa, and Asia. The map covers the northern regions from the English Channel to the just south of the North Pole and from America to Russia, including England, Scandinavia, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, and Greenland, as well as parts of America (Estotiland), the apocryphal island of Frisland, and Mercator's speculative Arctic islands.Ortelius's Sources

Just as Münster was before him, Ortelius was an apt compiler and editor, synthesizing the best sources that he could locate. As Münster did, Ortelius drew upon the 1539 Olaus Magnus Carta marina for the general forms of Scandinavia and Iceland. Ortelius' map, however, had a broader scope and tapped sources not available during Münster's lifetime. Nicolo Zeno's 1561 Septentrionalium Partium Nova Tabula provided images of Estotiland, Iceland, Greenland, Icaria, and Frisland; Anthony Jenkinson's 1562 map of Russia, and Gerard Mercator's world maps of 1564 and 1569 for the high Arctic inform those coasts both on Ortelius' original, and this map produced for Petri.Zeno's Spurious yet Tenacious Geography

This is one of the few maps to depict Estotiland and Droegeo, both drawn from the narrative of the Zeno brothers, supposedly written in the 14th century, before Columbus, but actually published in 1561 as a deliberate fraud by the Venetian merchant and statesman Nicolo Zeno. Most subsequent cartographers associated Estotiland with Labrador based upon Zeno's description,… the fishing vessel 'Frise' was blown westward by a storm, and arrived at a land named 'Estotiland,' whose inhabitants traded with 'Engroenelandt.' This country, 'Estotiland,' was very fertile, and had mountains inland. The king of this country possessed books written in Latin, which he did not understand. The language that he spoke and his subjects shared no similarity to that of the Vikings. The king of Estotiland, seeing that his guests sailed safely with the aid of an instrument (the compass), persuaded them to make a maritime expedition to another land to the south called 'Drogeo.'Also prominent are Zeno's imaginary islands of Icaria and Frisland. As with Estotiland, Zeno credited his 14th century predecessors with the discovery of these mysterious islands which appeared first on his own 1561 map, and which were eagerly copied by later mapmakers thirsty for geographical data on this remote part of the world. Despite Zeno's work being a fraudulent Venetian attempt to co-opt the achievements of the Genoese Christopher Columbus, it remained influential in the 16th and 17th centuries absent better cartographic reconnaissance of the North Atlantic. Not only Ortelius, but his competitor De Jode, and the Dutch mapmakers of the early 17th century embraced the Zeno geography.

Mercator's Arctic Islands

This remains one of the earliest maps to illustrate Gerard Mercator's speculative Arctic Islands. When Mercator published his great wall map introducing the famous Mercator Projection in 1569, he recognized the essential problem with his map was that it massively distorted the polar regions. To rectify this, he included a polar projection as in inset on the map. It was this small projection, later refined in his 1595 Arctic map, that introduced Mercator's idea of four arctic islands surrounding an open Arctic Sea, at the center of which was a great whirlpool. Two of those islands are visible here, one unnamed, and the other just north of Norway, labeled Pigmei hic habitant, for Mercator's assertion that it was the home of a race of female pygmies. The channel between the islands, possibly Mercator's interpretation of Davis Strait, was described as having violent currents. Variants on Mercator's Arctic islands continued to appear in various forms well into the 17th century, until the discoveries of Spitzbergen and other factual Arctic islands began to intrude upon the speculation. The islands disappeared entirely in Hondius's 1636 Arctic map Poli Arctici et Circumiacentium Terrarum Descriptio Novissima. So as derivative as the Petri/Münster map may have been, it remained representative of the best geographical knowledge of the north parts of the world well into the seventeenth century.Publication History and Census

This map was among the newly-produced woodcut maps added to the German edition of Cosmographia in 1588 by Sebastian Petri, who had inherited the print shop from his father Heinrich Petri. It remained in the subsequent editions without material change. The present example conforms typographically to the map found in the 1588 German edition of the book. The German and Latin editions of Cosmographia are well represented in institutional collections. Various editions of the separate map are listed in OCLC by six libraries. The map appears on the market from time to time.CartographerS

Sebastian Münster (January 20, 1488 - May 26, 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, Hebrew scholar and humanist. He was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518, after which he was appointed to the University of Basel in 1527. As Professor of Hebrew, he edited the Hebrew Bible, accompanied by a Latin translation. In 1540 he published a Latin edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, which presented the ancient cartographer's 2nd century geographical data supplemented systematically with maps of the modern world. This was followed by what can be considered his principal work, the Cosmographia. First issued in 1544, this was the earliest German description of the modern world. It would become the go-to book for any literate layperson who wished to know about anywhere that was further than a day's journey from home. In preparation for his work on Cosmographia, Münster reached out to humanists around Europe and especially within the Holy Roman Empire, enlisting colleagues to provide him with up-to-date maps and views of their countries and cities, with the result that the book contains a disproportionate number of maps providing the first modern depictions of the areas they depict. Münster, as a religious man, was not producing a travel guide. Just as his work in ancient languages was intended to provide his students with as direct a connection as possible to scriptural revelation, his object in producing Cosmographia was to provide the reader with a description of all of creation: a further means of gaining revelation. The book, unsurprisingly, proved popular and was reissued in numerous editions and languages including Latin, French, Italian, and Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Münster's death of the plague in 1552. Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, passing through 24 editions between 1544 and 1628. This success was due in part to its fascinating woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). Münster's work was highly influential in reviving classical geography in 16th century Europe, and providing the intellectual foundations for the production of later compilations of cartographic work, such as Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Münster's output includes a small format 1536 map of Europe; the 1532 Grynaeus map of the world is also attributed to him. His non-geographical output includes Dictionarium trilingue in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and his 1537 Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Most of Munster's work was published by his stepson, Heinrich Petri (Henricus Petrus), and his son Sebastian Henric Petri. More by this mapmaker...

Heinrich Petri (1508 - 1579) and his son Sebastian Henric Petri (1545 – 1627) were printers based in Basel, Switzerland. Heinrich was the son of the printer Adam Petri and Anna Selber. After Adam died in 1527, Anna married the humanist and geographer Sebastian Münster - one of Adam's collaborators. Sebastian contracted his stepson, Henricus Petri (Petrus), to print editions of his wildly popular Cosmographia. Later Petri, brought his son, Sebastian Henric Petri, into the family business. Their firm was known as the Officina Henricpetrina. In addition to the Cosmographia, they also published a number of other seminal works including the 1566 second edition of Nicolaus Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium and Georg Joachim Rheticus's Narratio. Learn More...