1937 Look Pictorial View of San Francisco's Chinatown

SFChinatown-look-1937$250.00

Title

High-Spots of San Francisco Chinatown.

1937 (dated) 5.25 x 12 in (13.335 x 30.48 cm)

1937 (dated) 5.25 x 12 in (13.335 x 30.48 cm)

Description

This is a scarce 1937 promotional pamphlet for San Francisco's Chinatown. Geared towards tourists, it demonstrates the changing perceptions of Chinatown from a place of crime and disease to a tourist destination in the wake of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire.

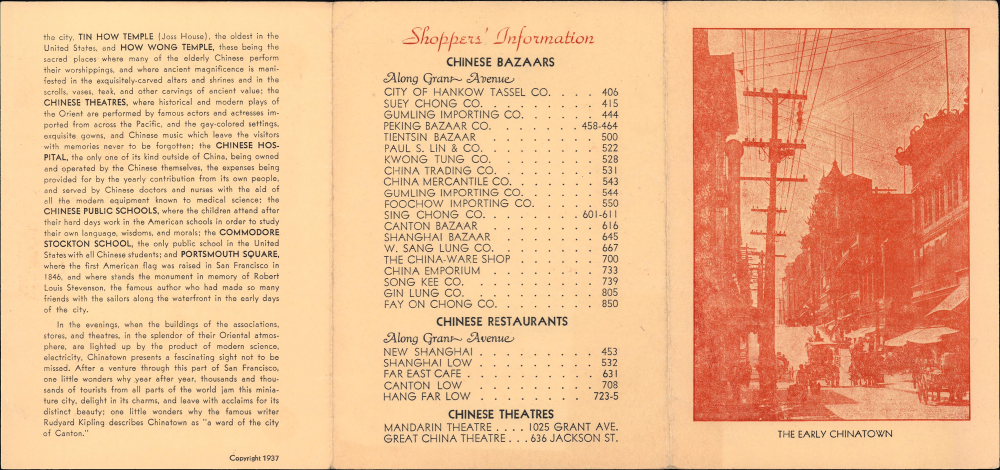

For many years prior, Chinatown was denigrated as a den of vice, crime, disease, and poverty. Yet, these same characteristics also brought in curious members of the non-Chinese community, including clients to the area's brothels and tourists. Tour guides did all they could to play up the area's licentiousness and even staged incidents to highlight Chinatown's 'depravity.'

As the largest Chinatown in America and probably anywhere in the world at the time, San Francisco's Chinatown was ground zero for racist attacks, including a deadly race riot in 1877. In the immediate aftermath of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, a city committee was formed to consider rebuilding the neighborhood elsewhere, with its prime location being considered too valuable to leave to the Chinese (ironically, this effort failed in part because of racial housing covenants in most other parts of the Bay Area left no alternative location for the Chinese).

Instead, Chinatown was rebuilt with brick, its mostly wooden structures having gone up in the fire (the brick Old St. Mary's Church being one of the most prominent survivors of the conflagration). Several prominent buildings, highlighted here, were also built in a style that played into a stereotyped view of 'Oriental' architecture, with pagoda roofs, in an effort to attract tourists. Organized crime, gambling, and prostitution were also cracked down on, with the blessing of the Six Companies, which was long-established as the de facto representative body of Chinatown. Although the increased tourism to Chinatown did not necessarily improve the material situation of the people living there, where poverty and overcrowding remained major problems, it did help to blunt the intense anti-Chinese racism prevalent in the late 19th century and elevated the neighborhood to an indelible part of San Francisco's identity in the eyes of White America. In brief, the same difference that had made Chinatown a target in earlier years made it an attraction in the early decades of the 20th century.

A Closer Look

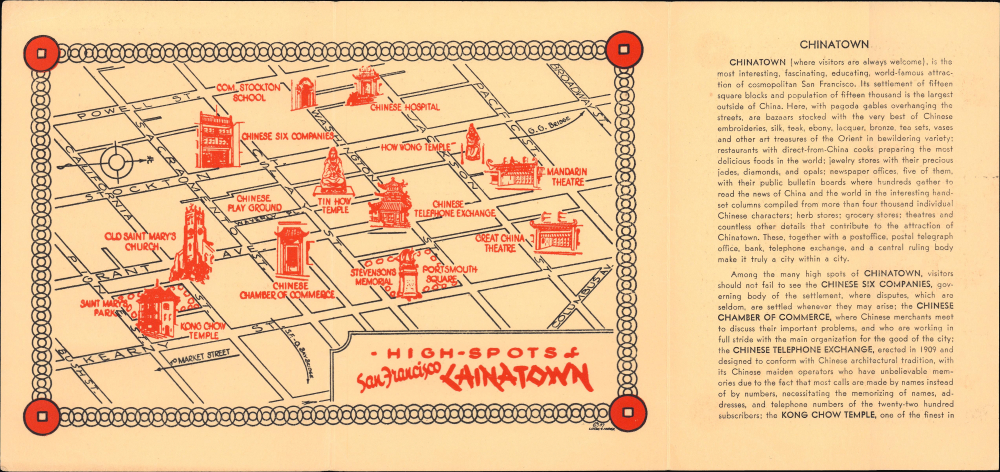

This map is oriented roughly towards the west, covering the area between Powell St. and Kearny St. on an east-west axis, and between Pacific St. (now Ave.) and Bush St. on a north-south axis. Several prominent local buildings and landmarks are illustrated and labelled, including Portsmouth Square, the Chinese Six Companies, and several temples and theaters (all still standing, though the Mandarin Theater building no longer operates as such). Promotional text at right and on the verso describes these attractions and Chinatown more generally.Chinatown Tourism

The tone of this map and associated text is notable. At a time when the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect (not repealed until 1943) and open racism against Asian-Americans was commonplace (as with racial housing covenants), here, San Francisco's Chinatown is presented as an exotic, enticing tourist destination. This was no accident but the result of a deliberately crafted image produced in the wake of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire by leading members of San Francisco's Chinese community and the city's political leadership.For many years prior, Chinatown was denigrated as a den of vice, crime, disease, and poverty. Yet, these same characteristics also brought in curious members of the non-Chinese community, including clients to the area's brothels and tourists. Tour guides did all they could to play up the area's licentiousness and even staged incidents to highlight Chinatown's 'depravity.'

As the largest Chinatown in America and probably anywhere in the world at the time, San Francisco's Chinatown was ground zero for racist attacks, including a deadly race riot in 1877. In the immediate aftermath of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, a city committee was formed to consider rebuilding the neighborhood elsewhere, with its prime location being considered too valuable to leave to the Chinese (ironically, this effort failed in part because of racial housing covenants in most other parts of the Bay Area left no alternative location for the Chinese).

Instead, Chinatown was rebuilt with brick, its mostly wooden structures having gone up in the fire (the brick Old St. Mary's Church being one of the most prominent survivors of the conflagration). Several prominent buildings, highlighted here, were also built in a style that played into a stereotyped view of 'Oriental' architecture, with pagoda roofs, in an effort to attract tourists. Organized crime, gambling, and prostitution were also cracked down on, with the blessing of the Six Companies, which was long-established as the de facto representative body of Chinatown. Although the increased tourism to Chinatown did not necessarily improve the material situation of the people living there, where poverty and overcrowding remained major problems, it did help to blunt the intense anti-Chinese racism prevalent in the late 19th century and elevated the neighborhood to an indelible part of San Francisco's identity in the eyes of White America. In brief, the same difference that had made Chinatown a target in earlier years made it an attraction in the early decades of the 20th century.

Publication History and Census

This map and pamphlet were produced in 1937 by a printer whose name, in the bottom-right margin of the map, is not entirely legible (Look and?). We have been unable to locate any other examples of this pamphlet in institutional collections or on the market.Condition

Very good. Light wear along original fold lines.

References

Rast, R., 'The Cultural Politics of Tourism in San Francisco's Chinatown, 1882-1917' Pacific Historical Review, 76 (1) 2007, pp. 29 - 60.