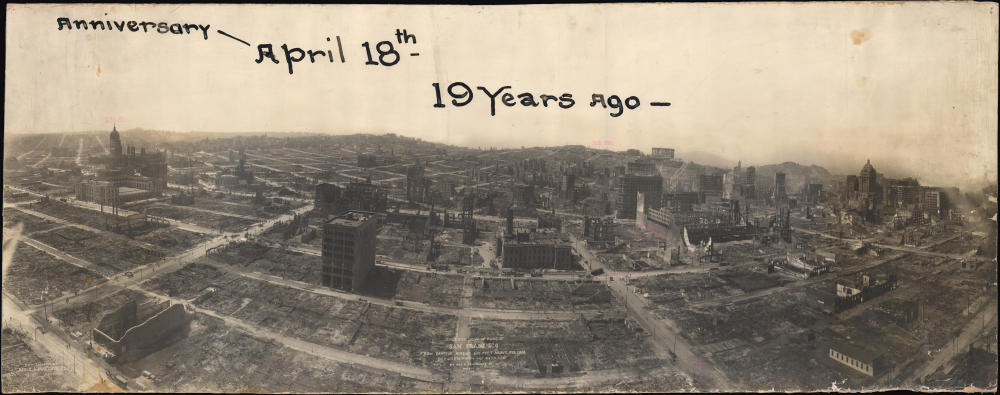

1906 Lawrence Panoramic Photograph of San Francisco, Earthquake and Fire Ruins

SFRuins-lawrence-1906

Title

1906 (undated) 17.75 x 45.25 in (45.085 x 114.935 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

The view is oriented towards the northwest. As the caption indicates, it was taken from a balloon flying above Folsom St., between 5th and 6th Streets in the SOMA (South of Market) neighborhood. Faint red ink labels some buildings and streets, but even at a glance some structures are readily recognizable. To the left is the burned-out shell of City Hall, close to but not exactly at the location of the building that replaced it in Civic Center. Just before City Hall is the U.S. Courthouse and Post Office (now the James R. Browning U.S. Court of Appeals Building), which had only been completed the previous year and survived the fire with minimal damage.At right is the San Francisco Call Building near Union Square with its ornate roof, the city's tallest building, which was badly damaged but not destroyed in the fire. Other notable buildings that survived the fire can be spotted, including the San Francisco Mint (now the 'Old San Francisco Mint') in the foreground at center and the Fairmount Hotel on Nob Hill in the background towards the right. Not far from the Mint at center-right is the triangular Phelan Building, which resembles the taller Flatiron Building in New York; it did not collapse but was so badly damaged that it was demolished and rebuilt. Just before the Phelan Building is the shell of the Emporium Department Store. In the foreground towards left, to the left of the Mint, is the California Casket Company Building - so recently built that it had not yet been occupied - which in a grim twist of irony survived the fire.

The sharpness of the image is such that figures on the ground can easily be made out. We can see that streetcar service had been restored and trains were running. Many horse-pulled carts ply the streets, engaged in the long process of removing rubble. Small groups of two or three individuals standing together are likely soldiers, as the Army was effectively running the city, including preventing looting, and managing relief efforts until July.

A handwritten annotation marks the 19th anniversary of the fire in 1925, presumably added by the photograph's original owner.

Taking the Photograph

This photograph was taken by George R. Lawrence on May 5, 1906, when significant cleanup and reconstruction work was just beginning. In order to capture the image, Lawrence employed a variety of novel methods, including stabilizing the camera by attaching it to long bamboo poles that were weighted over the sides of the balloon basket to prevent any movement from the wind (traingular 'smuges' at the left and right edge near center are in fact stabilizing booms attached to the basket holding the camera). He also created a special modified shutter to expose the more distant parts of the city at top for much longer than the area in the foreground, achieving a consistently high level of clarity throughout.This was one of a series of four large panoramic photographs taken by Lawrence from various points in the city in the weeks after the fire, all titled 'Ruins of San Francisco' and all scarce now.

San Francisco and the 1906 Earthquake

The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake struck on the morning of April 18. Although the earthquake itself caused considerable destruction, far worse were the fires that soon broke out in the city and raged for several days, being fed by the gas lines used for heating and lighting throughout the city. Similarly, critical pipes in the city's water supply were ruptured, leaving firefighters with a paltry supply to quell the infernos (by contrast, much of the Mission District was spared thanks to a single well-fed fire hydrant, afterwards known as 'the Golden Hydrant'). Some fires were inadvertently started by firefighters themselves, who dynamited buildings to create firebreaks, or intentionally by building owners whose insurance would cover fire damage but not damage from earthquakes.In the end, over eighty percent of the city (nearly 25,000 buildings and 490 city blocks) was destroyed. Some 3,000 people lost their lives and more than 200,000 - a majority of the city's population - were left homeless. It remains the deadliest event in California's history and ranks among the worst natural disasters in American history. Nevertheless, the determined and coordinated effort of the city's residents led to San Francisco's reconstruction in a handful of years, celebrated in grand style with the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition.

The catastrophe left a deep imprint on the city and the entire Bay Area. San Francisco's infrastructure, including its water supply, was completely reimagined and the city's rudimentary system of cisterns was expanded to provide an emergency water supply in case of a similar emergency. Neighborhoods along the edge of the most populated part of the city that survived the earthquake and fire (Pacific Heights, Noe Valley, Bernal Heights), quickly built housing for the suddenly-homeless refugees, though many lived for months in tents and military-style shacks or barracks (mostly built by the U.S. Army itself, stationed in the Presidio). Similarly, San Francisco's suburbs, especially in the East Bay, saw massive population increases in the months after the conflagration. New building codes were imposed and subsequently strengthened, leaving the city's buildings with onerous but effective requirements that helped prevent similar damage in later earthquakes (namely the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake).

Publication History and Census

This photograph was taken by George R. Lawrence, a Chicago-based photographer, on May 5, 1906, with a prominent note added at a later date at top. It is quite rare, only being cataloged among the holdings of the Library of Congress and the University of California Berkeley.Cartographer

George Raymond Lawrence (February 24, 1868 – December 15, 1938) was an American photographer renowned for his innovative contributions to large-format and aerial photography. Born in Ottawa, Illinois, he moved to Chicago around 1890 and began working at a buggy company, where he showed an adeptness for tinkering and technical innovations. In 1891, he opened a photography studio (Geo. R. Lawrence Company), where he experimented with new techniques with the rapidly evolving technology, including perfecting flashlight photography, which would become standard for years afterwards. He adopted the slogan: 'The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty.' In 1900, Lawrence constructed the world's largest camera to capture a single image of the Chicago & Alton Railway’s Alton Limited train. The camera weighed 1,400 pounds and utilized a glass plate measuring 8 feet by 4.5 feet. The resulting photograph earned the 'Grand Prize of the World' at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Lawrence also pioneered aerial photography, initially using manned balloons to capture elevated views. After experiencing a near-fatal accident when a balloon malfunctioned, he transitioned to using unmanned kites to lift cameras. This technique led to his iconic 1906 series of photographs, 'San Francisco in Ruins,' taken shortly after the devastating earthquake from hundreds of feet above the city. In addition to photographs taken at ground level showing the destruction, these panoramic photographs were a financial and reputational boon for Lawrence. However, later efforts, particularly a fruitless 1909 expedition to photograph animals in British East Africa, did not see similar successes. Facing something of a professional and personal crisis around 1910 (Lawrence's first wife discovered an affair and the two were divorced), he ventured into aviation design, securing numerous patents for aviation-related devices, though his aircraft company failed in 1919. Lawrence passed away in 1938 at the age of 70. More by this mapmaker...