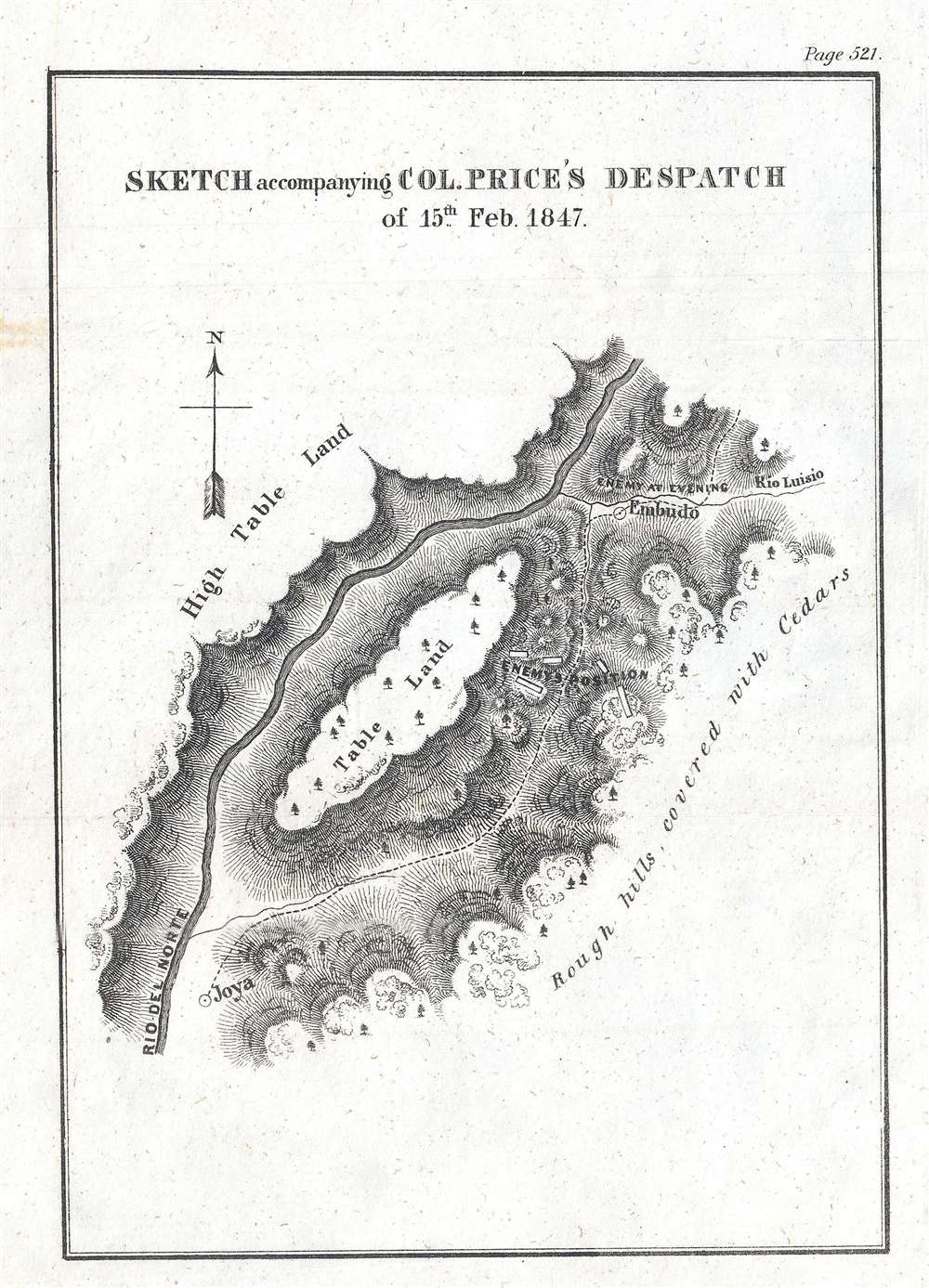

1847 Emory Map of Battle of Embudo Pass, New Mexico during the Taos Revolt

SketchFeb15-usgovt-1847

Title

1847 (undated) 8.75 x 6.5 in (22.225 x 16.51 cm)

Description

The Battle of Embudo Pass

The battle of Embudo Pass too place on January 29, as Colonel Price and his men marched toward Taos. The road cut through a canyon between the settlements of La Joya and El Embudo, where insurgents hoped to ambush the American soldiers. Price, however, learned of the insurgent's presence before he and his men arrived in the canyon. Price sent an officer and some of his men ahead to scout the terrain, and soon their enemies were discovered and quickly retreated so quickly through the difficult terrain that they defied pursuit by the attacking Americans. Price's force soon regrouped and entered Embudo without a fight.The Taos Revolt

The Taos Revolt was a January 1847 popular insurrection by Puebloan and Hispano allies against the U.S. occupation of New Mexico during the Mexican-American War. In every battle between the United States Army and militia and the Hispano and Puebloan rebels, the U.S. forces crushed the rebellion and the rebels soon abandoned open warfare. The rebellion began fermenting in August 1846, when U.S. forces under the command of Stephen Watts Kearny invaded New Mexico and captured Santa Fe without firing a shot. Kearny left for California, and left Colonel Sterling Price in command, who, in turn, appointed Charles Bent as New Mexico's first territorial governor. Many New Mexicans did not believe Governor Manuel Armijo made the right decision in surrendering to U.S. forces without a fight. They also resented how U.S. soldiers treated them, as they chose to act like conquerors. New Mexicans also feared that their land titles would not be recognized by the United States.Thus, when violence ignited on the morning of January 19, 1847, plenty of animosity was felt by the insurrectionists and their supporters. The revolt began in Don Fernando de Taos (present-day Taos, New Mexico) and was led by Pablo Montoya, a Hispano, and Tomás Romero, a Taos Puebloan. A Native American force, led by Romero, broke into Governor Bent's house and shot him with arrows and scalped him in front of his family. Bent survived the attack, and he and his family dug through the walls of their house into the house next door. When the insurrectionists discovered this, they killed Bent, but spared his wife and children. The following day, a force of approximately 500 Hispanos and Puebloans attacked Simeon Turley's mill in Arroyo Hondo, which was located a few miles outside Taos. An employee at the mill saw them coming and immediately left for Santa Fe to seek help from the occupying U.S. forces. Of the ten men left to defend the mill, only two survived by escaping under the cover of darkness on foot. That same day, seven or eight American traders were killed on their way to Missouri.

Colonel Price and the U.S. forces moved quickly to crush the revolt. He led a force of 300 U.S. troops, which was accompanied by sixty-five volunteers, some of which were New Mexican. Along the way to Taos, Price and his forces hammered a force of 1,500 Hispanos and Puebloans, before successfully recapturing Taos and the Taos Pueblo. A 'drumhead court-martial' was convened by Price once he had secured Taos, and, ultimately, fifteen men were found guilty of murder and treason and sentenced to death. By the end of the process, the U.S. hanged twenty-eight men in Taos in response to the revolt. A year later, the United States Secretary of War reviewed the process and stated that the map convicted of treason may have been wrongly convicted, an opinion upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. All the other convictions, however, were affirmed.

Publication History and Census

This map was created by William Hemsley Emory and published in a U.S. government report in 1847. While fairly well represented in institutional collections, this map is scarcely on the market.Cartographer

William Hemsley Emory (September 7, 1811 - December 1, 1887) was an American surveyor, civil engineer, and Army officer. Born in Queen Anne's County, Maryland, Emory graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1831, was assigned to the Fourth Artillery, and resigned from service in 1836 to pursue civil engineering. He returned to the army in 1838 to serve in the newly-formed Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. During the Mexican-American War, Emory served in the Army of the West under the command command of Stephen Watts Kearny. While serving with Kearny, he kept a detailed journal that was then published as Notes of a Military Reconnaissance from Fort Leavenworth to San Diego and soon became an important guidebook for the route to Southern California. After the war, Emory served as part of the team that surveyed the United States-Mexican border. When the American Civil War started, Emory was stationed in Indian Territory and immediately realized the likelihood that Confederates would capture him and his men. To avoid this, Emory quickly secured the services of Black Beaver, the famous Lenape warrior, to guide them out of the territory. Emory and his troops, on their way from Fort Washita to Fort Leavenworth, captured a number of their Confederate pursuers, which were the first prisoners taken during the war. Emory then served in the Army of the Potomac, in the Western Theater, and in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1854. After the war, Emory held the post of commander of the Department of the Gulf during Reconstruction and, in September 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered Emory to New Orleans, where he successfully negotiated a peace with the white supremacist paramilitary organization the White League, which led to the White League being disbanded. Emory married Matilda Wilkins Bache on May 29, 1838 in Philadelphia, with whom he had two sons, both of which served in the United States armed forces. Matilda Bache was Alexander D. Bache's sister. Alexander Bache was one of the most influential superintendents of the United States Coast Survey. More by this mapmaker...