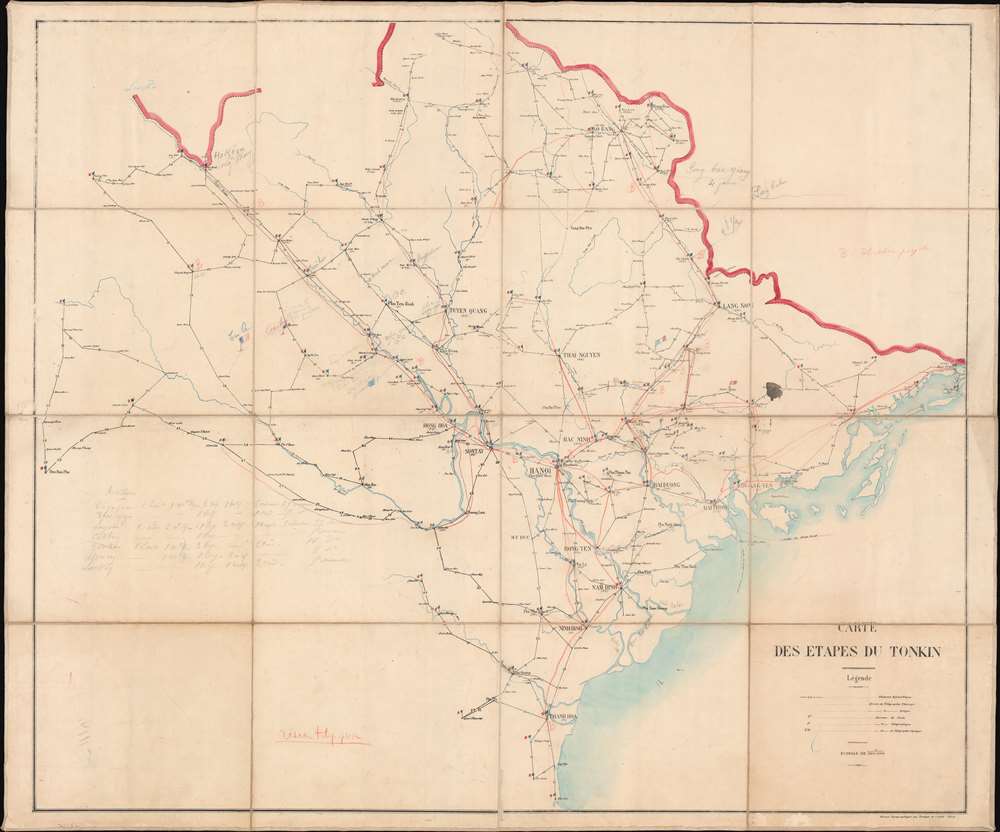

1889 French Bureau Topographique Map of Tonkin, Vietnam, Indochina

Tonkin-topographique-1894

Title

1894 (undated) 34.5 x 40.75 in (87.63 x 103.505 cm) 1 : 500000

Description

A Closer Look

This map depicts the Tonkin region, or northern Vietnam, which had been a French Protectorate (in reality, a colony) since France seized the area in the mid-1880s. The copious annotations suggest that the map was used by military officials during France's campaign of suppression against the Vietnamese in the early-mid 1890s. 'Etapes' in the title here is a little ambiguous, but most likely is a military term meaning storehouses of supplies for troops in the field or, by extension, the distance that an army can march in a day before stopping overnight at such a storehouse.Printed on the map are settlements, rivers, roads, and the border with China (still not fully demarcated, as is clear at top-left). Black lines between settlements are roads, with numbers noting the distance in kilometers. The letters P., T., and O. in parentheses are explained in the legend as offices for post and telegraphy. Aside from French flags (perhaps indicating a garrison), hand-drawn annotations include the names of towns and waterways. Red lines and circles illustrate the networks of telegraph lines and optical telegraph stations. A red and black flag in Bien Dong at right-center instead of the French Tricolore suggests that French forces did not control the area. A list at left-center appears to note the movements of troops between different villages with the dates noted.

Near Lao Kay (Lào Cai) at the top-left is a hand-written note indicating 'Ho Kéou,' that is, Hekou (河口) in Yunnan Province, China. Already an important border crossing and trade entrepôt when this map was made, it would become the point at which the Kunming-Haiphong Railway, built in the first decade of the 20th century, would cross from Vietnamese to Chinese territory. The French would eventually establish customs houses and consulates at towns along the railway's route and at other Chinese towns along the border, effectively extending their colonial presence in Tonkin into China.

French Forays into Tonkin

French interest in Vietnam began in the 17th century with Catholic missionaries who tended to become entangled in political matters and were often executed as a result. This 'persecution' of Catholics provided France a convenient excuse to launch repeated military expeditions against the Nguyễn Dynasty, which, ironically, the French helped establish in the late 18th century. Beginning with Cochinchine in 1862, French interests in Vietnam expanded continuously, with the aim of reaching southern China (Yunnan and Guangxi) and establishing a French sphere of influence there. At this time, French commercial interests in China were falling far behind the British, but an exclusive sphere over Yunnan via Vietnam could balance against British influence and allow France to profit from opium production. In the 1860s, French protectorates were also established over Cambodia and Laos to protect Vietnam from British and/or Siamese interference.Aside from kingmaking missionaries, French military officers in Vietnam had a habit of 'going rogue' and attempting to seize major Vietnamese cities. In 1873, a French trader, gun runner, and mercenary named Jean Dupuis was becoming a major problem in Franco-Vietnamese relations in Hanoi. But when the French sent a military detachment to expel Dupuis, the expedition's leader, François Garnier, instead sided with Dupuis and stormed the citadel of Hanoi. Though heavily outnumbered, the French forces had the benefit of surprise and captured the city before moving on to conquer much of the Red River Delta. However, this action prompted an intervention by highly-effective Chinese-Vietnamese irregular forces led by Liu Yongfu (劉永福), known as the 'Black Flag Army' (pavillons or drapeaux noirs, 黑旗軍). As the French government and military command had never approved Garnier's operations and were not interested in a wider war with China, a treaty was negotiated returning Hanoi and other cities to the Nguyễn in exchange for a range of concessions to the French, including expanded trading rights in Tonkin.

The Tonkin Campaign and the Sino-French War

Nine years later, in 1882, another French officer named Henri Rivière followed in Garnier's footsteps and, after being sent to investigate misdeeds by French traders in Hanoi, took it upon himself to likewise seize the citadel in Hanoi without orders. Again, the Vietnamese called in the Black Flag Army and requested assistance from formal Chinese forces, the Yunnan and Guangxi Armies. A negotiated settlement between France and China seemed to avert a wider war, but Rivière attacked Nam Định, hoping to provoke a more thoroughgoing French intervention. In the interim, an election in France had returned the pro-colonial Jules Ferry to power as Prime Minister. When the Black Flag Army dealt a serious defeat to the French outside of Hanoi at the Battle of Paper Bridge in May 1883, killing Rivière in the process, the Ferry government determined to launch a full-scale military expedition, initiating a campaign that would drag on for three years and expand into a war with China.The French force (largely composed of Cochinchinese tirailleurs and local 'Yellow Flag' forces), intending to exact revenge on the Chinese and the Black Flag Army, had as a final objective the occupation of Tonkin and the establishment of a protectorate. The fighting in Tonkin raged from June 1883 until July 1884, before the Chinese entered the war in earnest and the wider Sino-French War (1884 - 1885) began. The Sino-French War lasted from August 1884 until April 1885, with the French seeing major victories early on but encountering stiff resistance as they approached the upper reaches of the Red River and the Chinese border. Eventually, a string of Chinese/Black Flag victories, including at Zhennan Pass (鎮南關) near Đồng Đăng (towards top-right), forced France to retreat from Lạng Sơn in March 1885, an embarrassing setback that brought down Ferry's government. Afterward, France and China signed a treaty recognizing a French protectorate over Tonkin. But remnants of the Black Flags combined with indigenous resistance fighters (the Cần Vương) to harass French forces (and Vietnamese Christians) in Tonkin, seizing large portions of the region. The French began a year-long pacification campaign, and by April 1886, fighting mostly ended.

'Pacifying' Tonkin

Nonetheless, Tonkin was not effectively pacified until about 1896, a decade later. Presaging the difficulties that France and later the United States would face in maintaining control over Vietnam in the 20th century, insurgents used hit-and-run tactics, dispersing before a force could be assembled to retaliate. French outposts were vulnerable to attack, and their supply lines were far from assured. Still, in the late 1880s and early 1890s, the French gradually extended their control over Tonkin, also dislodging a Siamese force that had occupied Dien Bien Phu (at left) in the process. The appointment of Jean Marie Antoine de Lanessan as Governor-General of Indochine in 1891, along with the fortuitous presence of several highly capable military commanders, allowed the French to combine military and political measures to isolate the insurgents and win over the rural population. The adoption of 'oilstain' tactics by the French, whereby territory was incrementally taken, secured, and fortified before further advances were made, proved highly effective. Still, remnant insurgents continued to operate, more as bandits than a revolutionary force, and the French continued to send troops on 'sweeps' through the Red River Delta while also resorting to building a string of blockhouses along the border with China to deter incursions from cross-border insurgents.Publication History and Census

This map was produced by the Bureau Topographique des Troupes de l'Indo-chine. The only other two known examples of the map are held by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which incorporate the annotations here as printed material. The first of the two BNF maps (digitized as OCLC 1177102370) is simpler, and the second (digitized as OCLC 1177103335) is more elaborate, suggesting that the present map is a proof state or first printing, followed by two states incorporating progressively more of the information included here. An 1899 map of the same title (digitized by BNF as OCLC 1177107263) also looks to be based on the present map, though with noticeable differences, as its focus is more administrative than military.Cartographer

Bureau Topographique des Troupes de l'Indo-chine (fl. c. 1886 - 1900) was founded in 1886 in Hanoi. Its first major project was a 1:2000000 map of the entirety of Indochina, for which they drew on source maps created by the Service Hydrographique de la Marine and those created by an expeditionary corps sent throughout the region. Before establishing its own printing facilities in Indochina in 1890, the Bureau Topographique transferred their work back to Paris to be printed by the Service Géographique de l'Armée. In 1890 the Bureau Topographique also began to increase its cartographic output. The Bureau Topographique sent army officers on triangulation and topographic missions in unexplored areas of Indochina throughout the 1890s, some of which proved fatal for the participants. It is unclear when the Bureau Topographique shut down, but no examples of their work postdate 1900. More by this mapmaker...