This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

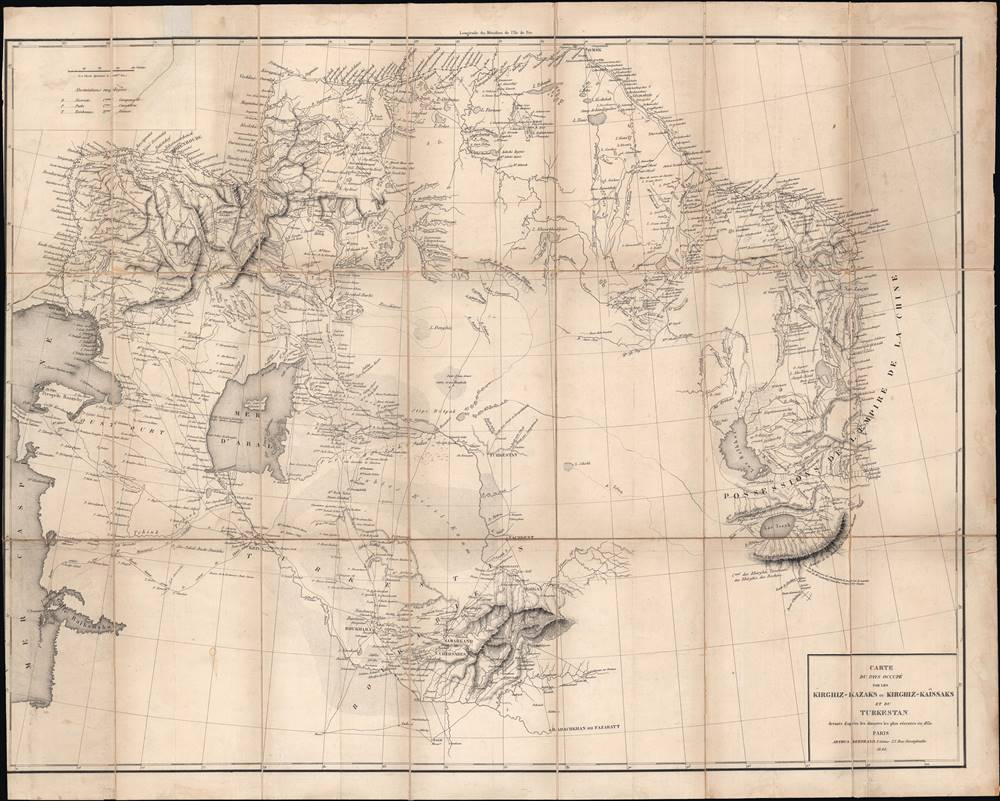

1840 Arthus-Bertrand / Levshin Map of Central Asia; Russian Empire

Turkestan-arthusbertrand-1840

Title

1840 (dated) 20.5 x 26.5 in (52.07 x 67.31 cm) 1 : 4500000

Description

A Closer Look

This map stretches from the Russian frontier, including a string of forts known at the time as the Orenburg Line, at top to the oasis cities of Samarkand and Bukhara in the south, and from the Caspian Sea in the west to the edge of the Qing Empire in the east. The map becomes less detailed as it moves away from the Russian frontier, due to both a lack of knowledge and the sparseness of population in the steppes and deserts between cities. Distances are shown in Russian verstes, as in the original. Prominent at center-left is the Aral Sea, famous in recent decades for environmental disaster; much of the lake has now dried up.Aside from its contemporary relevance for Russia's conquest of Central Asia, this map is also an important reminder that the borders and ethnic divisions of Central Asia are a recent creation, externally imposed by the Russian and Soviet empires, rather than natural endogenous divisions endogenous.

Russia's Conquest of Central Asia

Russian contacts with Central Asia predated this map by centuries and Russian national identity is largely rooted in the relationship with the steppe and interaction (trade, warfare, etc.) with steppe-dwelling peoples, including the Mongols. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Russian Empire established a series of border forts that roughly followed the edge of the forested land before reaching the steppe, also concurrent with the present-day border between the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan. Occasional forays into the steppes were attempted but conquering those territories in any meaningful sense remained elusive. Orenburg (Orenbourg here), at top-left, was particularly important for gaining information on and preparing military campaigns against the steppe-dwelling peoples to the south and east.Using the latest military, communication, and transportation technology, the Russian Empire focused intently in the mid-19th century on subjugating Central Asia. Although the region had lost some of its wealth and luster from the height of the Silk Road, it was still home to powerful states that held their own in tussles with neighboring empires in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

The Russians also encountered difficulties in trying to control the region, starting with a disastrous attack on Khiva in 1839. Rather than military strategy or technology, the main obstacle for the Russians was supplying troops so far from the heartland in a region with minimal infrastructure. Getting supplies to Orenburg was difficult enough, but then they needed to be moved across vast distances through desert and steppe. What could not be moved up rivers had to be carried over land, usually by caravans of horses, oxen, and camels, which required their own food and water. Thus, Russian progress into Central Asia was consistent but slow, and was aided by tensions between the independent states. It was only in the final stage of the Russian conquest of Central Asia that railways reached the region, greatly aiding the control of Central Asia after conquest and facilitating the arrival of colonists.

Although there had been some in-depth studies of the region by Russian Orientalist scholars, including Levshin, at the time this map was made, understanding of Central Asia, its geography, and the peoples who lived there remained hazy. This was in part a result of an attempt to inscribe taxonomic distinctions on a complex reality, replacing religious identities with ethnic identities in the process, and in part the repurposing of old terms for new purposes. Also, the common origin and multiple meanings of the term Cossack and Kazakh (qazaq) shared in different Turkic languages and borrowed in Russian was particularly confusing. Thus, the differences between 'Tatars,' 'Turks,' 'Kazakhs,' 'Kirghiz,' and other groups were very uncertain.

'The Great Game'

Though made for a French-speaking audience, this map was made in the context of the early phase of the 'Great Game,' which was a diplomatic confrontation between the British and Russian Empires over territories in Central and Southern Asia. The conflict revolved around Afghanistan, which, while lacking significant resources of its own, was strategically situated. Russia feared Britain was making commercial and military inroads into Central Asia, an area long within the sphere of influence of St. Petersburg. Britain, conversely, feared Russia making gains in India, 'the jewel in the crown' of British Asia. The escalating tensions led to several wars and proxy wars in India and Afghanistan, were connected with the Russian annexations of Khiva, Bukhara, and Kokand, and tied to wider geopolitical tensions between Russia and Britain, evident in the Crimean War and elsewhere.Franco-Russian Relations in the Long 19th Century

Russia had played a critical role in the defeat of Napoleon and the immediate post-Napoleonic order in Europe, debated at the Congress of Vienna, was meant to satisfy Russian demands for territorial expansion without allowing the empire to become a hegemonic force in Europe. Therefore, thanks in part to the slick negotiating of Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (known simply as Talleyrand), other European powers were reluctantly lenient towards France, hoping it would re-emerge as a somewhat powerful force and act as a counter-balance to Russia. However, for most of the next century and into World War I France and Russia enjoyed good relations due to a shared antagonism towards Great Britain and Prussia/Germany. An exception was a period of bad relations under Louis-Napoleon when France fought against Russia in the Crimean War (1853 - 1856).Publication History and Census

This map, originally produced in 1831 and titled ' Map of the Lands belonging to the Kirghiz-Kazakhs and Turkestan' (Карта Земель, принадлежащих Киргиз-Казакам и Туркестана), accompanied Levshin's 1832 book Description of the Kirghiz-Cossack, or Kirghiz-Kaissak, hordes and steppes (Описаниие Киргиз-Казачьих, или, Киргиз-Кайсацкских орд и степей). Levshin's book was translated into French by Ferry de Pigny (c. 1790 – 1880), a renowned Russian-French translator, and published in 1840. Therefore, it is possible that this map was meant to accompany Ferry de Pigny's translation. On the other hand, the fact that this is a folding map and was produced by Claude Arthus-Bertrand, a former military officer in the employ of the French navy, suggests that it had a military use and was published separately from Ferry de Pigny's translation. This map is only known to be held by the Spanish Ministry of Defense Library and is very scarce to the market.CartographerS

Claude Arthus-Bertrand (1769-1840) was a French army officer during the French Revolution. In the Napoleonic era, he founded a firm (Arthus-Bertrand, 1803 – present) that specializes in producing military medals, decorations, and insignia, often for the French government. Arthus-Bertrand was also an enthusiast of scientific expeditions and founded a publisher to promote them, which became the official editor of the Ministère de la Marine in the 1830s, where it oversaw the publication of the accounts of the 1836 – 1837 Bonite expedition that circumnavigated the globe. More by this mapmaker...

Aleksei Iraklievich Levshin (Алексей Ираклиевич Левшин; 1798 - 1879) was a Russian statesman, historian, writer, and ethnographer. Born to a wealthy family, he studied at the Kharkiv Imperial University and the Collegium of Foreign Affairs, after which he was posted to the Orenburg Border Commission and undertook an intensive study of nearby Central Asian populations in Russia and what is now Kazakhstan, making him a pioneer in the study of Central Asia in Europe. He later took on several government duties and advocated for the emancipation of the serfs. He was also a founding member of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. Learn More...