1984 Lopatto Polish Historical Map of Warsaw, World War II

WarsawWWII-lopatto-1984$1,200.00

Title

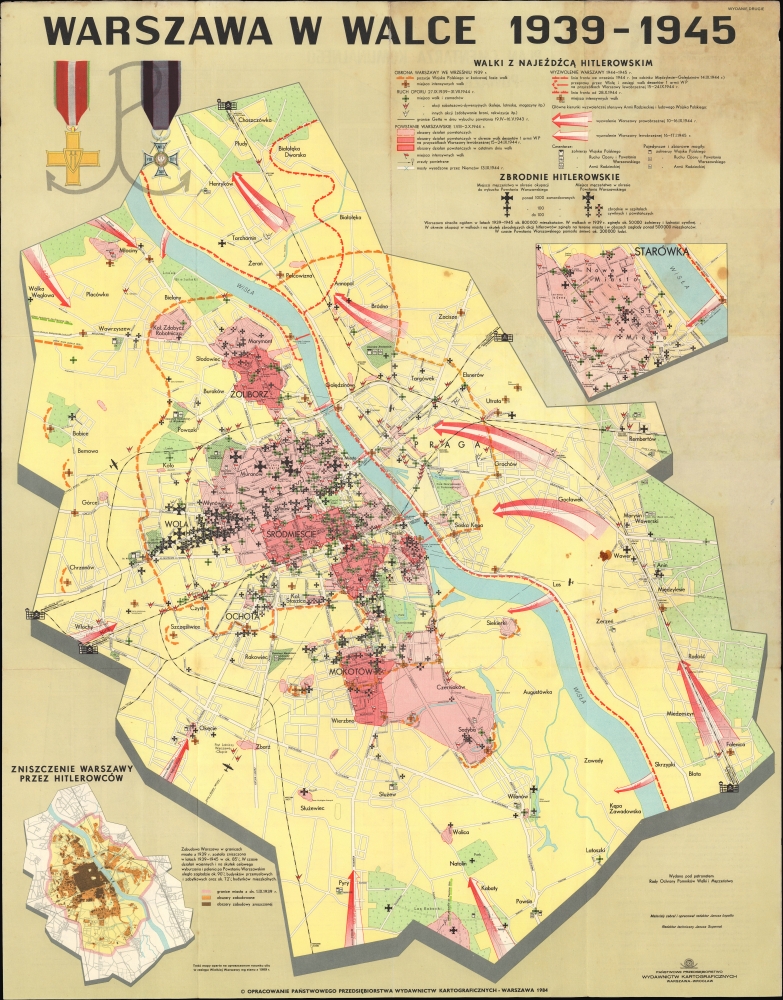

Warszawa w walce 1939-1945.

1984 (dated) 29.25 x 22.75 in (74.295 x 57.785 cm) 1 : 42000

1984 (dated) 29.25 x 22.75 in (74.295 x 57.785 cm) 1 : 42000

Description

This is a 1984 Państwowe Przedsiębiorstwo Wydawnictw Kartograficznych map of Warsaw, highlighting the city's traumatic experience during the Second World War. Warsaw was one of the most heavily damaged large cities in the entire conflict, losing some 85 percent of its prewar structures by 1945 and several hundred thousand of its inhabitants, including almost the entirety of its prewar Jewish population.

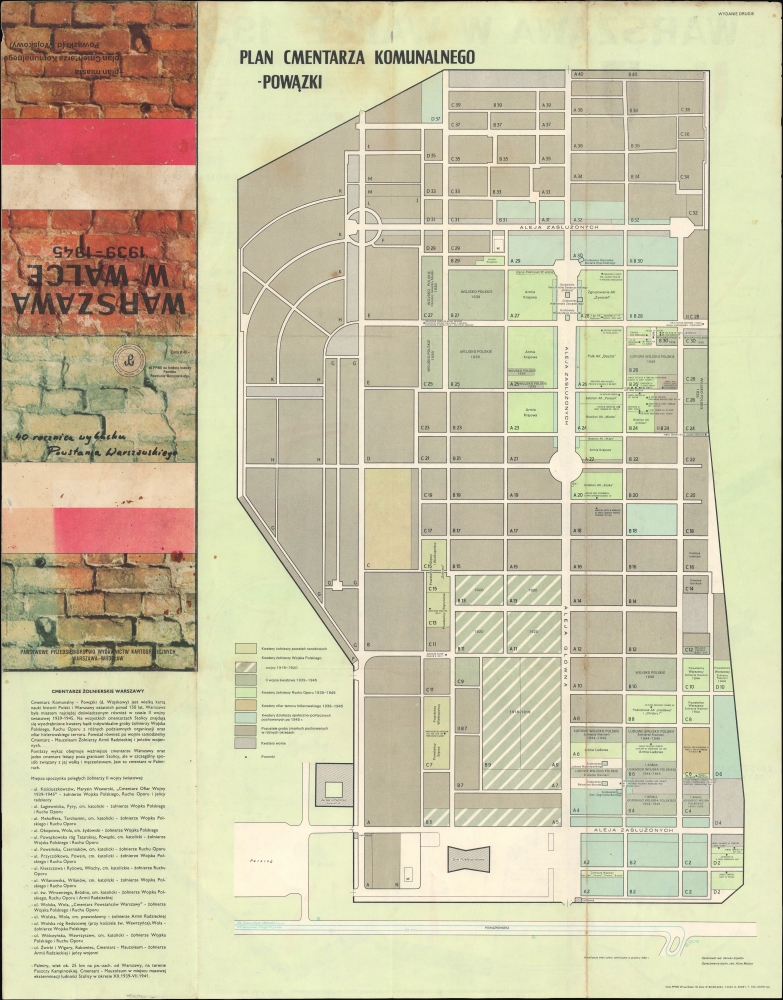

An inset just below the legend highlights the Old City (Starówka) of Warsaw, which was almost completely destroyed during the war. The inset at the bottom-left displays the city's 1939 borders, with the built-up areas shaded orange and areas destroyed during the fighting (some 85 percent of the developed areas) shaded brown. The verso consists mainly of a plan of the Powązki Cemetery, the city's best-known necropolis, containing, as indicated, dead from the various stages and fronts of Poland's battle against the Germans.

Roughly a year after capturing Warsaw, the Germans began to concentrate the city's Jewish population (nearly 400,000 before the war, increased to roughly 500,000 by refugees from elsewhere in Poland) into a 1.3 square mile area that became the Warsaw Ghetto. Packed in extremely cramped conditions with little food, medicine, or other essentials, the residents of the ghetto suffered tremendously, and many thousands died from execution, disease, starvation, exposure to the elements, and other causes. However, most would die in the summer of 1942 in Grossaktion Warschau, the implementation of the 'Final Solution' in the city, which saw 265,000 Polish Jews sent in groups to the Treblinka extermination camp fifty miles northeast of Warsaw and killed soon after arrival. By the time the last groups of Jews were being assembled to be sent to Treblinka, news of the extermination camps had reached Warsaw, and the ghetto's inhabitants decided to die fighting rather than in a gas chamber. With virtually no weapons at their disposal aside from what they captured, several hundred Jewish partisans managed to fight on for nearly a month (April 19 - May 16, 1944) before being fully suppressed or escaping with the help of Polish underground fighters. In the aftermath of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the ghetto was completely leveled by the Germans.

A similar fate would befall the rest of the city the following year when the Germans employed equally brutal tactics during the Warsaw Uprising (August 1 - October 2, 1944). By July 1944, the Soviet Red Army was steadily advancing into Poland and heading towards Warsaw. The Polish government-in-exile in London, which had cooperated to an extent with Stalin during the war but was generally deeply distrustful of him, approved plans for an uprising by the underground Home Army to reclaim the capital before the Soviets could capture it and assert Polish sovereignty. As a result, Stalin's troops stopped at the east bank of the Vistula in September 1944 and watched the ongoing battle between Polish partisans and the Germans, hoping they would exhaust each other and make the subsequent conquest of the city easier. Unsurprisingly, no mention of such machinations is made here, though considerable attention is paid to an attempted attack across the Vistula by the First Polish Army, a Polish unit within the Red Army, which briefly established bridgeheads and evacuated some refugees before being driven back at high cost. However, this operation was likely undertaken by the unit's commander, Gen. Zygmunt Berling (1896-1980), without the authorization of his Soviet superiors (he was reassigned afterward), and in any event, was not reinforced by the immense Soviet arsenal amassed on the eastern side of the river.

By the time the Warsaw Uprising ended (through an agreement between the Germans and Poles), thousands of German and partisan troops had died, along with hundreds of thousands (perhaps 200,000) civilians. Much of the city was heavily damaged in the fighting, and after the remaining civilians had been expelled, the Germans set about systematically destroying it, intending to erase it from the face of the earth. When the Soviets launched the Vistula-Oder Offensive on January 12, 1945, capturing Warsaw was a quick and easy operation, completed in less than a week. Nearly the entire city was destroyed and, although gradually rebuilt after the war, many historical buildings, documents, and artifacts central to Polish national identity were lost forever.

A Closer Look

The map presents Warsaw and its environs with a wide range of information covering the entire span of the war. Orange symbols and crosses refer to the defense of the city in September 1939, when it was besieged and heavily bombarded by German troops. Acts of resistance during the German occupation are denoted with green crosses, and civilian 'martyrs' are identified with black crosses. The Jewish Ghetto, the site of a significant uprising in the spring of 1943, is outlined in black. The area of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising is shaded red, with the black crosses for civilian deaths including the date ('44) for distinction. Additional symbols indicate Soviet offensives and the location of military cemeteries (also listed on the verso) and civilian mass graves.An inset just below the legend highlights the Old City (Starówka) of Warsaw, which was almost completely destroyed during the war. The inset at the bottom-left displays the city's 1939 borders, with the built-up areas shaded orange and areas destroyed during the fighting (some 85 percent of the developed areas) shaded brown. The verso consists mainly of a plan of the Powązki Cemetery, the city's best-known necropolis, containing, as indicated, dead from the various stages and fronts of Poland's battle against the Germans.

Occupations and Uprisings

Warsaw faced bombardment from the opening hours of Germany's invasion on September 1, 1939, sustaining Luftwaffe raids nearly continuously. Within a week, the Germans were advancing on the city and captured it on October 1. Already, some 10 percent of the city was destroyed, including the Royal Palace. Polish politicians, intellectuals, and other potential resistance leaders in Warsaw were arrested and executed en masse, while many others were sent to concentration camps to work as forced laborers.Roughly a year after capturing Warsaw, the Germans began to concentrate the city's Jewish population (nearly 400,000 before the war, increased to roughly 500,000 by refugees from elsewhere in Poland) into a 1.3 square mile area that became the Warsaw Ghetto. Packed in extremely cramped conditions with little food, medicine, or other essentials, the residents of the ghetto suffered tremendously, and many thousands died from execution, disease, starvation, exposure to the elements, and other causes. However, most would die in the summer of 1942 in Grossaktion Warschau, the implementation of the 'Final Solution' in the city, which saw 265,000 Polish Jews sent in groups to the Treblinka extermination camp fifty miles northeast of Warsaw and killed soon after arrival. By the time the last groups of Jews were being assembled to be sent to Treblinka, news of the extermination camps had reached Warsaw, and the ghetto's inhabitants decided to die fighting rather than in a gas chamber. With virtually no weapons at their disposal aside from what they captured, several hundred Jewish partisans managed to fight on for nearly a month (April 19 - May 16, 1944) before being fully suppressed or escaping with the help of Polish underground fighters. In the aftermath of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the ghetto was completely leveled by the Germans.

A similar fate would befall the rest of the city the following year when the Germans employed equally brutal tactics during the Warsaw Uprising (August 1 - October 2, 1944). By July 1944, the Soviet Red Army was steadily advancing into Poland and heading towards Warsaw. The Polish government-in-exile in London, which had cooperated to an extent with Stalin during the war but was generally deeply distrustful of him, approved plans for an uprising by the underground Home Army to reclaim the capital before the Soviets could capture it and assert Polish sovereignty. As a result, Stalin's troops stopped at the east bank of the Vistula in September 1944 and watched the ongoing battle between Polish partisans and the Germans, hoping they would exhaust each other and make the subsequent conquest of the city easier. Unsurprisingly, no mention of such machinations is made here, though considerable attention is paid to an attempted attack across the Vistula by the First Polish Army, a Polish unit within the Red Army, which briefly established bridgeheads and evacuated some refugees before being driven back at high cost. However, this operation was likely undertaken by the unit's commander, Gen. Zygmunt Berling (1896-1980), without the authorization of his Soviet superiors (he was reassigned afterward), and in any event, was not reinforced by the immense Soviet arsenal amassed on the eastern side of the river.

By the time the Warsaw Uprising ended (through an agreement between the Germans and Poles), thousands of German and partisan troops had died, along with hundreds of thousands (perhaps 200,000) civilians. Much of the city was heavily damaged in the fighting, and after the remaining civilians had been expelled, the Germans set about systematically destroying it, intending to erase it from the face of the earth. When the Soviets launched the Vistula-Oder Offensive on January 12, 1945, capturing Warsaw was a quick and easy operation, completed in less than a week. Nearly the entire city was destroyed and, although gradually rebuilt after the war, many historical buildings, documents, and artifacts central to Polish national identity were lost forever.

Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by the Polish State Enterprise of Cartographic Publishing Houses (Państwowe Przedsiębiorstwo Wydawnictw Kartograficznych) in 1984. Janusz Łopatto served as editor and Janusz Supernat as technical editor. There are three editions of this map: the first, published in 1969; the second, published in 1970; and the present edition, which is the third. Perhaps two dozen institutions, mostly in Europe, hold the map in its various editions.Condition

Good. Light wear along original fold lines. Slight loss along central fold line in map title, else very good.

References

OCLC 13217161 et al.