This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

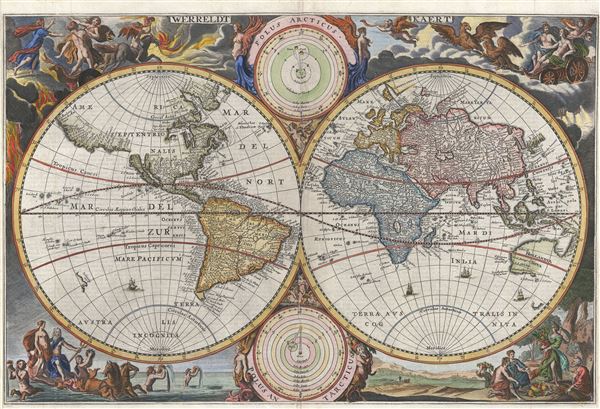

1682 Keur and Visscher Map of the World in Two Hemispheres

WerreldtKaert-keurvisscher-1682

Title

1682 (undated) 13 x 19 in (33.02 x 48.26 cm) 1 : 90000000

Description

Our survey of this map will begin in North America where Keur has updated Visscher's model to incorporate the convention of a flat topped insular California. The concept of an insular California first appeared as a work of fiction in Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo's c. 1510 romance Las Sergas de Esplandian, where he writes

Know, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.Baja California was subsequently discovered in 1533 by Fortun Ximenez, who had been sent to the area by Hernan Cortez. When Cortez himself traveled to Baja, he must have had Montalvo's novel in mind, for he immediately claimed the 'Island of California' for the Spanish King. By the late 16th and early 17th century ample evidence had been amassed, through explorations of the region by Francisco de Ulloa, Hernando de Alarcon, and others, that California was in fact a peninsula. However, by this time other factors were in play. Francis Drake had sailed north and claimed 'New Albion' near modern day Washington or Vancouver for England. The Spanish thus needed to promote Cortez's claim on the 'Island of California' to preempt English claims on the western coast of North America. The significant influence of the Spanish crown on European cartographers caused a major resurgence of the Insular California theory. Around the same time this map was drawn Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit missionary, published his own 1705 account of travels overland from Mexico to California, establishing conclusively the peninsularity of California. In one of the major deviations from the earlier 1658 Visscher map, here, after a small strait, the land of Nova Albion continues westward towards Asia until passing off the map, notably not to reappear on the opposite hemisphere.

The complete absence of the Great Lakes is of particular interest and is the most ephemeral element of this map, being updated in subsequent editions to reflect ongoing European exploration of the region.

Further south the cartography of South America is nearly as confused as that of North America. Though by this point in history, the general outlines of South America are well established by regular circumnavigations of the continent, the interior is entirely speculative. Even the great Amazon River is poorly and inaccurately rendered both regarding its general orientation and its connection with other large South American river systems, most notably the Paraguay. Visscher also recognizes two popular misconceptions regarding the mythical kingdoms of the Amazon, El Dorado and Xarayes.

In Visscher and Keur's times many Europeans believed that the most likely site of el Dorado was the mythical city of Manoa located here on the shores of the Lake Parima, near modern day Guyana, Venezuela, or northern Brazil. Manoa was first identified by Sr. Walter Raleigh in 1595. Raleigh does not visit the city of Manoa (which he believes is el Dorado) himself due to the onset of the rainy season, however he describes the city, based on indigenous accounts, as resting on a salt lake over 200 leagues wide. This lake, though no longer mapped as such, does have some basis in fact. Parts of the Amazon were at the time dominated by a large and powerful indigenous trading nation known as the Manoa. The Manoa traded the length and breadth of the Amazon. The onset of the rainy season inundated the great savannahs of the Rupununi, Takutu, and Rio Branco or Parima Rivers. This inundation briefly connected the Amazon and Orinoco river systems, opening an annual and well used trade route for the Manoans. The Manoans who traded with the Incans in the western Amazon, had access to gold mines on the western slopes of the Andes, and so, when Raleigh saw gold rich Indian traders arriving in Guyana, he made the natural assumption for a rapacious european in search of el Dorado. When he asked the Orinocans where the traders were from, they could only answer, 'Manoa.' Thus did Lake Parime or Parima and the city of Manoa begin to appear on maps in the early 17th century. The city of Manoa and Lake Parima would continue to be mapped in this area until about 1800.

Still, further south Visscher maps a large and prominent Laguna de Xarayes as the northern terminus of the Paraguay River. The Xarayes, a corruption of 'Xaraies' meaning 'Masters of the River,' were an indigenous people occupying what are today parts of Brazil's Matte Grosso and the Pantanal. When Spanish and Portuguese explorers first navigated the Paraguay River, as always in search of El Dorado, they encountered the vast Pantanal flood plain at the height of its annual inundation. Understandably misinterpreting the flood plain as a gigantic inland sea, they named it after the local inhabitants, the Xaraies. The Laguna de los Xarayes, accessible only through the Gate of Kings, almost immediately began to appear on early maps of the region and, at the same time, took on a legendary aspect. The Lac or Laguna Xarayes was often considered to be a gateway to the Amazon and the Kingdom of El Dorado. Here Visscher's rendering suggest exactly that, with a wide navigable Rio De La Plata leading directly to the Paraguay River and connecting clearly to the Lago de los Xarayes and thus the Amazon itself.

Crossing the Atlantic we find ourselves on the great continent of Africa. Like South America, Africa is well mapped along its shores but speculative in the interior. With regard to the course of the Nile, Visscher followed the Ptolemaic two-lakes-at-the-base-of-the-Montes-de-Lune theory. South of Ptolemy's lakes, in modern day South Africa, we encounter the Kingdom of Monomatapa. This region of Africa held a particular fascination for Europeans since the Portuguese first encountered it in the 16th century. At the time, this was a vast empire called Mutapa or Monomotapa that maintained an active trading network with faraway partners in India and Asia. As the Portuguese presence in the region increased in the 17th century, the Europeans began to note that Monomatapa was particularly rich in gold. They were also impressed with the numerous well-crafted stone structures, including the mysterious nearby ruins of Great Zimbabwe. This combination led many Europeans to believe that Ophir or King Solomon's Mines, a sort of African El Dorado, must be hidden in the area. Monomotapa did in fact have rich gold mines in the 15th and 16th centuries, but most have these had been exhausted by the 1700s.

Moving into Asia, Visscher offers us a fairly accurate mapping of Asia Minor, Persia and India. The Caspian Sea is erroneously oriented on east-west axis and is a bit lumpy in form. He names numerous Silk Route cities throughout Central Asia including Samarkand, Tashkirgit, Bukhara, and Kashgar.

Visscher maps, but does not name, the apocryphal Lake of Chiamay roughly in what is today Assam, India. Early cartographers postulated that such a lake must exist to source the four important Southeast Asian river systems: the Irrawaddy, the Dharla, the Chao Phraya, and the Brahmaputra. This lake began to appear in maps of Asia as early as the 16th century and persisted well into the mid-18th century. Its origins are unknown but may originate in a lost 16th century geography prepared by the Portuguese scholar Jao de Barros. It was also heavily discussed in the journals of Sven Hedin, who believed it to be associated with Indian legend that a sacred lake linked several of the holy subcontinent river systems. There are even records that the King of Siam led an invasionary force to take control of the lake in the 16th century. Nonetheless, the theory of Lake Chiamay was ultimately disproved and it disappeared from maps entirely by the 1760s.

The elaborate cartouche work surrounding the map proper is of special note. Dutch of the 17th century maps are ironically decorative due largely to their elaborate allegorical border work. Visscher's map is notable as establishing a border model that numerous cartographers, including Van Loon, Stoopendaal, Robyn, Bormeester, and others would follow. The border work, drawn by the Dutch artist Nicolaes Berchem, containings allegorical images drawn from classical mythology, including scenes representing the rape of Persephone, Poseidon and his followers, Zeus and his chariot, and Demeter receiving offerings.

This map appeared only in the 1682 edition of the Keur Bible. Subsequent editions replaced the present map with another, more common map, engraved (also after Visscher) by Daniel Stoopendaal.

Cartographer

Claes Jansz Visscher (1587 - 1652) established the Visscher family publishing firm, which were prominent Dutch map publishers for nearly a century. The Visscher cartographic story beings with Claes Jansz Visscher who established the firm in Amsterdam near the offices of Pieter van den Keer and Jadocus Hondius. Many hypothesize that Visscher may have been one of Hondius's pupils and, under examination, this seems logical. The first Visscher maps appear around 1620 and include numerous individual maps as well as an atlas compiled of maps by various cartographers including Visscher himself. Upon the death of Claes, the firm fell into the hands of his son Nicholas Visscher I (1618 - 1679), who in 1677 received a privilege to publish from the States of Holland and West Friesland. The firm would in turn be passed on to his son, Nicholas Visscher II (1649 - 1702). Visscher II applied for his own privilege, receiving it in 1682. Most of the maps bearing the Visscher imprint were produced by these two men. Many Visscher maps also bear the imprint Piscator (a Latinized version of Visscher) and often feature the image of an elderly fisherman - an allusion to the family name. Upon the death of Nicholas Visscher II, the business was carried on by the widowed Elizabeth Verseyl Visscher (16?? - 1726). After her death, the firm and all of its plates was liquidated to Peter Schenk. More by this mapmaker...