This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

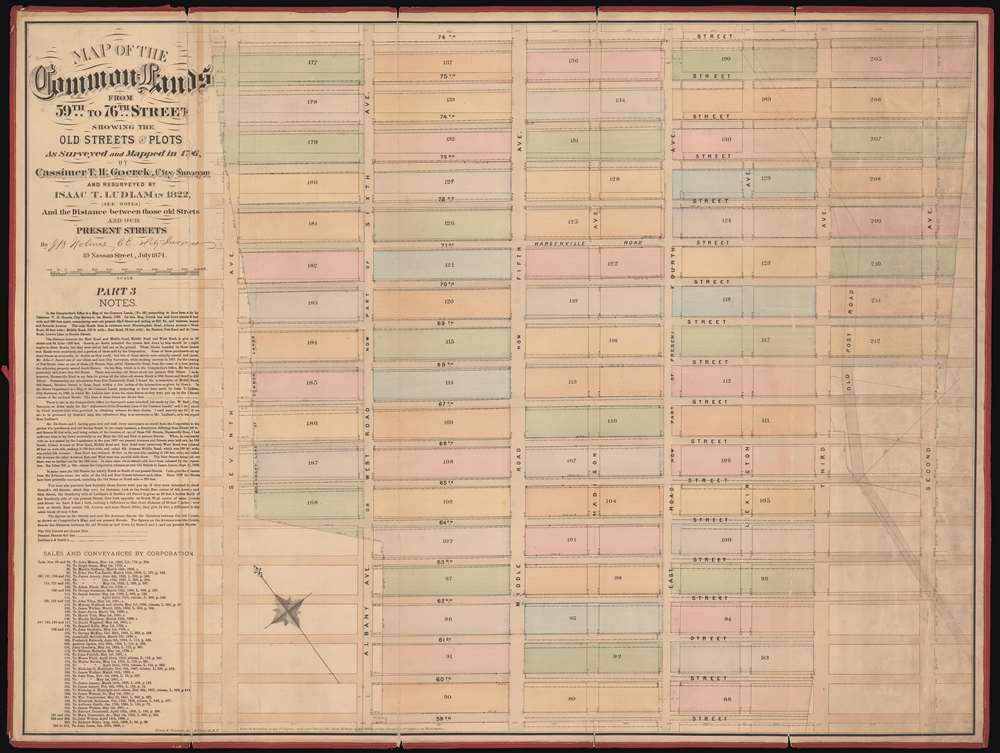

1874 Holmes Map of Lenox Hill, Manhattan, New York City

24-CommonLands59thto76th-holmes-1874

Title

1874 (dated) 24.5 x 32.625 in (62.23 x 82.8675 cm) 1 : 2400

Description

Common Lands

Settlement on Manhattan Island began at the southern tip, where Battery Park is today. One of the easiest indicators for modern-day visitors is the lack of an organized street-grid in this part of the city. Growth farther north on Manhattan Island was slow, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries. Then, even when people decided they wanted to live outside of the organized settlement, they elected to purchase land along either the Hudson River or the East River so they could easily travel into the city either by boat along the river or one of the two main roads that traveled north up the island. These roads, the Bloomindale Road (now Broadway), which led up the west side of the island, and the East Post Road, which ran along the island's east side, were built along ancient Native American hunting paths which allowed for easy development. The Common Lands stretched from the intersection of these two roads north in an irregular fashion to Harlem's boundary with the Commons.These two phenomena created a lack of interest in settling the land in the central part of the island. Traveling there was difficult, and the land either consisted of rocky outcroppings or low-lying overgrown marshland. All of this 'vast wasteland' was thus given to the government of New Amsterdam by the Dutch administrators in 1685 and reaffirmed by the English twice after they acquired the colony. Almost no one bought or rented the land from the colony, and it remained that way until the infancy of the United States, when the government of New York City inherited what had become known as the Common Lands.

At that time, New York City had little tax income, and so leveraged the Common Lands, which the Common Council, the city's governing body, believed could be developed. They contracted Casimir Theodor Goerck, a city surveyor, to survey the Common Lands and divide it into five acre lots that would then be sold at auction. Goerck, for his part, did the best he could with a massive task. By the December 1785, he had laid out a middle street, a rough estimation of today's Fifth Avenue, but almost none of the lots were of equal size. A handful of lots sold the following summer, but not many, most of which were in the extreme southern reaches of the Common Lands near the established city. In 1794, the Common Council again contracted Goerck to survey five-acre lots, but this time he was to also survey a road parallel to and on either side of the middle road. He was also to survey sixty-six-foot-wide east-west streets to allow for easier access. These roads would closely mirror Fourth and Sixth Avenues in the Commissioners plan of about a decade later, as would the east-west streets, although the Commissioners gave almost no credit to Goerck for the inspiration.

Holmes' 'Farm Maps'

In the early 19th century most of Manhattan was undeveloped farm lands, the property of wealthy landowners with claims dating to the Dutch period of New York's history. The northern 2/3rd Manhattan was dotted with farm lands and sprawling gentlemanly estates, many with great manor houses overlooking the Hudson River. The Commissioner's Plan of 1811 and the 1807 Commission Law, laid the street grid through many of these properties and gave the city the right to claim these lands under eminent domain, providing due compensation to the landowners. While this work occurred early in lower Manhattan, central and upper Manhattan were not formally acquired by the city until the mid-19th century.Holmes became fascinated by the early history of Manhattan real estate ownership, recognizing the wealth to be accrued by accurately understanding the history of city land ownership, division, and inheritance. Moreover, Holmes allied himself with the corrupt Tweed administration, assuring himself and his allies even greater wealth and political power from the eminent domain seizure of old Manhattan estates. Holmes created a series of maps, reminiscent of John Randall's 'Farm Maps', overlaid with property data, showing the borders of old estates, and notating the breakup of the lands among various heirs. The complex work of compiling the maps earned Holmes a fortune, with one newspaper suggesting on his death in 1887 that some of his individual maps were worth more than 30,000 USD. There is no complete carto-bibliography of Holmes' maps, but we believe there to be at least 50 maps, possibly more.

Provenance

This map was acquired as a part of a large collection of New York cadastral maps associated with the layer Ronald K. Brown, a Deed Commissioner operating in the late 19th and early 20th century with an office at 76 Nassau Street, New York - not far from Holmes' own office. Most of the maps in the collection, including the present map, bear Brown's stamp on the verso. The maps were passed to Dominic Anthony Trotta, a real estate agent working under Brown. Brown seems to have ceased business around 1919, but Trotta continued as a real estate agent, becoming a New York Tax Commissioner in 1934 under the Fiorello H. La Guardia administration. The maps remained with Trotta's heirs until our acquisition of the collection.Publication History and Census

This map was created and published by John Bute Holmes in 1874. Three examples are identified in the OCLC as part of institutional collections at Princeton University, the New York State Library, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The Museum of the City of New York also has an example in their collection and, although uncatalogued, we believe that the New York Public Library also has an example.Cartographer

John Bute Holmes (March 31, 1822 - May 21, 1887) was an Irish civil engineer, city surveyor, and mapmaker based in New York City in the middle to latter 19th century. Holmes was described as a 'short, stout man, with curly gray hair, a smooth face, and a short, thick neck.' Holmes' father-in-law supplied funds for him to immigrate to America in 1840 and shortly thereafter, in 1844, he established himself in New York City. He briefly returned to Europe before once again settling in New York City in 1848. Apparently, according to several New York Times articles dating to the 1870s, Holmes was a man of dubious personal and moral character. He was involved in several legal disputes most of which were associated with his outrageous - even by modern standards - womanizing. In 1857 he was convicted of forgery of a marriage document and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor at Sing Sing, of which he served 5 before wealthy associates interceded on his behalf for an early release. Holmes seems to have been married to several different women at the same time and to have had an unfortunate attraction to exceptionally young women - one of whom, 16 year old May Chamberlayne claimed to be his wife and sued him for 50,000 USD. On another occasion he was found guilty of killing Brooklyn policeman David Gourly with whose wife he 'had been intimate.' Another woman, Miss Abrams, who he hired as a housekeeper, was repeatedly attacked by Holmes and ultimately driven to madness and was consigned to Bellevue Hospital, where she died. Although he attempted to flee the country rather than face conviction for 4th degree manslaughter, he was ultimately arrested and served one year in prison. During the American Civil War he ran for Alderman of the First Ward, in New York. Despite his legal issues, Holmes was a man of considerable means, with a personal fortune estimated between 100,000 and 500,000 USD - a significant sum in the late 19th century. Much of his wealth is associated with a series of important cadastral maps produced between 1867 and 1875 while he was employed as a surveyor and civil engineer under the corrupt Tweed regime. When Holmes died of an 'apoplectic fit' there was considerable wrangling over his estate among his 7 heirs and 11 children. The cream of his estate where his maps, some of which were valued at more than 30,000 USD in 1887. Holmes lived on a large farm-estate in Fanwood New Jersey. More by this mapmaker...