This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1914 Japanese Serio-Comic Map of Asia and Europe during World War I

AhumorosAtlasoftheWorld-ryozotanaka-1914

Title

1914 (dated) 15.5 x 22 in (39.37 x 55.88 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

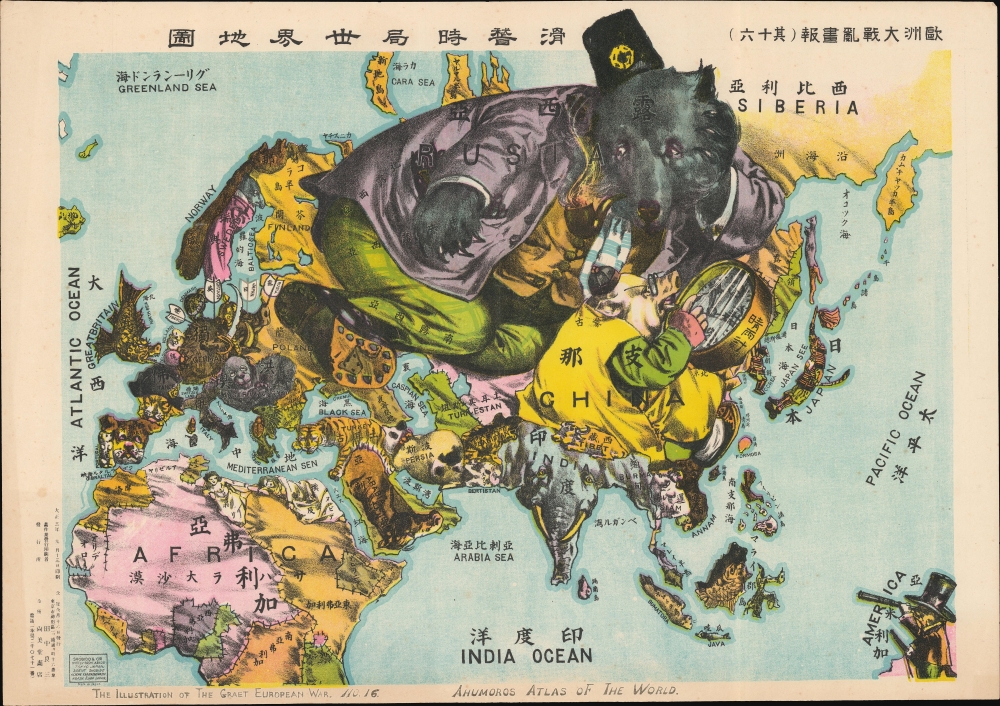

The map presents the Japanese perspective of the world at the outset of World War I (1914 - 1918). To understand the symbolism, attention needs to be focused on the map's three major players: Japan (Samurai), China (Pig), and Russia (Bear). At this time, Japan was beginning to see itself as the natural hegemon of East Asia. Its defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904 - 1905) and rapidly developing industrialization intensified pre-existing Japanese notions of cultural superiority.Accordingly, Japan is here represented as a samurai, notably one of only four human figures on the map and the only one portrayed as an armed warrior. (Nearby Korea is also in samurai armor but is positioned submissively towards Japan.) It looks west, towards China, Russia, and ultimately Europe.

China is a fat and myopic pig closely consulting a barometer. It is dressed in traditional clothing and looks east, with its back to the rest of the world. This is a critique of late Qing isolationism, backward thinking, and indecisiveness - the barometer is, after all, a way of predicting future weather. Despite this, China is large and wealthy, a fat swine primed for Japanese conquest.

To the north is Russia, represented as a well-dressed, rich, and powerful (if indolent) bear. Russia was Japan's primary adversary for control of East Asia, with the two nations maintaining long-standing disputes over influence and sovereignty in Manchuria, Sakhalin, and Korea. The bear's gaze has turned away from Asia, looking west toward the European conflict. It inches its boot into Eastern Europe, dominating Poland and Ukraine. Still, the map suggests that Russia may be mistaken in looking away from Japan, which recognizes an opportunity for further expansion and entrenchment in mainland Asia.

Europe, where World War I was raging, is nonetheless a secondary focus. Germany is represented as a boar, a dangerous animal to be sure, but ultimately prey. Arrows pierce its hide, having been launched from France, Britain (Gritain), Russia (Rusia), and Japan itself - a reference to August 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the war, when Japan issued an ultimatum to Germany demanding the withdrawal of German naval forces from Chinese and Japanese waters and the cession of the Kiautschou Bay (Jiaozhou Bay 膠州灣) Concession in China, centered on the port of Qingdao (青島). When Germany refused, Japan declared war and, at the time of publication, was besieging the German garrison at Qingdao, which would surrender to Japanese forces in early November.

Although seemingly a minor participant, in the lower right, the United States looks on. The U.S. is represented as a badger - a wily, solitary, and tenacious creature. It is dressed in modern clothing, holds a gun, and looks toward the Philippines with a telescope. Other than Japan, it is the only armed figure on the map. It speaks of the complex feelings the Japanese had toward the United States. On one hand, the 1853 arrival of Commodore Perry and the subsequent forced opening of Japan was a national humiliation. On the other hand, throughout the Meiji Period, Japan modeled its modernization and industrialization in part after the United States, which remained its primary trading partner despite being an ocean away. While the United States did maintain a colonial presence in the Philippines, Japan at the time did not have its eye on the Philippines, nor did it perceive the United States as a rival in the Pacific (the potential for conflict was smoothed over by the 1905 Taft-Katsura Agreement). Instead, there is a grudging respect for the United States, which, at this point, remained a neutral and distant observer.

Other parts of the map bear mention. India stands out as an enormous elephant, a revered creature in Japanese Buddhism, suggesting that Japan saw India more as an ally than a rival. Africa is a tapestry of loosely stitched rugs, the meaning of which is elusive, though, perhaps, is to suggest that the distant continent did not play into Japanese ambitions. The sole oddities are the reclining female figures occupying northern Egypt and Libya (Tripoli トリポリ). These are among the only human figures on the map (aside from Japan and Japanese-dominated Korea). Their robed forms suggest a reference to Hellenism and a nod to the much-revered (in Meiji and Taisho Japan) Ancient Greek contributions to philosophy, literature, art, and democratic governance. That these figures are in North Africa and not Greece is likely a reference to Greek Alexandria.

Chromolithography

Chromolithography, sometimes called oleography, is a color lithographic technique developed in the mid-19th century. The process uses multiple lithographic stones, one for each color, to yield a rich composite effect. Generally, a chromolithograph begins with a black basecoat upon which subsequent colors are layered. Some chromolithographs used 30 or more separate lithographic stones to achieve the desired effect. Chromolithograph color can be blended for even more dramatic results. The process became extremely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when it emerged as the dominant method of color printing. The vivid color chromolithography made it exceptionally effective for advertising and propaganda.Publication History and Census

This map was drawn by Ryōzō Tanaka (田中良三) and printed in chromolithograph by the Shobido Bookshop (尚美堂書店) of Tokyo September 13, 1914 (Taisho 3), and published three days later. Most text is in both English (although with numerous transliteration errors) and Japanese Kanji, clearly indicating that the audience for this map was not exclusively Japanese but also viewers in England and the United States. We note that Tanaka issued a similar map focused more specifically on Europe in the same year as part of the same series (see Geographicus: ahumoroswarmap-tanaka-1914). Notations in both Japanese and English suggest that it was part of a series (The Illustration of the Graet European War. No. 16. / 歐洲大戰亂畫報(其十六)), though the individual items in the series all appear to be quite rare now.Extremely rare. We note one example at the Texas War Records War Poster Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Otherwise, there are a few online digital references, all of which seem to be derived from one of two source images, neither of which are attributed. Not in OCLC or similar Japanese catalogs.

Cartographer

Ryōzō Tanaka (田中良三, January 16, 1874 - July 1, 1946) was a Japanese printer, publisher, illustrator, and bookseller active in Japan during the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. He was an important figure in the development of printing in 20th century Japan, including as part of the Shin-Hanga (新版画, 'new woodblock print') school, which revived traditional ukiyo-e techniques in the face of chromolithographic printing, which had become very popular in the late Meiji period. Tanaka was born in Kyoto, the second son of Haishi Hashimoto. He apprenticed under an Osaka bookseller Tanaka Jubei (田中重兵衛), marrying that individual's fourth daughter and taking the Tanaka name. Sometime in the 1890s, he relocated to Tokyo to open a branch office of the Tanaka Jubei firm. He soon thereafter (1897) opened his own business, the Tokyo Shobido Gakyou (東京尚美堂画局) book cart, in Kyobashi, Tokyo. It is said he started his book business with just 30 yen and 600 traditional ukiyo-e prints. By 1898, he acquired a physical location in the Kanda book district of Tokyo and began printing on his own account, pioneering Japanese chromolithography. Tanaka issued a series of serio-comic style maps in Japanese and English illustrating the events of World War I (1914 - 1818). In 1930, Tanaka shifted gears, becoming an adherent of the Shin-Hanga School and publishing some of its leading figures, including Hasui Kawase, Hiroaki Takahashi, and Mitsuitsu Tsuchiya. But he also continued to print and publish lithographic works, including a large number relating to Japan's military operations in China in the 1930s, the life of Japanese residents in China, and related matters. Most of Tanaka's original printing plates were destroyed in the March 1945 firebombing of Tokyo. After the war, Takaka's business was taken over by his eldest son, Tanaka Teizō (田中貞三), who attained some success. More by this mapmaker...