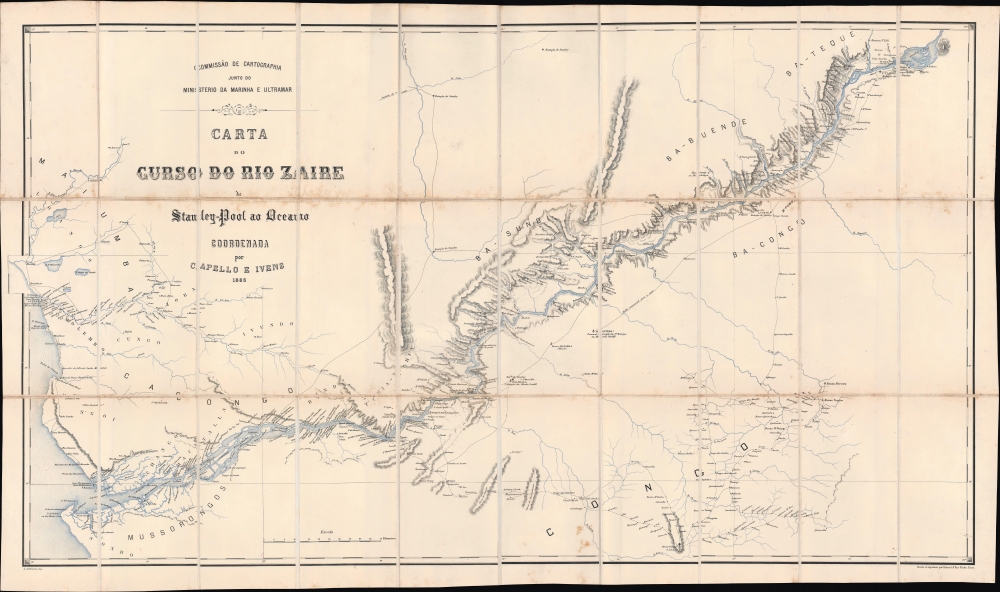

1883 Comissão Map of the Congo River: Capelo-Ivens Expedition

CongoRiver-comissaocartografia-1883

Title

1883 (dated) 25 x 44.5 in (63.5 x 113.03 cm) 1 : 400000

Description

A Closer Look

Coverage extends from the West African coast as far north as Massabi and as far south as the mouth of the Congo River, near the present-day city of Soyo in Angola. Rivers, lakes, mountain ranges, roads, villages, local kingdoms, and ethnic groups are noted. Portuguese knowledge of coastal areas was clearly more advanced due to their centuries-long presence there, such as along the Chiloango (Cacongo) River starting from Landana. Certain areas of the interior, where missions (missão) were established or where Portuguese explorers, traders, and troops had long traveled, such as São Salvador (M'banza-Kongo) at bottom right, were also familiar to Lisbon, though not necessarily well-mapped. Much of the information at right was more detailed than in any earlier European maps.The stops (estação) made by Stanley during his travels through the region are indicated throughout. Explanatory notes provide critical information about features, particularly the hazards on the notoriously dangerous Congo River (waterfalls, whirlpools, and rapids). The recently-established city of Léopoldville (N'Tamo, Kinshana) is labeled at top-right, near the confluence of Stanley Pool (Pool Malebo) and the Congo River. Due to the hazards on the Congo River, the city remained isolated and remote until the completion of the Matadi-Kinshasa Railway (Chemin de Fer du Congo) in 1898.

The Capelo-Ivens Expedition

Though hardly as famous as Stanley and Livingstone, perhaps due to their nationality and subsequent relative weakness of the Portuguese Empire, Hermenegildo Capelo (here as Capello), Roberto Ivens, and Alexandre de Serpa Pinto were nearly as important for European exploration of the African interior. As discussed below, Portugal was anxious about the viability of its presence in Africa in the closing decades of the 19th century, and feared encroachments by the British and other European powers. At the same time, the advance of European military technology and the tactic of establishing protectorates with friendly local rulers provided opportunities to expand Portuguese control into the interior parts of the continent.Luciano Cordeiro, the founder of the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, organized an expedition in 1877 with the aim of reaching the Kwango (Cuango) River, exploring areas to the south (near the present-day borders of Angola, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana), and eventually traveling straight across the continent to the Boer Republics or Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). More generally, the expedition aimed to find a reliable route between Angola and Mozambique to solidify Portugal's plans to create a Trans-African colony. The expedition, consisting of Capelo, Ivens, and Serpa Pinto, who later played an important role in the struggle with the British over the borders of Mozambique, quickly fell into disagreement and Serpa Pinto split off, exploring to the south around the Zambezi while Capelo and Ivens went north. After nearly three years of travel, the two men returned to Lisbon in March 1880, having charted the course of several rivers between the Congo and the Zambezi. They wrote about their expedition in the book De Benguela às Terras de Iaca (From Benguela to the Lands of Iaca). In the meantime, Serpa Pinto had reached Praetoria, completing the daunting task of crossing the continent, and also published a book, titled Como eu atravessei a África (translated as How I Crossed Africa). In 1884 - 1885, Capelo and Ivens undertook another expedition, this time crossing the continent, which was documented in their book De Angola à Contra-Costa (From Angola to the Other Coast).

European Scramble for Western Africa

Around the time this map was made, the Portuguese and rival European colonial powers vied for influence in Africa. Although the interior of Central Africa was poorly understood and foreboding, with violent death or disease the likely outcome for Europeans who traveled to the region, the well-publicized travels of Livingstone and Stanley opened the possibility for further European influence there. In 1876, King Leopold II of Belgium, who would later play a central and infamous role in the history of the region, convened the Brussels Geographic Conference, which established the innocuous-sounding International African Association. Nominally a humanitarian organization premised on ending the slave trade and promoting 'civilization' among the peoples of the Congo, the association in reality became an investment scheme for Leopold's grand project of exercising personal control over the entire region. It also financed expeditions to further explore and understand the Congo region, especially Stanley's long foray from 1879 to 1884, when he acted as an agent of Leopold. For their part, the Portuguese recognized this ruse early on and pressed for a general conference to resolve territorial disputes in Africa, what became the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885.At the Berlin Conference, the Portuguese laid out a plan they had been preparing for several years to establish an east-west corridor across central Africa between Angola and Mozambique, portrayed in the 1885 Mapa cor-de-rosa (Pink Map). The Portuguese gained the support of other European powers for their plan, except for Britain, whose subjects were advancing into these same areas. Although Britain was not especially interested in colonizing the Congo, their goal of establishing a string of colonies, or at least channels for trade, running 'from the Cape to Cairo' would be intersected by Portugal's claims.

Another product of the Berlin Conference was the creation of the Congo Free State, which grew out of the International Association of the Congo, a subsidiary of the International African Association. Although its borders were ill-defined, in part due to poor geographic information about the African interior, the Congo Free State effectively began at the 6th Parallel south, allowing it to take in Matadi, the last navigable port on the Congo River, towards bottom-center here. The private colony of Belgian King Leopold II, the Congo Free State became a horrific showcase of the worst atrocities of European colonialism.

Yet another outcome of the Berlin Conference was the doctrine of effective occupation, whereby territorial claims were primarily secured through the presence of troops and officials, regardless of historical knowledge of and interactions with a given region (which decidedly disadvantaged the Portuguese). In the wake of the Berlin Conference, rival colonial powers raced to establish effective occupation and claim territory. Although Portugal could not claim the Congo, Rhodesia, or what is now Zambia, thwarting their plan for a Trans-African colony, they did sign a treaty in 1885 with the Kingdom of N'Goyo to establish the Angolan exclave of Cabinda that included much of the coastline shown here, from the Bahia de Cabinda north to Massabi.

Portugal's 'Third Empire'

In the early 19th century, Portugal was no longer a great world power, and its empire was significantly reduced, especially after the independence of Brazil in 1822. But the empire did still maintain a string of colonies, the largest of which were Angola and Mozambique. Portuguese traders had been active along the coast of the Congo and Angola since the 15th century, followed closely by missionaries. Some Portuguese had ventured into the African interior in the early days of their colonial presence and set up estates, missions, and trading post-garrisons. However, settlers were few in number and generally intermarried with the local population to the point that they lost Portuguese identity, while the estates were operated like independent fiefdoms rather than a shared colonial enterprise. In Mozambique, the Portuguese inclination to try to force Christianity on their trading partners and use the presence of Muslim traders as an excuse for military campaigns also provoked opposition, while in Angola Portuguese rule was determined (and limited) by long and complicated relationships with several indigenous kingdoms, especially the Christian, Lusophone Kingdom of Kongo. For most of the colonial era, the Portuguese satisfied themselves with operating a handful of coastal outposts for exporting slaves to the New World. Therefore, Portugal's control was limited to ports and whatever control it claimed over the interior was exercised through intermediary local rulers, if at all.In the early-mid 19th century, the government launched a renewed effort to move colonists further inland and strengthen direct control over the interior. Angola underwent fundamental changes with the abolition of the slave trade in 1836. Although human trafficking and forced labor continued to be commonplace, the colonial ports of Angola (especially Luanda) shifted away from slave trading and developed new commercial markets that stretched far into the interior, allowing ports to grow considerably in the process (note the 'trilho commercial para a costa' at right-center here).

The 'Scramble for Africa' at the end of the century presented Portugal with both risks and opportunities. But they were incapable of challenging the British and had to grudgingly accept a secondary role among European colonial powers. Nevertheless, the British and Portuguese collaborated against Germany during the First World War. In the interwar period, with the threat of anti-colonial movements looming, Portugal moved towards a notion of 'pluricontinental' nationhood. However, with the wave of decolonization that followed World War II, Portugal faced the prospect of losing its colonies. The country's Prime Minister and de facto dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, categorically refused decolonization and aimed to crush guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). Counter-insurgency efforts were largely successful as a short-term solution, but failed to resolve underlying problems, and when Salazar's successor Marcelo Caetano was toppled in a coup in 1974, Portugal's empire quickly collapsed.

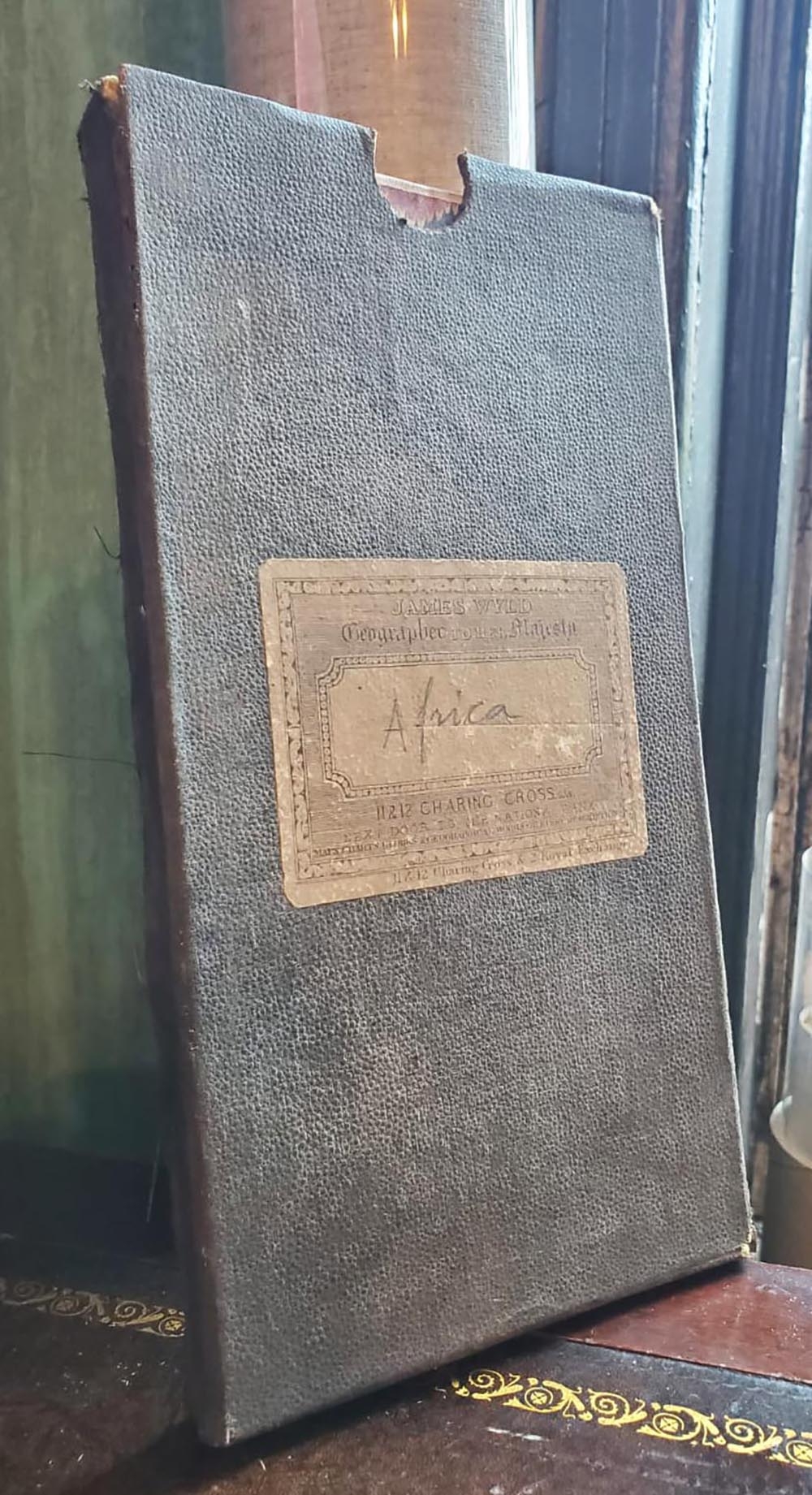

Publication History and Census

This map was drafted by Antonio Augusto de Oliveira of the Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias, based on information from Capelo and Ivens, and was engraved and printed by the Paris-based firm (Georges) Erhard in 1883. It is accompanied by a slipcase with the imprint of James Wyld, 'Geographer to His Majesty,' suggesting that it was distributed beyond Portugal. It is held by thirteen institutions worldwide and has no known history on the market.CartographerS

Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias (fl. c. 1883 - 1936), in its early years as 'Comissão de Cartographia das Colónias', was an office within the Ministério da Marinha e Ultramar tasked with surveying Portugal's colonies, primarily in Africa. It was dissolved in 1936 and replaced with Junta das Missões Geográficas e de Investigações Colonia. More by this mapmaker...

Georges Erhard Schièble (1823 – November 23, 1880) was a German printer active in Paris during the middle to late 19th century. Erhard was born in Forchheim, Baden-Württemberg, and relocated to Paris in his 16th year, where he apprenticed under his cousin, an engraver and mapmaker. In 1852, after 6 years with the Royal Printing Office, he started his own business. Around this time, he also became a naturalized French citizen. From his offices on Rue Bonaparte, he produced several important maps, and a detailed topography of Gaul for Napoleon III's History of Julius Caesar. In 1865 he took on larger offices expanding his operations to include a lithographic press. He was among the first to introduce printed color maps and pioneered photo-reduction, including the process known as Erhard reproduction. After Erhard's death in 1880, the firm was taken over by his sons and run under the imprint of 'Erhard Frères' until 1911. Learn More...