This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

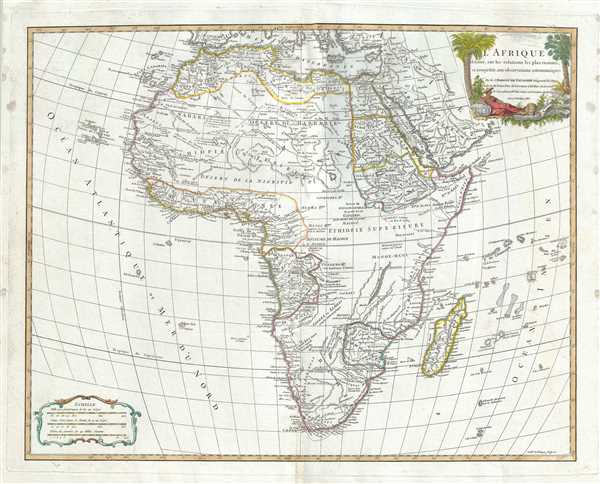

1783 Vaugondy Map of Africa

Afrique-vaugondy-1757

Title

1783 (dated) 19 x 24 in (48.26 x 60.96 cm) 1 : 20000000

Description

Like most maps of Africa from this period, the whole is rife with speculation. Vaugondy, unlike many of his contemporaries, attempts to limit his geographical analysis of the continent to those areas reported on in relatively recent times. Thus the White Nile, rather than turn east to meet with the Niger or flow south into the Ptolemaic Mountains of the Moon, merely tapers off into the unknown. Central Africa is largely left blank, although appears to be divided into several little known kingdoms: Monoe-mugi, Mujac, Gingir-Bomba, and Macoco, among others. The Sultanate of Zanzibar is given control of much of Eastern Africa from the Horn to the Zambesee River. Lake Malawi appears in recognizable but embryonic form with it supper terminus left unmapped and thus unknown. In West Africa the known kingdoms of Benin and Congo are mapped according to the early 18th century conventions. South Africa exhibits updated information associated with mid-18th century discoveries.

A highly decorative title cartouche appears in the top right quadrant. Drawn by Robert de Vaugondy and published in his Atlas Universal. The Atlas Universal was one of the first atlases based upon actual surveys. Therefore, this map is highly accurate (for the period) and has most contemporary town names correct, though historic names are, in many cases, incorrect or omitted.

Cartographer

Robert de Vaugondy (fl. c. 1716 - 1786) was French may publishing from run by brothers Gilles (1688 - 1766) and Didier (c. 1723 - 1786) Robert de Vaugondy. They were map publishers, engravers, and cartographers active in Paris during the mid-18th century. The father and son team were the inheritors to the important Nicolas Sanson (1600 - 1667) cartographic firm whose stock supplied much of their initial material. Graduating from Sanson's maps, Gilles, and more particularly Didier, began to produce their own substantial corpus. The Vaugondys were well-respected for the detail and accuracy of their maps, for which they capitalized on the resources of 18th-century Paris to compile the most accurate and fantasy-free maps possible. The Vaugondys compiled each map based on their own geographic knowledge, scholarly research, journals of contemporary explorers and missionaries, and direct astronomical observation. Moreover, unlike many cartographers of this period, they took pains to reference their sources. Nevertheless, even in 18th-century Paris, geographical knowledge was limited - especially regarding those unexplored portions of the world, including the poles, the Pacific Northwest of America, and the interiors of Africa, Australia, and South America. In these areas, the Vaugondys, like their rivals De L'Isle and Buache, must be considered speculative or positivist geographers. Speculative geography was a genre of mapmaking that evolved in Europe, particularly Paris, in the middle to late 18th century. Cartographers in this genre would fill in unknown lands with theories based on their knowledge of cartography, personal geographical theories, and often dubious primary source material gathered by explorers. This approach, which attempted to use the known to validate the unknown, naturally engendered rivalries. Vaugondy's feuds with other cartographers, most specifically Phillipe Buache, resulted in numerous conflicting papers presented before the Academie des Sciences, of which both were members. The era of speculative cartography effectively ended with the late 18th-century explorations of Captain Cook, Jean Francois de Galaup de La Perouse, and George Vancouver. After Didier died, his maps were acquired by Jean-Baptiste Fortin, who in 1787 sold them to Charles-François Delamarche (1740 - 1817). While Delamarche prospered from the Vaugondy maps, he defrauded Vaugondy's window Marie Louise Rosalie Dangy of her rightful inheritance and may even have killed her. More by this mapmaker...