1782 Pàges Map and Chart of Bombay / Mumbai, India

Bombay-pages-1782-2$800.00

Title

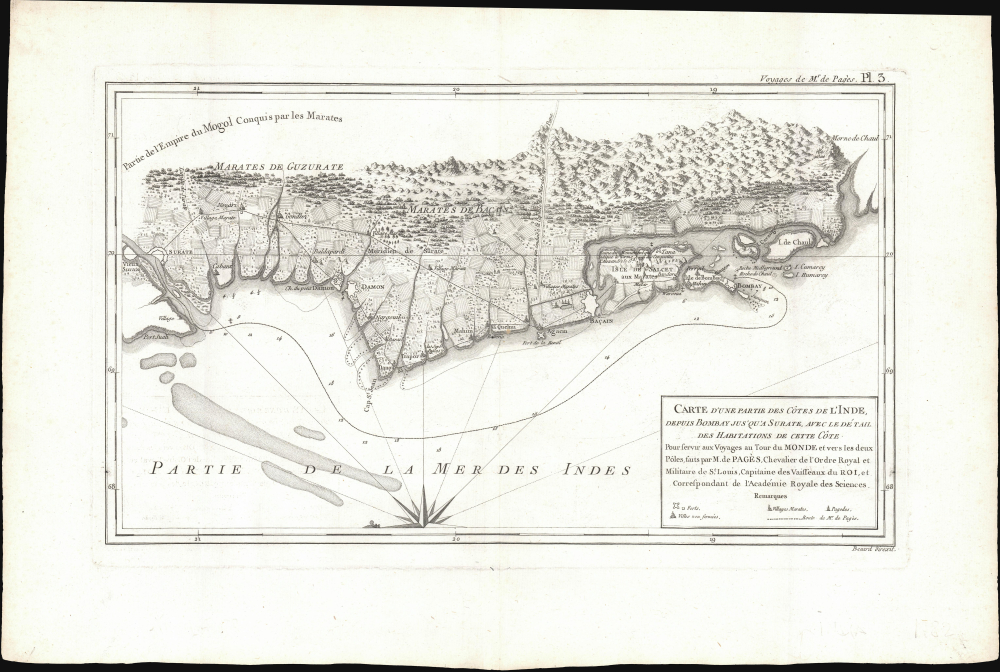

Carte d'Une Partie des Côtes de L'Inde, depuis Bombay jus'qu'a Surate, avec le détail des Habitations de cette Côte.

1782 (undated) 10.5 x 16.75 in (26.67 x 42.545 cm) 1 : 11000000

1782 (undated) 10.5 x 16.75 in (26.67 x 42.545 cm) 1 : 11000000

Description

This is a 1782 Pierre-Marie-François Pàges map of Bombay, India, and its vicinity. Produced near the end of the First Anglo-Maratha War, this map is uncommon in that it details not just the British fortification on Bombay Island, but also the surrounding Gujarat countryside and communities.

In the mid-1770s, the EIC in Bombay brazenly intervened in a succession struggle among the Marathas, backing Raghunathrao to succeed as Peshwa (Prime Minister) and signing with him the Treaty of Surat in 1775, which granted the EIC the island of Salsette and the fort of Bassein or Vasai (here as Baçain). However, the Bombay Presidency had not cleared this action with the Calcutta Council to which it was subordinate. This dispute within the EIC was set against the backdrop of greater efforts by the British Parliament to control the fantastically wealthy, powerful, and corrupt company, codified in the Regulating Act of 1773 (which subordinated Bombay to Calcutta) and the appointment of the hard-nosed, austere, Indophile Warren Hastings as Governor-General.

Therefore, in 1776, almost a year to the day after the Treaty of Surat, the EIC in Calcutta annulled that treaty and signed the Treaty of Purandhar with the Marathas. However, the Bombay Presidency refused to recognize this new treaty and gave refuge to Raghunathrao. This action led the Marathas to actually seek an alliance with the French, which raised British hackles across the board, especially given the tumultuous state of their colonies in North America, an important market for EIC tea and other goods. Although the alliance did not materialize, the Maratha attempt to grant the French a port on the west coast of India led the EIC in Bombay to launch an attack on the Marathas and try to install Raghunathrao as Peshwa. But this went horribly wrong, and the British force (which was, in fact, mostly composed of Indian sepoys) was forced to surrender at the Battle of Wadgaon in January 1779.

Afterwards, Hastings assembled reinforcements and sent them to Bombay to regain control of the situation, against the Marathas and his own wayward subordinates. After two years of inconclusive, see-sawing fighting, Hastings and the Marathas signed the Treaty of Salbai with Maratha commander Mahadaji Shinde, which mostly restored the status quo ante (though giving the British Salsette), committed the Marathas to fighting Mysore (which was nominally aligned with the Marathas but had battled both them and the EIC in the recent past), and dispelled any talks of a Maratha-French alliance or French outposts in Maratha territory. Superficially, this treaty was a confirmation of Maratha power and suited both sides, as they did not go to war again for another 20 years (a respectable interval given the frequent wars on the subcontinent at the time). But, in retrospect, the First Anglo-Maratha War has been seen as a lost opportunity for the Marathas to take advantage of British weakness (internal backlash against the EIC, distraction with the American War of Independence) and push them out of India. Moreover, the treaty heightened internal divisions within the Marathas, leaving them in a weaker position to resist the British in the future.

A Closer Look

Oriented to the east, coverage embraces from the fortified Gujarati city of Surat to the British Fort George on Bombay Island. Several Gujarati villages to the north and east of Bombay are noted. There are a few depth soundings marking approaches to Fort George. On Salcet (Salsette), the cartographer notes and partially illustrates a ruined monument marking the farthest point of Alexander the Great's conquests. We have found no other references to this monument.Historical Context

This map was published when First Anglo-Maratha War (1775-1782) was culminating. The conflict was as much a battle within the British East India Company (EIC) as between it and the Marathas. Although nominally vassals of the Mughals, the Maratha Confederacy or Maratha Empire had largely displaced the Mughals in central India and dominated what remained of the once-great empire. Thus, as British interest and influence expanded on the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century, it was in tandem with the rise of the Marathas, whom they eyed warily. Most importantly, the EIC wanted to prevent the Marathas from allying with the French, with whom they were competing for influence in India, quite successfully after sidelining them in the Battle of Plassey in 1757.In the mid-1770s, the EIC in Bombay brazenly intervened in a succession struggle among the Marathas, backing Raghunathrao to succeed as Peshwa (Prime Minister) and signing with him the Treaty of Surat in 1775, which granted the EIC the island of Salsette and the fort of Bassein or Vasai (here as Baçain). However, the Bombay Presidency had not cleared this action with the Calcutta Council to which it was subordinate. This dispute within the EIC was set against the backdrop of greater efforts by the British Parliament to control the fantastically wealthy, powerful, and corrupt company, codified in the Regulating Act of 1773 (which subordinated Bombay to Calcutta) and the appointment of the hard-nosed, austere, Indophile Warren Hastings as Governor-General.

Therefore, in 1776, almost a year to the day after the Treaty of Surat, the EIC in Calcutta annulled that treaty and signed the Treaty of Purandhar with the Marathas. However, the Bombay Presidency refused to recognize this new treaty and gave refuge to Raghunathrao. This action led the Marathas to actually seek an alliance with the French, which raised British hackles across the board, especially given the tumultuous state of their colonies in North America, an important market for EIC tea and other goods. Although the alliance did not materialize, the Maratha attempt to grant the French a port on the west coast of India led the EIC in Bombay to launch an attack on the Marathas and try to install Raghunathrao as Peshwa. But this went horribly wrong, and the British force (which was, in fact, mostly composed of Indian sepoys) was forced to surrender at the Battle of Wadgaon in January 1779.

Afterwards, Hastings assembled reinforcements and sent them to Bombay to regain control of the situation, against the Marathas and his own wayward subordinates. After two years of inconclusive, see-sawing fighting, Hastings and the Marathas signed the Treaty of Salbai with Maratha commander Mahadaji Shinde, which mostly restored the status quo ante (though giving the British Salsette), committed the Marathas to fighting Mysore (which was nominally aligned with the Marathas but had battled both them and the EIC in the recent past), and dispelled any talks of a Maratha-French alliance or French outposts in Maratha territory. Superficially, this treaty was a confirmation of Maratha power and suited both sides, as they did not go to war again for another 20 years (a respectable interval given the frequent wars on the subcontinent at the time). But, in retrospect, the First Anglo-Maratha War has been seen as a lost opportunity for the Marathas to take advantage of British weakness (internal backlash against the EIC, distraction with the American War of Independence) and push them out of India. Moreover, the treaty heightened internal divisions within the Marathas, leaving them in a weaker position to resist the British in the future.

Pàges Voyage (1767 - 1776)

Pierre-Marie-François Pàges, a French naval officer and explorer, undertook an ambitious 1767 - 1776 voyage that circumnavigated the globe and explored a vast range of territories. He left France for the Caribbean in 1767, exploring the West Indies and then traveling through Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley in North America. Pàges crossed overland through Texas, where he documented the lives of indigenous peoples, landscapes, and wildlife. From there, he sailed across the Pacific, visiting the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), and China, before making his way to India and traveling overland through Persia, Syria, and the Middle East. After years of exploration, he returned to France in 1776. Pàges recorded his experiences and observations in his 1782 Voyages Autour du Monde et vers les Deux Pôles ('Voyages Around the World and to the Two Poles'), which offered detailed accounts of the cultures, environments, and political conditions of the regions he visited. His work reflected the spirit of the Enlightenment, emphasizing scientific inquiry, curiosity, and interconnectedness.Publication History and Census

This map was engraved by Robert Benard for publication in Pàges 1782 Voyages Autour du Monde et vers les Deux Pôles. The separate map is not cataloged separately, but the full work is well represented institutionally.Cartographer

Robert Bénard (1734 - c. 1785) was a French engraver. Born in Paris, Bénard is best known for supplying a significant number of plates (at least 1,800) for the Encyclopédie published by Diderot and Alembert. He also is remembered for his work with the Académie des Sciences, most notably the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers More by this mapmaker...

Source

Pàges, P., Voyages Autour du Monde et vers les Deux Poles, par Terre et par Mer pendant les Années 1767, 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1773, 1774 et 1776, (Paris: Chez Moutard) 1782.

Condition

Excellent.

References

Rumsey 11230.004. Dalrymple, W., The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire, (Bloomsbury: London) 2019.