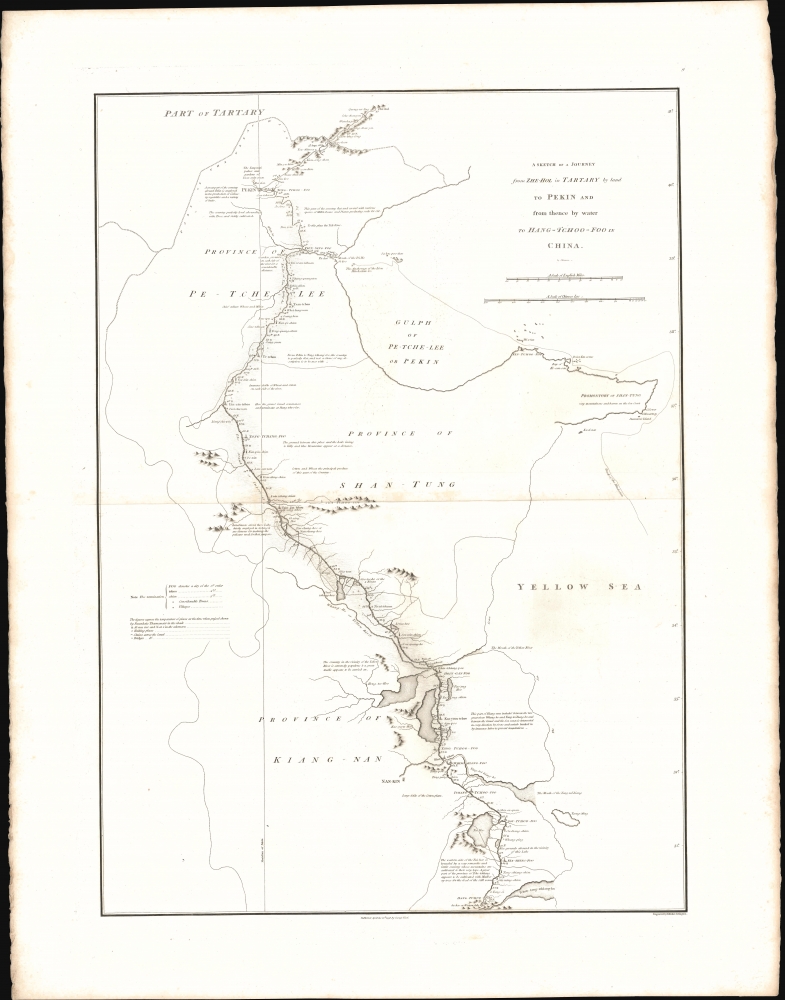

1796 Barrow Map of the Grand Canal, China, during the Macartney Mission

ChinaMacartney-barrow-1796

Title

1796 (dated) 25.5 x 18 in (64.77 x 45.72 cm) 1 : 2000000

Description

A Closer Look

The map traces the route taken by Macartney following his embassy's meetings with the Qianlong Emperor at the Qing Summer Palace at Chengde. The location of the meeting - at the Summer Palace instead of Beijing - was one of the early warning signs that the embassy was off to a bad start. After leaving Chengde, the British mission traveled southwest through the Great Wall to Beijing, and then down the Hai River (also known as White River or Baihe, transliterated here as 'Pei Ho') to Tianjin. From there, the mission traversed the Grand Canal through Shandong Province to Jinan (Tsin-jin-tchoo) and on to the great trading cities of Jiangnan: Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Changzhou, Suzhou, and eventually Hangzhou, where the Grand Canal ends.Along the way, Barrow notes the dates and notes on the terrain and economy. A small legend at left indicates symbols for cities of different sizes with transliterations of their Chinese terms (foo 府, tchoo 州, shien 縣) as well as features along the canal. Mountains, rivers, lakes, and other features are noted throughout, including the Great Wall and the course of the embassy's ships (the Lion and Hindostan), which were too large to travel along the canal.

The Macartney Mission

The Macartney Mission, or the Macartney Embassy, was a diplomatic mission by Great Britain to the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty meant to expand British trading rights in China and establish a permanent embassy in Beijing. Thirty-five years earlier, British traders of the East India Company (EIC) were confined to trading with an officially sanctioned set of Chinese traders in Guangzhou (Canton). Although the Canton System was profitable, the EIC found it too cumbersome and restrictive while also feeling that a direct line to Beijing was necessary to resolve disputes (rather than working through several layers of intermediaries and bureaucrats). A mission led by Charles Cathcart had been sent to Beijing in 1787, but Cathcart died before reaching China and the embassy was abandoned.George Macartney's mission left Britain in September 1792 with a retinue of translators (including Chinese Catholic priests trained in Italy), painters, secretaries, scholars, and scientists. The well-equipped and impressive embassy traveled via Madeira, Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, the Cape of Good Hope, Indonesia, and Macau, before moving up the Chinese coast and reaching Beijing on August 21, 1793. Macartney's second in command was George Leonard Staunton who served as the expedition's secretary and chronicler. Staunton's 11-year-old son, George Thomas Staunton, nominally the ambassador's page, learned Chinese during the voyage and served as a translator for the mission alongside the Catholic priests Paolo Zhou (周保羅) and Jacobus Li Zibiao (李自標). The younger Staunton later became chief of the East India Company's factory at Guangzhou, translated works between Chinese and English, and helped found the Royal Asiatic Society (Barrow, who had been the younger Staunton's mathematics teacher, also picked up enough Chinese to help translate and became something of a Sinologist in the years after the embassy's return).

The embassy was poorly managed from the beginning and, despite considerable pomp from the English perspective, appeared poor and rag-tag to the Qianlong Emperor. Partly through lack of preparation, partly through arrogance, and partly due to the Emperor's distaste for the British, the embassy failed in all its primary objectives. This disappointing result was compounded by a now-famous letter from Qianlong to King George III that chided the British monarch for his audacity in making demands of the Qing and his ignorance of the Chinese system, ending with a reminder not to treat Chinese laws and regulations lightly, punctuated with the memorable phrase 'Tremblingly obey and show no negligence!' In the British and Western accounts of the mission, this letter and the protracted dispute on whether Macartney would kowtow to the Emperor, as was standard, or simply kneel, as he would to his own monarch, was seen as evidence of the Qing's obsession with spectacle and ritual over practicality and substance.

Macartney's Mission highlighted cultural misunderstandings between China and the West, and has often been taken as a turning point in Chinese history. Qianlong's dismissal of foreign objects as mere toys and his insistence of the centrality of China in the world's hierarchy of kingdoms have been seen as sign of Chinese intransigence and a harbinger of China's decline in the 19th century. After the British left, Qianlong commented on the quality of their weapons, but showed no interest in a small model steam engine or other technically complex gifts the Brits had brought (Barrow, along with the scientist James Dinwiddie, was tasked with managing and delivering these gifts to the Emperor).

At the time the embassy visited, Qianlong had been in power for nearly sixty years and increasingly turned over management of the empire to a small group of self-serving officials, particularly Heshen, remembered as the most corrupt official in Chinese history. In the countryside, overpopulation and famine provoked millenarian religious movements and uprisings. On the southern coast, the British East India Company began importing opium in larger and larger quantities, eventually causing a severe social and economic crisis in southern China. In retrospect, both Chinese and foreign historians of every ideological bent have seen the Macartney Mission as a missed opportunity for the Qing to recognize the tremendous changes taking place in Europe and address underlying problems that would eventually sink the empire.

For their part, the British gained considerable direct knowledge of the country (earlier knowledge was usually second-hand from Catholic missionaries) and began to perceive the Qing Court as sclerotic and intransigent, the narrative which has come to define them in most subsequent histories. Although Macartney and his retinue witnessed an extremely wealthy and productive empire, they also correctly sensed that it was tottering and could be defeated by British forces in a military conflict (which Macartney nonetheless advised against).

Publication History and Census

This map was drawn by John Barrow, engraved by Benjamin Baker, and printed in 1796 to accompany George Staunton's 1797 An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China, published by G. Nicol in London. It is only cataloged at the University of California Berkeley, the British Library, the National Library of Scotland, and the National Library of Australia, while the entire Account is listed among the holdings of 13 institutions in North America and Europe in the OCLC.CartographerS

John Barrow (June 19, 1764 – November 23, 1848) was an English statesman, cartographer, and writer active in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Barrow was born in the village of Dragley Beck, in Ulverston, Cumbria. His first recorded work was as a superintending clerk at a Liverpool iron foundry, but by his early 20s, transitioned to teaching mathematics at a private school in Greenwich. One of his pupils, the young son of Sir George Leonard Staunton, favored him and he was introduced to Lord George Macarteny. Barrow accompanied Macartney as a comptroller of household, on his 1792-1794, embassy to China. Having acquitted himself well, Barrow was hired by Macartney as private secretary on a political mission to the newly acquired Cape Colony, South Africa. Barrow was given the difficult task of reconciling Boer settlers with the indigenous African population. In the course of this voyage he traveled throughout the Cape Colony, coming to know that country well. There he married botanical artist Anna Maria Truter, and, in 1800, acquired a home with the intention of settling in Cape Town. Following the 1802 Peace of Amiens, the British surrendered the colony and Barrow returned to England where he was appointed Second Secretary to the Admiralty, a post he held with honor for the subsequent 40 years. In his position at the Admiralty Barrow promoted various voyages of discovery, including those of John Ross, William Edward Parry, James Clark Ross, and John Franklin. The Barrow Strait in the Canadian Arctic as well as Point Barrow and the city of Barrow in Alaska are named after him. He is reputed to have been the initial proposer of St Helena as the new place of exile for Napoleon Bonaparte following the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He was a member of the Royal Society and the Raleigh Club, a forerunner of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1835 Sir Robert Peel conferred upon him a baronetcy. More by this mapmaker...

George Nicol (1740 - June 25, 1828) was a Scottish bookseller and publisher active in in 18th-century London. Nicol was born in Scotland, but relocated to London in 1769 to work with his uncle, the Strand bookseller David Wilson (17?? - 1777). The two eventually became full business partners, enjoying immense success. When Wilson died in 1777, Nichol took over the business in full. In 1781, Nicol was appointed official bookseller to King George III, a position he maintained until 1820. In 1787 he relocated to Pall Mall, acquiring 51 and 58 Pall Mall, one as a shop and the other as living quarters. Around 1800, his son George Nicol joined the firm, and it was renamed George and William Nicol. When the elder Nichol died in 1828, the firm continued as William Nicol until 1855. Learn More...

Joseph Baker (1767 - 1817) was a British naval officer and explorer best known for his service under George Vancouver during the historical Vancouver expedition to map the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver was born in the Welsh border counties. He joined the Royal Navy in 1787 where he met and befriended then-Lieutenant George Vancouver and then-Midshipman Peter Puget. When Vancouver was commissioned to complete the exploration of the American Northwest Coast, he chose Baker as he 3rd Lieutenant and Puget as his 2nd Lieutenant. During the course of the expedition Baker was assigned the task of converting surveys into working maps and his name appears on many of Vancouver's most important maps, including the first complete map of the Hawaiian Islands. Baker, along with the expedition's naturalist Archibald Menzies, completed the first recorded ascent of Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano. Mt. Baker, in modern day Washington, is also named after him. In his journals Vancouver wrote admiringly of Baker's work:…my third Lieutenant Mr. Baker had undertaken to copy and embellish, and who, in point of accuracy, neatness, and such dispatch as circumstances admitted, certainly excelled in a very high degree.

Following the Vancouver expedition Baker briefly retired from naval service until being recalled and made Captain in 1808. Assigned to the ship HMS Tartar, Baker was charged with escort duty in the Baltic. There, in a series of skirmishes with Danish privateers, Baker fell afoul of his British superiors and was court-martialed. Although acquitted of the court martial, Baker never again served in the Royal Navy. He retired to Presteigne where he maintained a long standing friendship to Puget, who moved to the same town on his own retirement. Learn More...