This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1568 Münster View of Edinburgh, Scotland

Edinburgh-munster-1550

Title

1550 (undated) 10 x 7.25 in (25.4 x 18.415 cm)

Description

The View

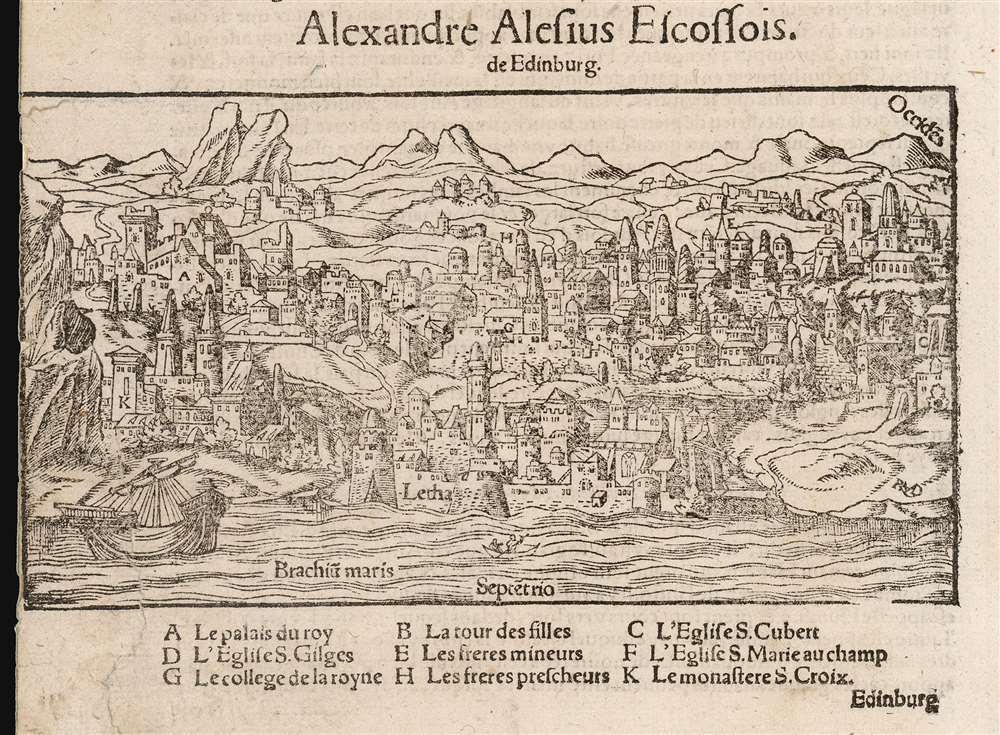

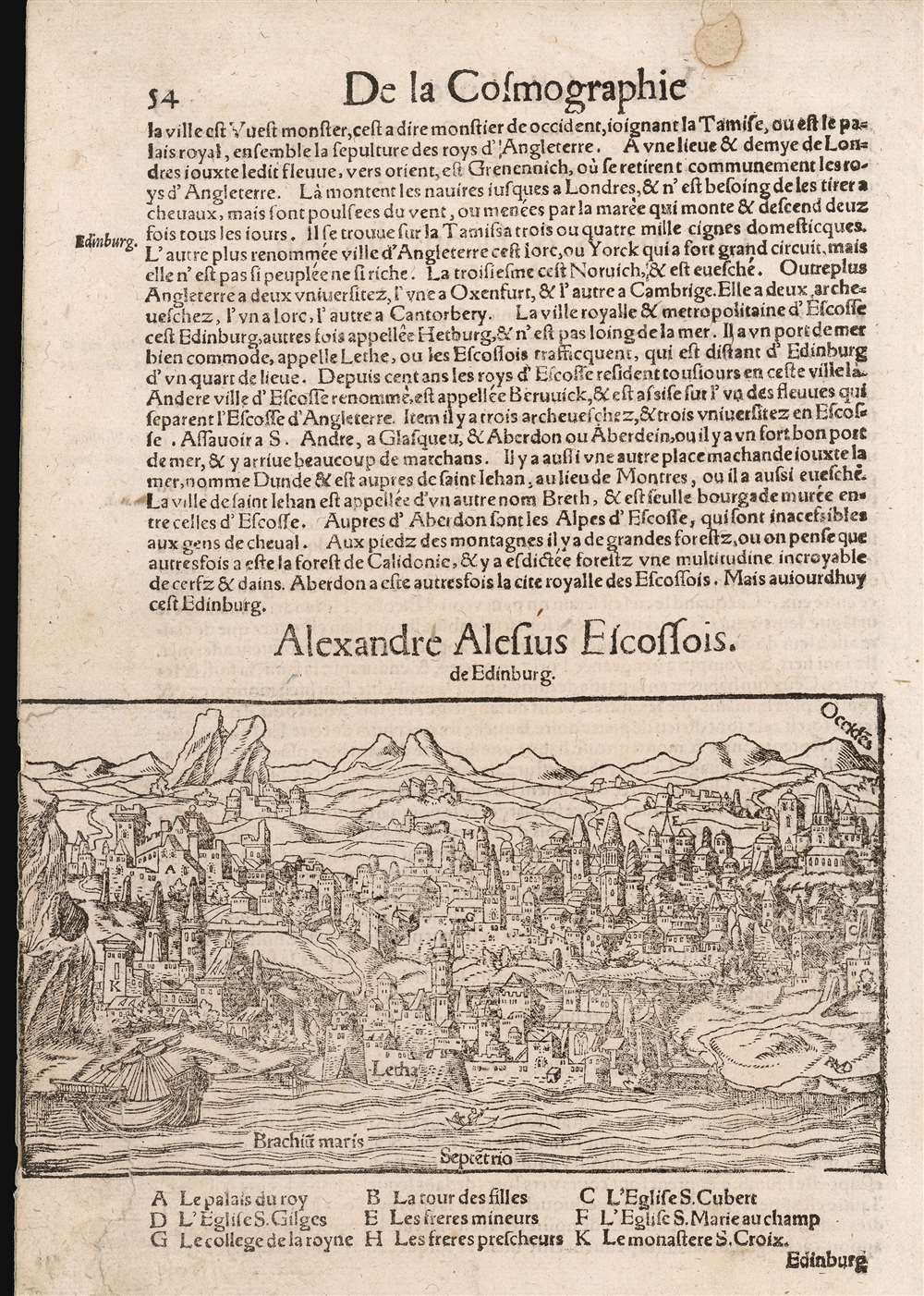

The view presents Edinburgh as viewed from the north, looking south. This presents the city as it would be seen from the Firth of Forth, here named descriptively as 'Brachiū maris,' or 'an arm of the sea.' The view centers on Edinburgh's port district, the Lethe, which is here named. The Scottish Royal Palace, St. Giles Cathedral, and other key features are keyed with letters to an identifying table below the view. Overall, the view conveys the rugged, hilly topography of the city, as well as its medieval walls. A sailing ship lies off the Lethe at anchor, and a boat can be seen poling through the waters of the Firth.A View based on Firsthand Report

Münster's Cosmographia is notable for the number of maps and views which depict their subjects for the first time in print, often from residents of the regions shown. The present work was credited to Alexander Ales (April 23, 1500 – March 17, 1565), a Scottish theologian and humanist whose embrace of Lutheranism led him to flee to Germany from Scotland, where he was tried for heresy, sentenced to death, and whose refusal even after these sentences to cease advocacy for the right of Scot laity to read the Bible in the vernacular would win his excommunication by the Archbishop of St. Andrews. It is not known when Ales and Münster met, but his long tenure in Frankfurt an der Oder would have given ample opportunity. While the woodcut view here was composed by artist and formschneiderHans Rudolf Manuel Deutsch, the placement of landmarks strongly suggests that Ales provided at least a verbal description of the city as a model, or perhaps even a sketch.Adding to the Cosmographia

Münster constantly labored to build the work until his death by plague in 1552, both adding to the text as well as ordering the production of improved city views and decorative woodcuts. 1550 saw the addition of this cut, along with many other maps and views to appear in the body of the work, as opposed to the 'foretext' maps that appeared from the book's inception.Publication History and Census

Munster's Cosmographia was a popular work, and as many as fifty thousand were printed. While many of these did not survive, individual maps do appear on the market from time to time. The separate woodcut is listed in OCLC by only two institutional collections, although the full work is well represented. The pagination of this specific example is consistent with the 1568 French edition of La cosmographie universelle.CartographerS

Sebastian Münster (January 20, 1488 - May 26, 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, Hebrew scholar and humanist. He was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518, after which he was appointed to the University of Basel in 1527. As Professor of Hebrew, he edited the Hebrew Bible, accompanied by a Latin translation. In 1540 he published a Latin edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, which presented the ancient cartographer's 2nd century geographical data supplemented systematically with maps of the modern world. This was followed by what can be considered his principal work, the Cosmographia. First issued in 1544, this was the earliest German description of the modern world. It would become the go-to book for any literate layperson who wished to know about anywhere that was further than a day's journey from home. In preparation for his work on Cosmographia, Münster reached out to humanists around Europe and especially within the Holy Roman Empire, enlisting colleagues to provide him with up-to-date maps and views of their countries and cities, with the result that the book contains a disproportionate number of maps providing the first modern depictions of the areas they depict. Münster, as a religious man, was not producing a travel guide. Just as his work in ancient languages was intended to provide his students with as direct a connection as possible to scriptural revelation, his object in producing Cosmographia was to provide the reader with a description of all of creation: a further means of gaining revelation. The book, unsurprisingly, proved popular and was reissued in numerous editions and languages including Latin, French, Italian, and Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Münster's death of the plague in 1552. Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, passing through 24 editions between 1544 and 1628. This success was due in part to its fascinating woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). Münster's work was highly influential in reviving classical geography in 16th century Europe, and providing the intellectual foundations for the production of later compilations of cartographic work, such as Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Münster's output includes a small format 1536 map of Europe; the 1532 Grynaeus map of the world is also attributed to him. His non-geographical output includes Dictionarium trilingue in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and his 1537 Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Most of Munster's work was published by his stepson, Heinrich Petri (Henricus Petrus), and his son Sebastian Henric Petri. More by this mapmaker...

Alexander Ales (April 23 1500 – March 17, 1565) was a Scottish theologian and humanist who emigrated to Germany to became a Lutheran supporter of the Augsburg Confession. Her was born in Edinburgh, studied at St. Andrews, and became a priest. As a University priest, he was a vocal advocate of Renaissance humanism, but was also vigorously anti-Protestant. In 1528 he had a traumatic conversion: he had been chosen to debate the Lutheran Pastor and former Abbot Rev. Patrick Hamilton, in an effort to convince Hamilton of the errors of Lutheranism. The debate utterly failed its purpose: Hamilton did not recant, and was sentenced to burn at the stake. Ales, impressed both by Hamilton's theological arguments and the courage with which he faced his death at the stake, immediately began to preach Lutheranism. He was imprisoned, but escaped - both from prison and Scotland, fleeing to Germany in 1532. (In Scotland, he was tried in absentia for heresy, and sentenced to death.) His travels brough him to Wittenberg, where he became friends with Martin Luther and signed the Augsburg confession, but he did not turn his back on Scotland, sending an open letter to King James V of Scotland defending the right of the laity to read the Bible. Further letters resulted in his excommunication by the Archbishop of St. Andrews. Affairs changed when King Henry VIII of England (1509–47) declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England: Ales visited England and was received by the King and his Protestand advisers, including Cromwell. He was part of the court of Anne Boleyn, and was in London during her trial, and execution; he had not believed that Boleyn was not guilty of any of the other crimes for she was executed and, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, Alesius wrote a letter to the new Queen detailing his memories of Boleyn, her mother.

Cromwell's support won Ales a theological lecture at Queens' College, Cambridge, but his expositions of the Hebrew psalms led to the Catholic factions of the college preventing him from continuing. He returned to London, where for some time he practiced as a physician, taking part in theological debates from time to time. Cromwell's fall from the King's favor in 1539 forced Ales to flee again to Germany where he would be appointed to a theological chair at the university of Frankfurt an der Oder. He would visit England briefly during the reign of Edward VI's reign, but would spend most of the rest of his life in Leipzig as Rector of the University.

Though a prolific writer, his works were virtually all of a religious nature, largely focused on the advocacy for vernacular translation of scripture. It is not known when precisely he and Sebastian Münster corresponded, but at some point prior to 1550 he certainly did: Münster's description of Scotland in his Cosmographia relied on Ales' report, and the woodcut view appearing in editions of the work after 1550 was creditied to the Scot theologian.

Learn More...

Heinrich Petri (1508 - 1579) and his son Sebastian Henric Petri (1545 – 1627) were printers based in Basel, Switzerland. Heinrich was the son of the printer Adam Petri and Anna Selber. After Adam died in 1527, Anna married the humanist and geographer Sebastian Münster - one of Adam's collaborators. Sebastian contracted his stepson, Henricus Petri (Petrus), to print editions of his wildly popular Cosmographia. Later Petri, brought his son, Sebastian Henric Petri, into the family business. Their firm was known as the Officina Henricpetrina. In addition to the Cosmographia, they also published a number of other seminal works including the 1566 second edition of Nicolaus Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium and Georg Joachim Rheticus's Narratio. Learn More...