1671 Kircher / Burgundus North Polar Projection World Map, Geographical Sundial

Geographicum-kircher-1671

Title

1671 (undated) 9.75 x 15.25 in (24.765 x 38.735 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

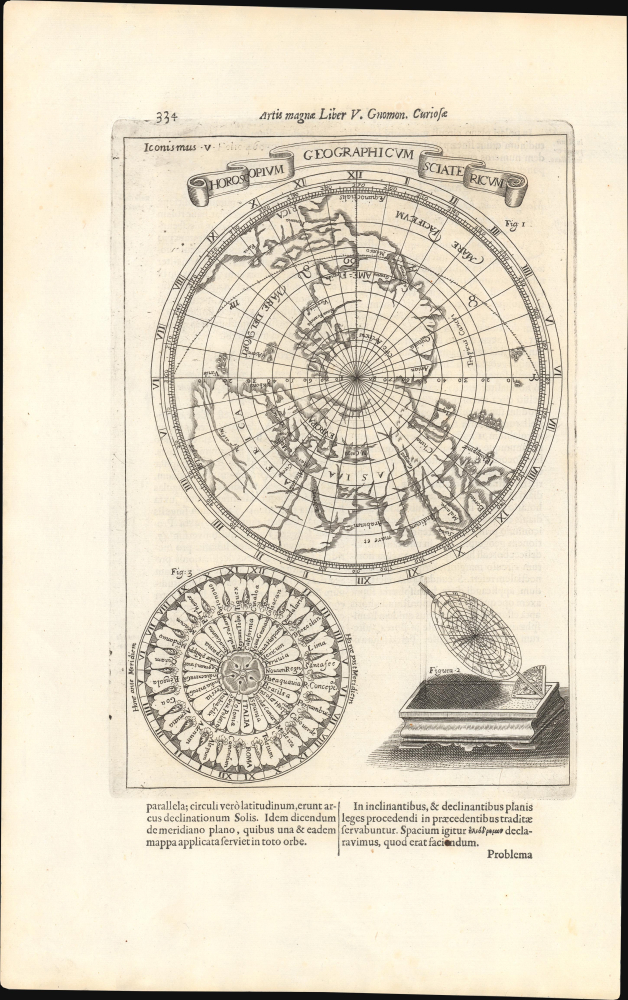

Most of the printed portion of the sheet is taken up by a map of the world with a North Polar projection, which is interesting in itself for reflecting the uncertain state of geographic knowledge of the Arctic at the time. (Kircher is non-committal on the possibility of a Northwest Passage.) The map also features additional curious elements, such as the extremely long Niger and Ganges Rivers, as well as the labeling of Virginia, Florida, and California. A dashed line tracks across the northern part of the Americas, marked with zodiac symbols. This work contrasts well with Kircher's stunning maps of the interior of the world, covering volcanoes and water systems (previously sold by us).Below the map are two circular representations of what Kircher would call a 'sciathericon' or 'sciatericum,' referring to the use of shadows cast by the sun in determining not only the time of day but additional meaning as well. It is related to his broader fascination with light, shadow, and circular motion, as laid out in the book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (discussed below), in which this sheet appeared. Figure 2, at the bottom right, is a projection of the map above, viewed two-dimensionally from a side oblique angle, allowing the shadows it would cast to be seen. Figure 3, at the bottom left, is a chronological chart with countries and cities recorded along with their relative times ante or post meridian. Notably, it begins in Mexico (New Granada) and Syria. Text below and on the verso further explains Kircher's notion of a 'horoscopium geographicum sciatericum.'

Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae

This sheet appeared in Kircher's work Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae… ('The Great Art of Light and Shadow'), which was an important milestone in the history of science, being the first published work in Europe on illumination and the projection of images. The book also included the first published illustration of Saturn and one of the first published descriptions of a microscope, of Kircher's own design, which he called a 'smicroscopus.' Otherwise, there were hundreds of pages of text, diagrams, illustrations, and maps dealing with all facets of light, color, vision, and optics. Soon before Ars Magna…, Kircher published a book on magnetism (Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica), and the titles of the two books made a playful duo. They also fit into Kircher's broader philosophical framework, in which magnetism played a central role. (His first book, Ars Magnesia, published in 1631, was on the topic.)The name of this book was also influenced by the 13th century Majorcan thinker Ramon Llull (c. 1232 - 1316), whose philosophical system dubbed 'Ars,' set out in a book titled Ars Magna, heavily influenced Kircher and others, particularly alchemists, in the early modern period. Llull's system, rooted in combinatorics and numerology, was itself strongly influenced by Arabic astronomy and combinations of the Hebrew alphabet from Kabbalah traditions. Kircher was also clearly impacted by Llull's fascination with 'volvelles,' concentric discs with concepts written on them that could be rotated into different alignments to divine meaning.

Kircher was so taken with the phrase 'Ars Magna' that he used it in the titles of two of his other works, Musurgia Universalis sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni (1650) and Ars Magna Sciendi Sive Combinatoria (1669), the latter being in many ways the culmination of his life's thought. Taken as a whole, the work is indicative of the state of European intellectual history at the time, highly curious about the outside world, developing new techniques and practices for experimentation, and aiming to develop a comprehensive system of thought that combined elements of what would later be divided into science proper and pseudo-science.

Publication History and Census

This diagram was engraved by frequent Kircher collaborator Petrus Miotte Burgundus and appeared in the 1671 edition of Kircher's Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, published by Jansson in Amsterdam. The present edition of the sheet is not independently cataloged in the OCLC, while the 1646 edition published in Rome is cataloged at the Université Paris Cité. The entire Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae is well-represented in institutional collections, but only occasionally appears on the market, generally at high-end auction houses.CartographerS

Athanasius Kircher (c. 1601 - 1680) was a 17th century German Jesuit scholar and one of the most respected and remarkable men of his time. A master of languages, mathematics, science, geography, physics and oriental studies, many consider Kircher to be 'the last true Renaissance man.' Kircher attained almost global fame in his lifetime for his numerous scholarly publications. Indeed, Kircher was the first documented scholar able to fully support himself on his own work, which, in his case, included some forty volumes on diverse fields. As a Catholic in Germany, Kircher was frequently at odds with the rising powers of Protestantism. Consequently, in 1628 he joined the priesthood and after extensive world travels eventually settled in Rome. There he was employed as a Professor of Mathematics and Oriental Languages at the Collegio Romano. Inspired by the eruption of Vesuvius in 1637 and the two weeks of earthquakes that shook Calabria in 1638, Kircher turned his considerable intellect to the natural world. Kircher's research into Geography and Oceanography culminated in the postulation that tides and currents were caused by water moving to and from a great subterranean ocean. Kircher published his geographic work in the important 1664 Mundus Subterraneus, which in addition to several world and oceanic charts, included a fascinating map of Atlantis. Kircher is nonetheless, not unimpeachable. One anecdote tells how a rival scholar presented Kircher with a manufactured gibberish manuscript he claimed to be an recently discovered ancient Egyptian text in need of translation. Kircher produced the translation instantly. In addition to his significance as a scholar, Kircher is best known for his invention of the Magic Lantern, precursor to modern cinema. He also founded the Museum Kircherianum in Rome. More by this mapmaker...

Jan Jansson or Johannes Janssonius (1588 - 1664) was born in Arnhem, Holland. He was the son of a printer and bookseller and in 1612 married into the cartographically prominent Hondius family. Following his marriage he moved to Amsterdam where he worked as a book publisher. It was not until 1616 that Jansson produced his first maps, most of which were heavily influenced by Blaeu. In the mid 1630s Jansson partnered with his brother-in-law, Henricus Hondius, to produce his important work, the eleven volume Atlas Major. About this time, Jansson's name also begins to appear on Hondius reissues of notable Mercator/Hondius atlases. Jansson's last major work was his issue of the 1646 full edition of Jansson's English Country Maps. Following Jansson's death in 1664 the company was taken over by Jansson's brother-in-law Johannes Waesberger. Waesberger adopted the name of Jansonius and published a new Atlas Contractus in two volumes with Jansson's other son-in-law Elizée Weyerstraet with the imprint 'Joannis Janssonii haeredes' in 1666. These maps also refer to the firm of Janssonius-Waesbergius. The name of Moses Pitt, an English map publisher, was added to the Janssonius-Waesbergius imprint for maps printed in England for use in Pitt's English Atlas. Learn More...