This item below is out of stock, but another example (left) is available. To view the available item, click "Details."

Details

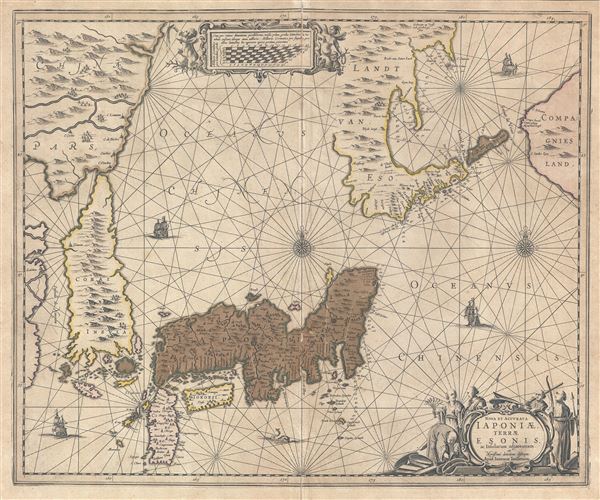

1644 Jansson Map of Japan and Insular Korea

1644 (undated) $1,900.00

1658 Jansson Map of Japan and Insular Korea

JapanKorea-jansson-1690

Title

1658 (undated) 18 x 22 in (45.72 x 55.88 cm) 1 : 4510000

Description

We will begin with the first, the inclusions of Maerten de Vries and Cornelis Jansz Coen's cartography, since it so heavily impacts all other aspects of this map. A 16th century Spanish legend of uncertain origins described gold and silver rich islands located somewhere to the east of Japan. These islands were so saturated in precious metals that the tall, friendly, light skinned inhabitants even fashioned their homes out of gold. As improbable as it may seem, the idea inspired at least two expeditions to the region. Anthony Van Diemen, the director of the Dutch East India Company in the Indies, initiated an unsuccessful first expedition under Abel Jansz Tasman and Matthijs Hendricksz Quast in 1639, and a second more interesting expedition under Maerten de Vries and Cornelis Jansz Coen in 1643. It is this latter mission that most influenced the present map.

Starting at soundings originating due south of Yokohama Bay, we can follow the expedition as it traveled north passing a newly mapped archipelago, then proceeding along the coast of Japan before heading northwest to the coast of Hokkaido, here identified as Eso. The expedition then followed the southeast coast of Hokkaido in a northeasterly direction where it encountered at least two of the Kuril Islands, Kunashir and Iturop, before sailing westward where the navigators correctly identified the forklike peninsulas of southern Sakhalin, but not the strait that separated them from Hokkaido. From here they again sailed south into more known waters.

The achievements and failures of the mission are presented here in full glory. Vries and Coen were the first Europeans to enter these waters, which were in fact little known even to the Japanese. They made early contact with the indigenous Ainu people of Hokkaido, who they noted had silver-hilted daggers. They were the first to discover the Kuril Islands, here identified as Staten Eylant, which is a reasonable approximation of Kunashir, and Compagniesland, a grossly oversize misrepresentation of Iturop. Between Staten Eylant and Compagniesland, they mapped the Straat de Vries. They believed this strait to separate Asia from America, which Compagniesland formed part of, thus elucidating its magnificent proportions. They were also the first European navigators to discover Sakhalin and map its southern coastline. Apparently the Castricum was mired in a heavy fog as it attempted to explore these seas and thus Vries and Coen failed to notice the strait separating Eso (Hokkaido) from Sakhalin, initiating a cartographic error that would persist well into the 18th century. Despite their many successes, the expedition ultimately failed to discover islands of silver and gold, thus proving definitively to Van Diemen that indeed, no such lands ever existed.

The mapping of Japan's southern islands is primary developed from earlier maps in the 1595 Teixeria / Ortelius model and bears little attention. However, other elements are exceptionally interesting. One of these is the presentation of Korea in insular form. The convention of mapping of Korea as an Island has somewhat mysterious origins but can doubtless be traced to the 1595 Japoniae Insulae Descriptio, drawn by the Portuguese Jesuit Luis Teixeria and published by Ortelius. The model, which presented Korea as a long narrow triangular island with a pointy southern tip, remained relatively consistent until about 1647 or 1648, when cartographers inverted the from presenting the Island of Korea, as seen here, with a wide base and narrow northern terminus. Around this time more sophisticated maps of the region began to be published that exhibited true knowledge of southern Korea - among them the present example. The Island of Jeju, here identified as the I. de Ladrones (Island of Thieves), so named because it was a hotbed of piracy, is clearly identifiable not only in location, as in earlier maps, but also in form. Even so, relatively little was known of the region, especially the Korean mainland, and the first accurate description of Korea would not appear until 1666, when Hendrick Hamel's narrative was published in the Netherlands. Thus insular Korea, as presented here, with a wide southern shore and a narrow northern terminus, enjoyed an ephemeral period of popularity - the present example being among the largest and most elegant representation of that period.

The first state of this map, the present example, was published by Johannes Janssonius in 1658. It appeared in various editions of Janssonius' Nieuwen Atlas, as well as works by other authors, well into the early 1700s. Around 1700 a second state, identifiable by it updated imprint, was issued by Schenk and Valk, who most likely acquired Janssonius' plates for this map at auction in 1695.

Cartographer

Jan Jansson or Johannes Janssonius (1588 - 1664) was born in Arnhem, Holland. He was the son of a printer and bookseller and in 1612 married into the cartographically prominent Hondius family. Following his marriage he moved to Amsterdam where he worked as a book publisher. It was not until 1616 that Jansson produced his first maps, most of which were heavily influenced by Blaeu. In the mid 1630s Jansson partnered with his brother-in-law, Henricus Hondius, to produce his important work, the eleven volume Atlas Major. About this time, Jansson's name also begins to appear on Hondius reissues of notable Mercator/Hondius atlases. Jansson's last major work was his issue of the 1646 full edition of Jansson's English Country Maps. Following Jansson's death in 1664 the company was taken over by Jansson's brother-in-law Johannes Waesberger. Waesberger adopted the name of Jansonius and published a new Atlas Contractus in two volumes with Jansson's other son-in-law Elizée Weyerstraet with the imprint 'Joannis Janssonii haeredes' in 1666. These maps also refer to the firm of Janssonius-Waesbergius. The name of Moses Pitt, an English map publisher, was added to the Janssonius-Waesbergius imprint for maps printed in England for use in Pitt's English Atlas. More by this mapmaker...