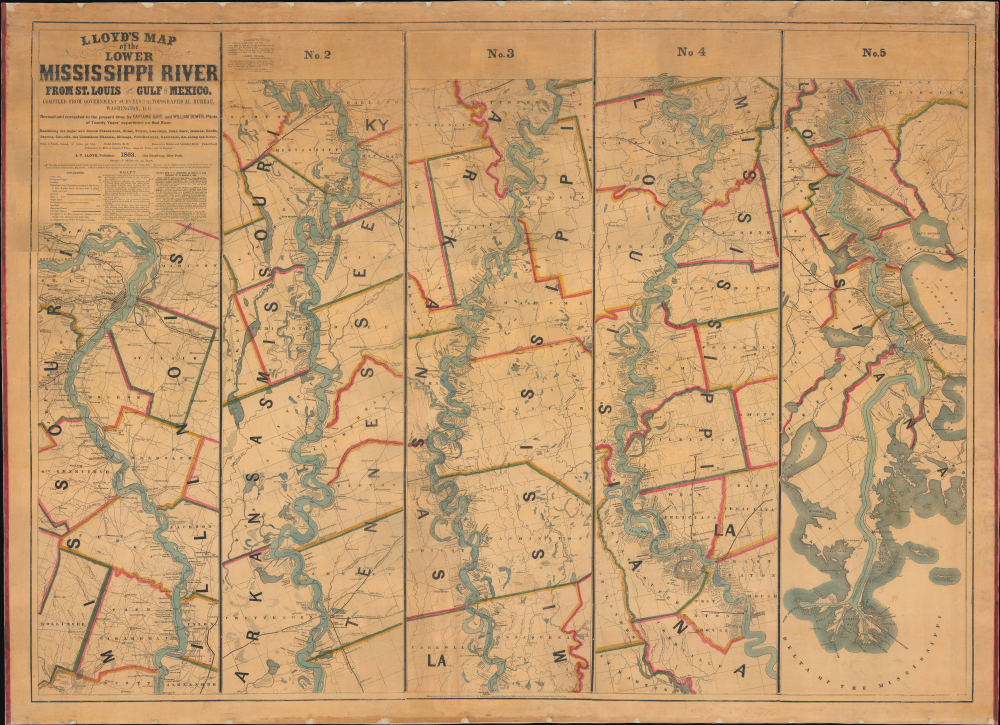

1863 Lloyd Wall Map of the Lower Mississippi River, U.S. Civil War

LowerMississippiRiver-lloyd-1863

Title

1863 (dated) 37.25 x 51.5 in (94.615 x 130.81 cm) 1 : 316800

Description

A Closer Look

The map, a compilation of five 'strip' maps, covers the river from just above St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico. It notes cities, towns, landmarks, plantations, mills, and even individual properties with their owners, effectively serving as a plat map in many places. Roads, railways, islands, shoals, ferry landings and crossings, lighthouses, tributary waterways, canals, lakes, springs, swamps, and other features are recorded throughout. Many features are given colorful names and descriptions, surely derived from the pilots themselves, such as 'Devil's Elbow' and 'Turkey Island.'The best course(s) for ships to take through the river, the culmination of knowledge of thousands of journeys by pilots and other boatmen, is traced in black. Numbers along the route count the distance from New Orleans. Historical events relevant to the history of navigation along the river, such as crashes and particularly fast runs, are also referenced.

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain, 1835 - 1910) is believed to have consulted an example of this map when writing The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. William Bowen, one of the pilots who revised and corrected the map, was a childhood friend and fellow riverboat pilot of Clemens, whom he affectionately called 'my first and oldest and dearest friend.'

The Mighty Mississippi and the U.S. Civil War

Allusions to the war are interspersed along the river, particularly in Tennessee and northern Mississippi, where important battles took place in 1862 and 1863. One of the earliest major Union victories of the war came at the Battle of Island Number Ten (at the top of Map No. 2 here) in March and early April 1862. The Confederates had fortified one of the many prominent bends in the river near New Madrid, Missouri, where the borders of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri meet. The strategic bend was a choke point that might allow Confederate forces to frustrate the Union's 'Anaconda' strategy - if it could be held. Nonetheless, the Union easily took the towns on the Missouri side of the river, including New Madrid, with Confederate troops retreating to Island Number Ten. Union engineers then dug a canal northeast of New Madrid to bypass the island. Though it was too shallow for ironclad gunboats, it proved useful for troop transports and supply ships. In a daring move, two gunboats made successful nighttime runs past the Confederate positions (presaging those that would be used to similar effect at Vicksburg the following year), allowing the Union to have gunboats both up and downriver of Confederate positions, subjecting them to a withering bombardment. Union troops were also positioned to cut off southward retreat, thus forcing some 7,000 Confederates to surrender. The island for which the battle is named no longer exists, having eroded in the years since.The spring of 1862 also saw the Union capture New Orleans, following Farragut's stunning run of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, and the lowest reaches of the Mississippi River, including Baton Rouge. The Confederates' hold of the Mississippi River was suddenly precarious, but they hoped to stunt the Union effort to control the river along other bends and chokepoints. In particular, Vicksburg (near the top of Map No. 4) in northern Mississippi became a focal point. Situated high on a ridge overlooking a bend in the river, it was the best natural defensive position remaining in Confederate hands and was quickly transformed into a 'Gibraltar on the Mississippi.' Both sides understood that the city would become the crux of the entire war in the West, and the Confederates rushed in precious soldiers, supplies, and munitions to defend it.

In May-July 1862, Farragut attempted another daring run past Vicksburg but was stymied, leading him to determine that a purely naval assault on the stronghold was impractical. Instead, the Union persued a grinding advance overland to set the stage for a combined land and sea assault on the stronghold. The plan was for a combined attack, with General Ulysses S. Grant moving southwards from Memphis and General Nathaniel Banks moving north from Baton Rouge. But Banks, a prominent 'political general,' was particularly ineffective and ultimately had little impact on the battle for Vicksburg. Instead, Grant divided his forces in two, one flank under his command and the other under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman. Although Grant's troops were slowed by Confederate harassment, Sherman approached Vicksburg in late December 1862 but was unable to make much headway in a frontal assault, suffering heavy casualties. With winter setting in and with flooding making land operations nearly impossible, the Union side then fell into political infighting and a period of waiting and planning.

After stamping out the infighting, Grant undertook a series of 'bayou operations,' engineering projects to cut channels or capture existing ones that could be used to bypass Vicksburg, leaving the Confederate defenders potentially surrounded or at least unsure from which direction an assault would come. However, these ultimately failed to fundamentally change the situation. By mid-April, action recommenced, with Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter successfully running several boats past Vicksburg on two occasions. Grant then undertook two diversionary attacks to put his troops in an advantageous position for the final assault. Having successfully deceived his opponents, Grant landed his main force at Bruinsburg, near Port Gibson, 30 miles from Vicksburg, without opposition. Taking a circuitous route to further confuse the enemy, his forces captured the state capital of Jackson and then pivoted to the true focus of the campaign, besieging Vicksburg from the east on May 18. Two attempts by Grant to quickly seize the city failed, and both sides settled in for a long siege.

Vicksburg was surrounded by Union forces on land and in the river, cut off from reinforcement or resupply and subject to withering bombardment. Confederate attempts to relieve the siege failed, and Union attempts to use sappers to blow holes in the Confederate defenses did not lead to a breakthrough. By early July, with his army and the city's civilian population on the brink of starvation, the Confederate commander John C. Pemberton (1814 - 1881) began floating terms of surrender. An agreement was reached and enacted on July 4, whereby most Confederate troops would surrender and then be paroled, with some returning to action within a few months. However, others were so disgusted with the war that they shirked military service and returned home, disillusioned with the Rebel cause, as Grant anticipated. Along with the Union victory at Gettysburg just a day earlier, the capture of Vicksburg is often seen as the main turning point of the U.S. Civil War. With some ancillary operations in the following days, the capture of Vicksburg gave the Union total control of the Mississippi River, fulfilling the early war plan to cut the Confederacy in half.

The 'Anaconda Plan'

The 'Anaconda Plan' was a strategy developed in the opening days of the conflict by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott (1786 - 1866). Although Scott had retired by the end of 1861, the plan remained an overall guiding principle for the Union in the following months and years and is generally considered a critical component in the Union's ultimate victory. The basic conception of the plan was straightforward; Scott, recognizing the North's very considerable advantage in naval capabilities, planned to have the Union blockade Southern ports and then gain control of the Mississippi River, cutting the Confederacy in two and choking off one of its main conduits of internal trade and transport. (The other was the underdeveloped railroad network that was overburdened by the demands of the war.) Union forces could then utilize the river to attack the Confederate heartland at multiple points.In some respects, this plan was not very effective, as smugglers, more often than not, could run the Union blockade of Southern ports. However, the thinking behind the plan was a major motivation for Union offensives in the Western Theater, whereby Union troops gradually moved southwards along the river, capturing forts and strategic points, culminating in the capture of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. As Scott had hoped, Union control of the Mississippi River posed an overwhelming problem for the Confederacy, especially as the Southern armies in the Western Theater were badly degraded by the fighting up to and including Vicksburg. The western part of the Confederacy, including Texas, which was a significant source of supplies, was effectively isolated from the heart of the Confederacy. This separation helped Grant's armies, at least the better-led ones, run roughshod through the South, evidenced most clearly the following year (1864) in Sherman's capture of Atlanta and the 'March to the Sea.'

Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by James T. Lloyd, not to be confused with H. H. Lloyd, whom the former disparages in an aside below the title here. The first edition was copyrighted in 1862, while this second edition, adding the information about operations during the war, was copyrighted in 1863 and believed to have been published in 1864. (In any event, it could not have appeared earlier than the second half of 1863, after the capture of Vicksburg.) As explained below the title here, the map was issued in several formats, including separate 'strip maps' that were joined on a single sheet, a pocket map, and a wall map on rollers, as was originally the case with this example.This map is both rare and highly desirable. Catalog listings are somewhat confused due to the two editions and uncertainty over the actual versus the stated publication date of the second edition. A digitized example held by the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection has also been populated in many catalogs, making the map appear more widely distributed in the OCLC than it actually is. Aside from the Rumsey Collection, physical examples of the present 1863 edition are cataloged at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, Washington University in St. Louis, the Wisconsin Historical Society, Pennsylvania State University, the New York Public Library, and the Library of Congress.

Cartographer

James T. Lloyd (fl. c. 1852 - 1865), publishing as J.T. Lloyd, was a New York City based map publisher active in the middle of the 19th century. J. T. Lloyd should not be confused with the competing New York map publisher, H. H. Lloyd, with whom he was often in conflict. Lloyd's maps, despite being printed in New York, frequently focused on the southern states, then in the midst of the American Civil War, likely because before the war Lloyd published steamboat directories of the Mississippi River. Lloyd's maps are noteworthy for their stupendous size and extensive detail as much as for their bombastic advertisements and self-promotion, with which he decorates both the rectos and versos. Surprisingly, given his propensity for self-aggrandizement, very little is known of Lloyd or his life. More by this mapmaker...