This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

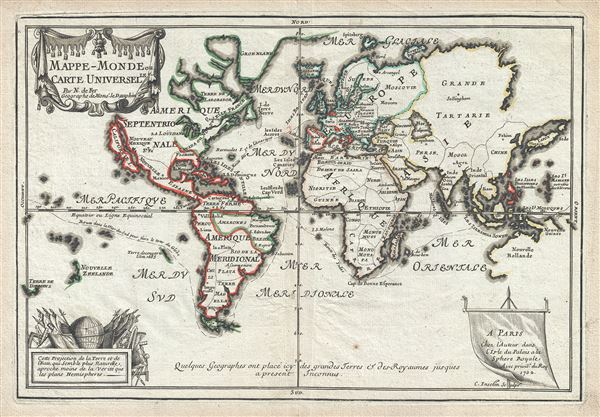

1702 De Fer Map of the World

MappeMondeouCarte-defer-1702

Title

1702 (dated) 9.5 x 13.5 in (24.13 x 34.29 cm) 1 : 112000000

Description

California as an Island or Insular California

Our survey of this map will begin in North America where California is depicted as an island. The idea of an insular California first appeared as a work of fiction in Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo's c. 1510 romance Sergas de Esplandian, where he writesKnow, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.Baja California was subsequently discovered in 1533 by Fortun Ximenez, who had been sent to the area by Hernan Cortes. When Cortez himself traveled to Baja, he must have had Montalvo's novel in mind, for he immediately claimed the Island of California for the King. By the late 16th and early 17th century ample evidence had been amassed, by explorations of the region by Francisco de Ulloa, Hernando de Alarcon and others, that California was in fact a Peninsula and not and island. However, by this time other factors were in play. Francis Drake had sailed north and claimed 'New Albion' near modern-day Washington or Vancouver for England. The Spanish thus needed to promote Cortes' claim on the 'Island of California' to preempt English claims on the western coast of North America. The significant influence of the Spanish crown on European cartographers caused a major resurgence of the Insular California theory. Shortly after this map was made, Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit missionary, traveled overland from Mexico to California, proving conclusively the peninsularity of California.

To the north, De Fer hides the northwest coast of North America, leaving open the hope of a Northwest Passage. Further south, the cartography of South America is nearly as confused as that of North America. Though, by this point in history, the general outlines of South America are well established by regular circumnavigations of the continent, the interior is entirely speculative. An unknown landmass appears just south of Tierra del Fuego, which is quite possibly the tip of the speculative southern continent or 'Terre Australe'

Crossing the Atlantic we find ourselves on the great continent of Africa. Like South America, Africa is well mapped along its shores but speculative in the interior. Several African kingdoms are noted, including the Kingdom of Monomotapa. This region of Africa held a particular fascination for Europeans since the Portuguese first encountered it in the 16th century. At the time, this area was a vast empire called Mutapa or Monomotapa that maintained an active trading network with faraway partners in India and Asia. As the Portuguese presence in the area increased in the 17th century, the Europeans began to note that Monomotapa was particularly rich in gold. They were also impressed with the numerous well-crafted stone structures, including the mysterious nearby ruins of Great Zimbabwe. This combination led many Europeans to believe that King Solomon's Mines, a sort of African El Dorado, must be hidden in this region. Monomotapa did in fact have rich gold mines in the 16th and 17th centuries, but most have these had been exhausted by the 1700s.

Moving into Asia, De Fer offers us a fairly accurate mapping of Asia Minor, Persia and Arabia. The Caspian Sea is corrected to a north-south axis though remains a bit lumpy in form. The Korean Peninsula is rendered unnaturally narrow. Northeastern Asia is curiously mapped, speculating a possible connection to North America.

Next we turn our attention to the Austral Seas. Australia itself appears as Nouvelle Hollande and is connected to the island of New Guinea. Much of its western and northern shores have been mapped, but the eastern shores remain unexplored and the interior is entirely unknown. Tasmania, labeled 'Terre de Diemens', on the opposite side of the map, appears in an embryonic form with only its southern shores noted. A little further east we encounter an extremely embryonic New Zealand. There is no trace of the two island layout or, for that matter, an eastern shoreline.

No Terree Australe?

Though this map offers much, it is also notable for what it does not include. De Fer makes a bold and prescient statement in choosing not to map the speculative southern continent of Terre Australe. Long before the discovery of Antarctica, the southern continent, supposedly capping the South Pole, was speculated upon by European geographers of the 16th and 17th centuries. It was thought, according to Platonic theory, that the globe was a place of balances and thus geographers presumed the bulk of Eurasia must be counterbalanced by a similar landmass in the Southern Hemisphere, just as, they argued, the Americas counterbalanced Africa and Europe. Many explorers in the 16th and 17th centuries sought the Great Southern continent, including Quiros, Drake, and Cook, but Antarctica itself was not truly discovered until Edward Bransfield and William Smith sighted the Antarctic Peninsula in 1820. In choosing not to include Terre Australe, De Fer is breaking with a long-standing cartographic convention common both before and after this publication of his map. He does however include a note at the bottom of the map which roughly translates into 'Geographers have up to the present known of some icy and large lands and kingdoms'.All in all, a magnificent and fascinating map of the world. This map was engraved by Charles Inselin and created by Nicholas De Fer for his 1701 Atlas.

CartographerS

Nicholas de Fer (1646 - October 25, 1720) was a French cartographer and publisher, the son of cartographer Antoine de Fer. He apprenticed with the Paris engraver Louis Spirinx, producing his first map, of the Canal du Midi, at 23. When his father died in June of 1673 he took over the family engraving business and established himself on Quai de L'Horloge, Paris, as an engraver, cartographer, and map publisher. De Fer was a prolific cartographer with over 600 maps and atlases to his credit. De Fer's work, though replete with geographical errors, earned a large following because of its considerable decorative appeal. In the late 17th century, De Fer's fame culminated in his appointment as Geographe de le Dauphin, a position that offered him unprecedented access to the most up to date cartographic information. This was a partner position to another simultaneously held by the more scientific geographer Guillaume De L'Isle, Premier Geograph de Roi. Despite very different cartographic approaches, De L'Isle and De Fer seem to have stepped carefully around one another and were rarely publicly at odds. Upon his death of old age in 1720, Nicolas was succeeded by two of his sons-in-law, who also happened to be brothers, Guillaume Danet (who had married his daughter Marguerite-Geneviève De Fer), and Jacques-François Bénard (Besnard) Danet (husband of Marie-Anne De Fer), and their heirs, who continued to publish under the De Fer imprint until about 1760. It is of note that part of the De Fer legacy also passed to the engraver Remi Rircher, who married De Fer's third daughter, but Richer had little interest in the business and sold his share to the Danet brothers in 1721. More by this mapmaker...

Charles Inselin (fl. c. 1700 - 1730) was a prominent French engraver active in Paris during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Inselin engraved for prominent cartographers ranging from Nicholas Sanson to Eusebio Kino and Nicholas De Fer. He was also a minor publisher of maps and engravings on his own account. Little else is known of his life. Learn More...