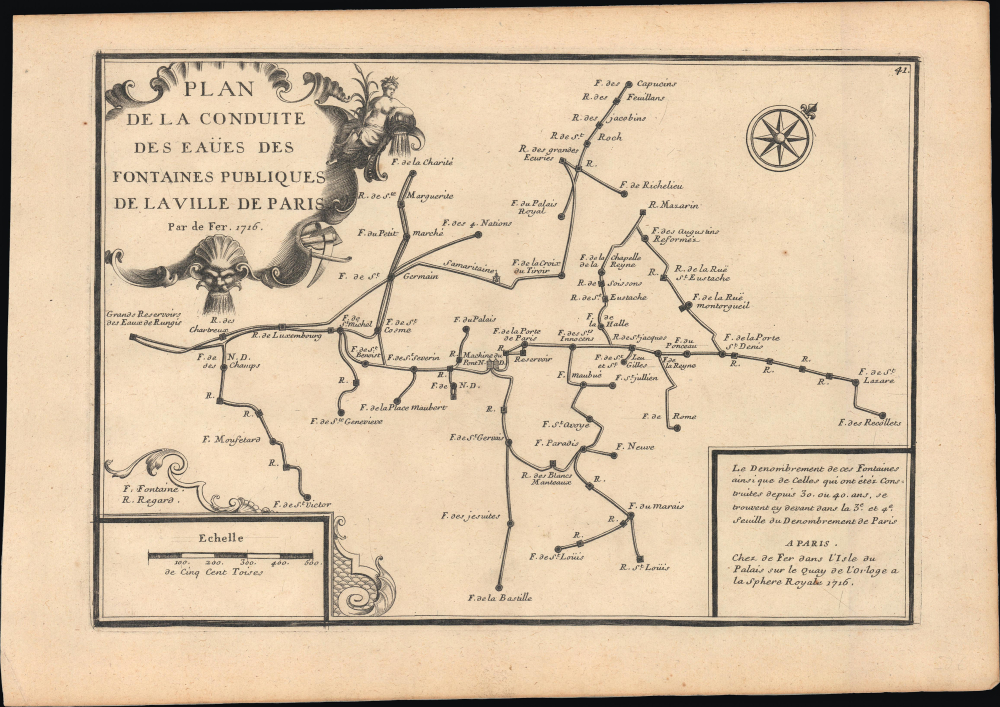

1716 De Fer Map of Paris and Environs, Water Supply

ParisFountains-defer-1716

Title

1716 (dated) 9 x 12.75 in (22.86 x 32.385 cm) 1 : 150000

Description

A Closer Look

Oriented towards the northeast, this map covers what is now the central section of Paris, roughly from the Place Vendôme at top to the Place de la Bastille at bottom, and the area around the Jardin du Luxembourg at left to the area that today is just south of Gare de l'Est in the 10th Arrondissement at right. Abbreviations are explained above the scale at bottom-left; 'R.' here is not an abbreviation for 'rue' but for 'regard,' meaning 'manhole,' which in this context was a small stone hut that allowed access to the wells, pipes, and aqueducts providing water to the city. Explanatory text at bottom-right refers to other pages in the Atlas Curieux where all the fountains were listed.Historical Context

The context for this map is that Paris had long suffered chronic shortages of water, a problem that was only worsening by the year as the capital's population grew (from 415,000 in 1637 to 600,000 in 1700). Some of the city's water came from springs and wells, but the majority came from the Seine, which was filled with wastewater and other impurities. There was very little understanding of the sources of waterborne disease at the time, and Paris' sewer system was equally inadequate, so that the result was a city rife with disease.Still, even the tainted water supply was insufficient to meet the city's needs. Efforts undertaken in the reign of Henry IV and his successor Louis XIII (discussed below) improved the situation somewhat. Still, it was only in the last days of the Ancien Régime and into the Napoleonic Period that more noticeable improvements came. Only the remaking of Paris by Georges-Eugène Haussmann (and the development of germ theory) in the 1850s and 1860s left Paris with a ready supply of clean water, and good sewers to boot.

The 'Aqueduc Médicis'

The 'Grands reservoirs des eaux de Rungis' referred to at left were connected to the city via the 'Aqueduc Médicis,' named after Marie de Médicis, the wife of Henry IV and queen until his assassination in 1610, and then regent to her young son, Louis XIII (r. 1610 - 1643). Improving Paris' water supply had been a major concern for Henry IV, and during her regency, Mary was determined to complete an aqueduct from Rungis, as discussed by the late king. Louis XIII laid the first stone for the aqueduct in honor of his slain father in 1613, and it was completed and went into service a decade later, in 1623. Mostly built underground, the aqueduct has one large and impressive bridge across the Bièvre Valley. It closely follows the path of a Roman aqueduct built in the 2nd or early 3rd century CE, which was only briefly in use before attacks on the city forced residents of the left (south) bank to flee to the Île de la Cité.Parisian Pumps

'Samaritaine' near the center refers to the Pompe de la Samaritaine, a large water wheel built along the Seine at the Pont Neuf to provide water to the fountains and royal palaces nearby. It was originally completed in 1608 (at the request of Henry IV) and elaborated several times, including a significant upgrade in 1712, becoming a major source of water in the central part of the city. A similar pump was built on the Pont Notre-Dame in 1676 and was likewise an important feature in the city's water system. Both pumps can be seen alongside their respective bridges in the famous, monumental 1739 Turgot map of Paris (also sold by us, Paris-turgot-1739-2).Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by Nicholas de Fer in 1716 for his Atlas Curieux. It also appeared in some printings of his similar, contemporary work Beautés de la France. This map is independently cataloged among the holdings of DePaul University, Leiden University, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and the Universitätsbibliothek Bern, and is also cataloged among the holdings of the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection as part of a complete example of the Atlas Curieux.Cartographer

Nicholas de Fer (1646 - October 25, 1720) was a French cartographer and publisher, the son of cartographer Antoine de Fer. He apprenticed with the Paris engraver Louis Spirinx, producing his first map, of the Canal du Midi, at 23. When his father died in June of 1673 he took over the family engraving business and established himself on Quai de L'Horloge, Paris, as an engraver, cartographer, and map publisher. De Fer was a prolific cartographer with over 600 maps and atlases to his credit. De Fer's work, though replete with geographical errors, earned a large following because of its considerable decorative appeal. In the late 17th century, De Fer's fame culminated in his appointment as Geographe de le Dauphin, a position that offered him unprecedented access to the most up to date cartographic information. This was a partner position to another simultaneously held by the more scientific geographer Guillaume De L'Isle, Premier Geograph de Roi. Despite very different cartographic approaches, De L'Isle and De Fer seem to have stepped carefully around one another and were rarely publicly at odds. Upon his death of old age in 1720, Nicolas was succeeded by two of his sons-in-law, who also happened to be brothers, Guillaume Danet (who had married his daughter Marguerite-Geneviève De Fer), and Jacques-François Bénard (Besnard) Danet (husband of Marie-Anne De Fer), and their heirs, who continued to publish under the De Fer imprint until about 1760. It is of note that part of the De Fer legacy also passed to the engraver Remi Rircher, who married De Fer's third daughter, but Richer had little interest in the business and sold his share to the Danet brothers in 1721. More by this mapmaker...