This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

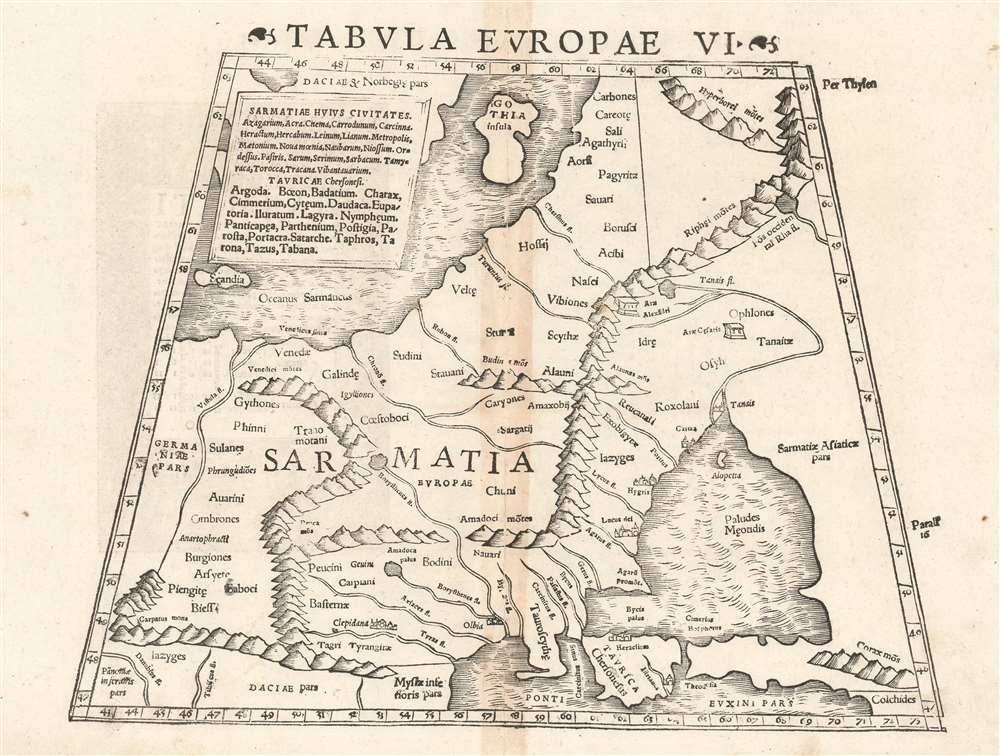

1552 Ptolemaic Map of Eastern Europe as it was Known to Ptolemy

SarmatiaEurope-munster-1552

Title

1552 (undated) 10.25 x 13.25 in (26.035 x 33.655 cm) 1 : 7000000

Description

Publication History and Census

This map appeared in Sebastian Munster's modernized Ptolemy, which was printed in four editions in 1540, 1542, 1545 and 1552. The typography of this example (including the glaring typo in the title) identifies it as belonging to the 1552 edition. Several examples of the separate map appear in OCLC in various editions; the entire book is held by a number of institutions. This is a map that appears on the market from time to time.CartographerS

Sebastian Münster (January 20, 1488 - May 26, 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, Hebrew scholar and humanist. He was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518, after which he was appointed to the University of Basel in 1527. As Professor of Hebrew, he edited the Hebrew Bible, accompanied by a Latin translation. In 1540 he published a Latin edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, which presented the ancient cartographer's 2nd century geographical data supplemented systematically with maps of the modern world. This was followed by what can be considered his principal work, the Cosmographia. First issued in 1544, this was the earliest German description of the modern world. It would become the go-to book for any literate layperson who wished to know about anywhere that was further than a day's journey from home. In preparation for his work on Cosmographia, Münster reached out to humanists around Europe and especially within the Holy Roman Empire, enlisting colleagues to provide him with up-to-date maps and views of their countries and cities, with the result that the book contains a disproportionate number of maps providing the first modern depictions of the areas they depict. Münster, as a religious man, was not producing a travel guide. Just as his work in ancient languages was intended to provide his students with as direct a connection as possible to scriptural revelation, his object in producing Cosmographia was to provide the reader with a description of all of creation: a further means of gaining revelation. The book, unsurprisingly, proved popular and was reissued in numerous editions and languages including Latin, French, Italian, and Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Münster's death of the plague in 1552. Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, passing through 24 editions between 1544 and 1628. This success was due in part to its fascinating woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). Münster's work was highly influential in reviving classical geography in 16th century Europe, and providing the intellectual foundations for the production of later compilations of cartographic work, such as Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Münster's output includes a small format 1536 map of Europe; the 1532 Grynaeus map of the world is also attributed to him. His non-geographical output includes Dictionarium trilingue in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and his 1537 Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Most of Munster's work was published by his stepson, Heinrich Petri (Henricus Petrus), and his son Sebastian Henric Petri. More by this mapmaker...

Claudius Ptolemy (83 - 161 AD) is considered to be the father of cartography. A native of Alexandria living at the height of the Roman Empire, Ptolemy was renowned as a student of Astronomy and Geography. His work as an astronomer, as published in his Almagest, held considerable influence over western thought until Isaac Newton. His cartographic influence remains to this day. Ptolemy was the first to introduce projection techniques and to publish an atlas, the Geographiae. Ptolemy based his geographical and historical information on the "Geographiae" of Strabo, the cartographic materials assembled by Marinus of Tyre, and contemporary accounts provided by the many traders and navigators passing through Alexandria. Ptolemy's Geographiae was a groundbreaking achievement far in advance of any known pre-existent cartography, not for any accuracy in its data, but in his method. His projection of a conic portion of the globe on a grid, and his meticulous tabulation of the known cities and geographical features of his world, allowed scholars for the first time to produce a mathematical model of the world's surface. In this, Ptolemy's work provided the foundation for all mapmaking to follow. His errors in the estimation of the size of the globe (more than twenty percent too small) resulted in Columbus's fateful expedition to India in 1492.

Ptolemy's text was lost to Western Europe in the middle ages, but survived in the Arab world and was passed along to the Greek world. Although the original text almost certainly did not include maps, the instructions contained in the text of Ptolemy's Geographiae allowed the execution of such maps. When vellum and paper books became available, manuscript examples of Ptolemy began to include maps. The earliest known manuscript Geographias survive from the fourteenth century; of Ptolemies that have come down to us today are based upon the manuscript editions produced in the mid 15th century by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus, who provided the basis for all but one of the printed fifteenth century editions of the work. Learn More...