This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

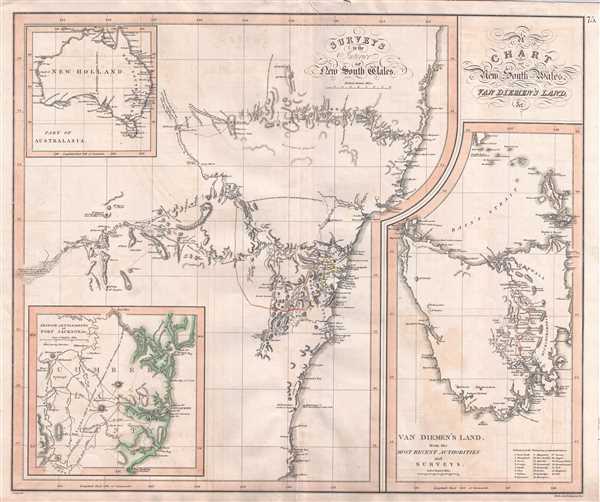

1827 Aspin Map of the Oxley Expedition New South Wales, Australia and Tasmania

NewSouthWalesTasmania-aspinjehoshaphat-1827

Title

1827 (undated) 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 60.96 cm) 1 : 1900000

Description

The primary map details two separate exploratory voyages undertaken by Oxley and Evans. The first, initiated in 1817, was intended to extend the 1815 Evans discoveries the Lachlan Valley. It was assumed that the Lachlan River must be navigable to unknown point on Australia's south coast and thus pass through excellent interior lands ripe for settlement. The Oxley expedition roughly followed Evans to Bathhurst before continuing westward into the Lachlan Valley. Around the modern day town of Forbes, the expedition was impeded by an impenetrable marshland, and instead turned southwest, intending to proceed thus to the coast. After several days they found themselves in a dry desert. Oxley wrote

I am [convinced] that, for all practical purpose of civilized man, the interior of this country, westward of a certain meridian, is uninhabitable; deprived as it is of wood, water, and grass...Once again the expedition changed course, this time heading northward back to the rich lands along the Lachlan River. On 23 June the Lachlan River was reached: 'we suddenly came upon the banks of the river… which we had quitted nearly five weeks before.' After reaching the river, they continued west until Oxley wrote 'with infinite regret and pain I was forced to come to the conclusion, that the interior of this vast country is a marsh and uninhabitable.' Hence they retraced the river a short distance before heading overland where they met the upper waters of the Macquarie River, which they followed back to Bathurst, arriving in August of 1817.

The following year, 1818, Oxley and Evans decided to further explore the upper Macquarie River. This expedition also set out from Bathurst, traveling northward along the Macquarie. He described the lands through which they passed as 'very beautiful country, thinly wooded and apparently safe from the highest floods.' The team followed the river norward until June 3rd, when, having passed between Mount Forester and Mount Harris, they again encountered an impassible marsh. From here they decided to extend their travels eastward overland towards the coast. Along the way they passed numerous rivers into an exceptionally beautiful country. The culmination of this journey was the discovery of Apsley Falls on the 13th of September. Oxley declared the falls, which he called the 'Bathurst Cataract', as 'one of the most magnificent waterfalls we have seen.' The expedition continued westward, following the Hastings River, to the coast, a point they named Port Macquarie, after the governor of New South Sales, Lachlan Macquarie. The modern city of Port Macquarie was founded shortly afterward in 1821 as a penal settlement.

A secondary map focusing on Tasmania or Van Diemen's Land appears in the lower right quadrant. Though the island is largely unexplored at this point, the chart includes a detail of the roadway between Hobart Town and George Town. Tertiary maps illustrate the vicinity of Port Jackson and Sydney, as well as provide a general overview of the Australian continent.

Oxley published the results of these expeditions in 1820 and general interest supported the production of a large map of the discovery in 1822. Our 1827 map follows on the 1822 map, of which, only institutional examples are known. The present map, also very rare, is thus one of the earliest obtainable maps to illustrate the Oxley discoveries. Tooley identifies this map twice, both times associating it with Jehoshaphat Aspin, a mysterious female author and engraver. All examples of the map are numbered '75' and appear to have been separately issued as supplements to later editions of Thomson's New General Atlas. Thomson's imprint appears nowhere on the map, but the overall style of the map is, with the exception of the map's flamboyant title which is more reminiscent of Faden, consistent with Thomson's aesthetic. The map was engraved by Nathaniel Rogers Hewitt, who also produced a number of other maps associated with John Thomson. Some have suggested that this map may date as late as 1829, but based upon Hewitt's address, 'Buckingham Place,' we can assert with certainty that it cannot be later than 1827.

CartographerS

Jehoshaphat Aspin (fl. c. 1805 - c. 1832) was a British author, humorist, historian, and geographer active in the early 19th century. Aspin is a bit of a mystery, but the name believed to be a nom-de-plume for an unknown female author. Aspin produced a number of children's books, geographies, geographical games, and histories. Her primary work Cosmorama focuses on connections between culturally and geographically disparate peoples, for example, comparing Italian and Malay. Cartographically she appears to have worked with John Thompson, Matthew Carey, and C. V. Lavoisne. More by this mapmaker...

John Thomson (1777 - c. 1841) was a Scottish cartographer, publisher, and bookbinder active in Edinburgh during the early part of the 19th century. Thomson apprenticed under Edinburgh bookbinder Robert Alison. After his apprenticeship, he briefly went into business with Abraham Thomson. Later, the two parted ways, John Thomson segueing into maps and Abraham Thomson taking over the bookbinding portion of the business. Thomson is generally one of the leading publishers in the Edinburgh school of cartography, which flourished from roughly 1800 to 1830. Thomson and his contemporaries (Pinkerton and Cary) redefined European cartography by abandoning typical 18th-century decorative elements such as elaborate title cartouches and fantastic beasts in favor of detail and accuracy. Thomson's principle works include Thomson's New General Atlas, published from 1814 to 1821, the New Classical and Historical Atlas of 1829, and his 1830 Atlas of Scotland. The Atlas of Scotland, a work of groundbreaking detail and dedication, would eventually bankrupt the Thomson firm in 1830, at which time their plates were sequestered by the court. The firm partially recovered in the subsequent year, allowing Thomson to reclaim his printing plates in 1831, but filed again for bankruptcy in 1835, at which time most of his printing plates were sold to A. K. Johnston and Company. There is some suggestion that he continued to work as a bookbinder until 1841. Today, Thomson maps are becoming increasingly rare as they are highly admired for their impressive size, vivid hand coloration, and superb detail. Learn More...

Nathaniel Rogers Hewitt (July 19, 1783 - 1841) was a British engraver active in London during the first half of the 19th century. Hewitt was born in London on the 19th of July 1785. His map engraving work appears as early as 1804, although it is most commonly associated with the 1812 - 1817 atlas maps of publisher John Thomson. Hewitt also worked with James Wyld, Samuel William Fores, and other map publishers of the period. In 1824, Hewitt announced plans to independently publish a series of Parish maps by subscription, and a beautifully engraved map of St. Giles in the Fields followed. The map series must not have been able to attract many followers, as Hewitt declared bankruptcy shortly after in 1826. Learn More...