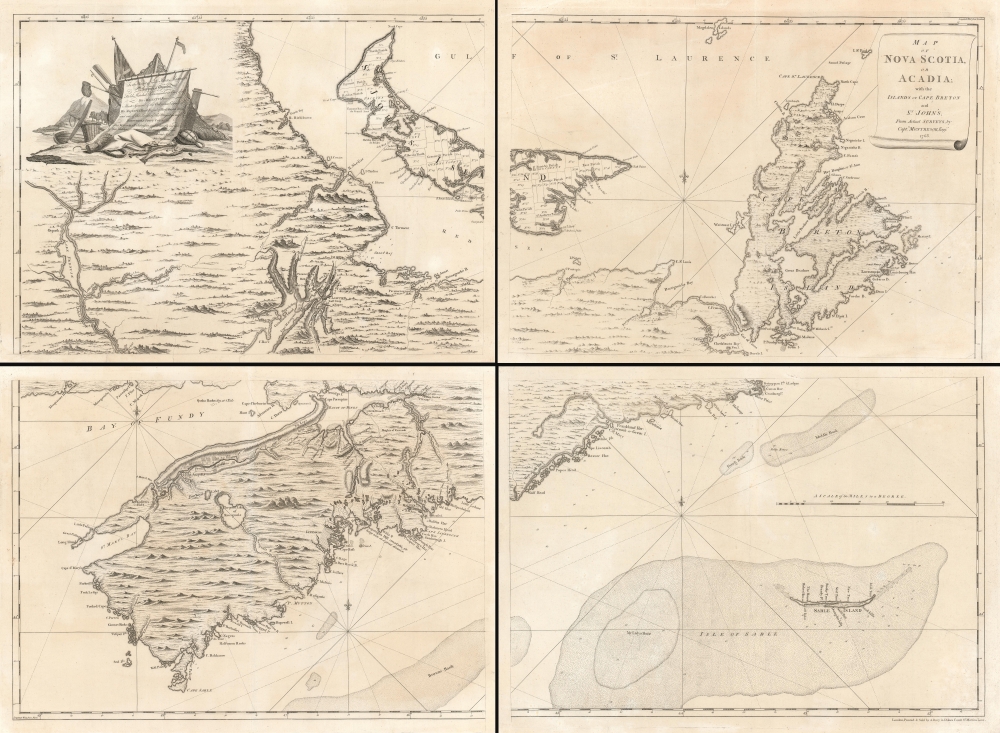

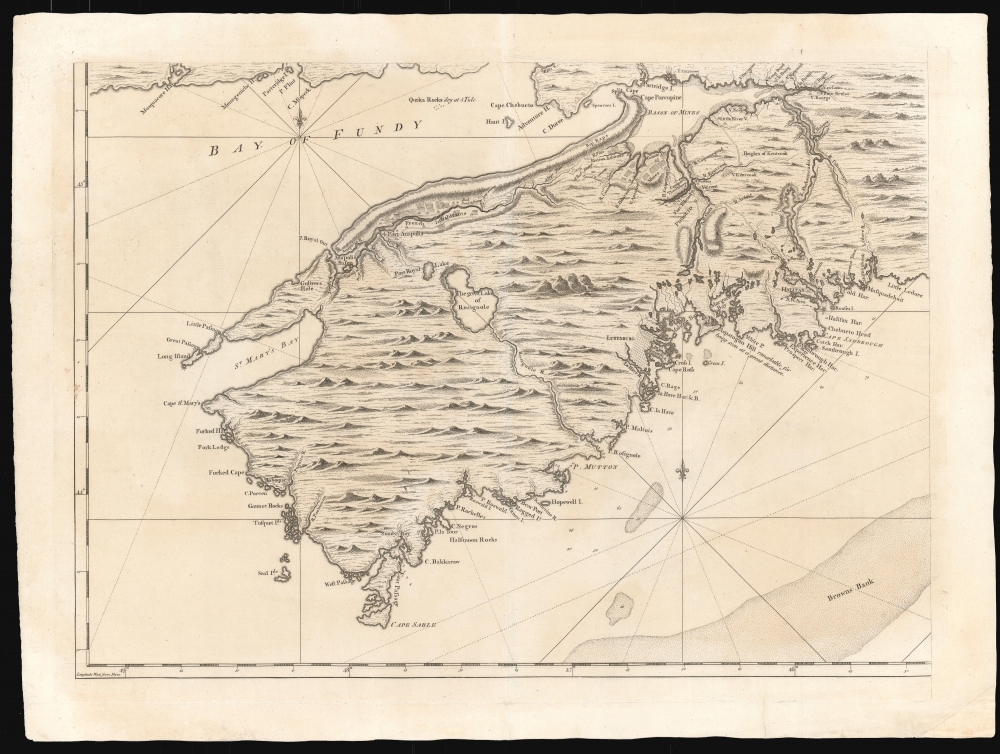

1768 Montresor Map of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island

NovaScotia-montresor-1768

Title

1768 (undated) 39.5 x 55 in (100.33 x 139.7 cm) 1 : 390000

Description

The Scope of the Map

The map illustrates all of Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, and St. John's (now Prince Edward Island.) Part of New Brunswick (up to the Saint John River) is depicted as well. Isle Sable is shown to the southeast.Occupied Nova Scotia

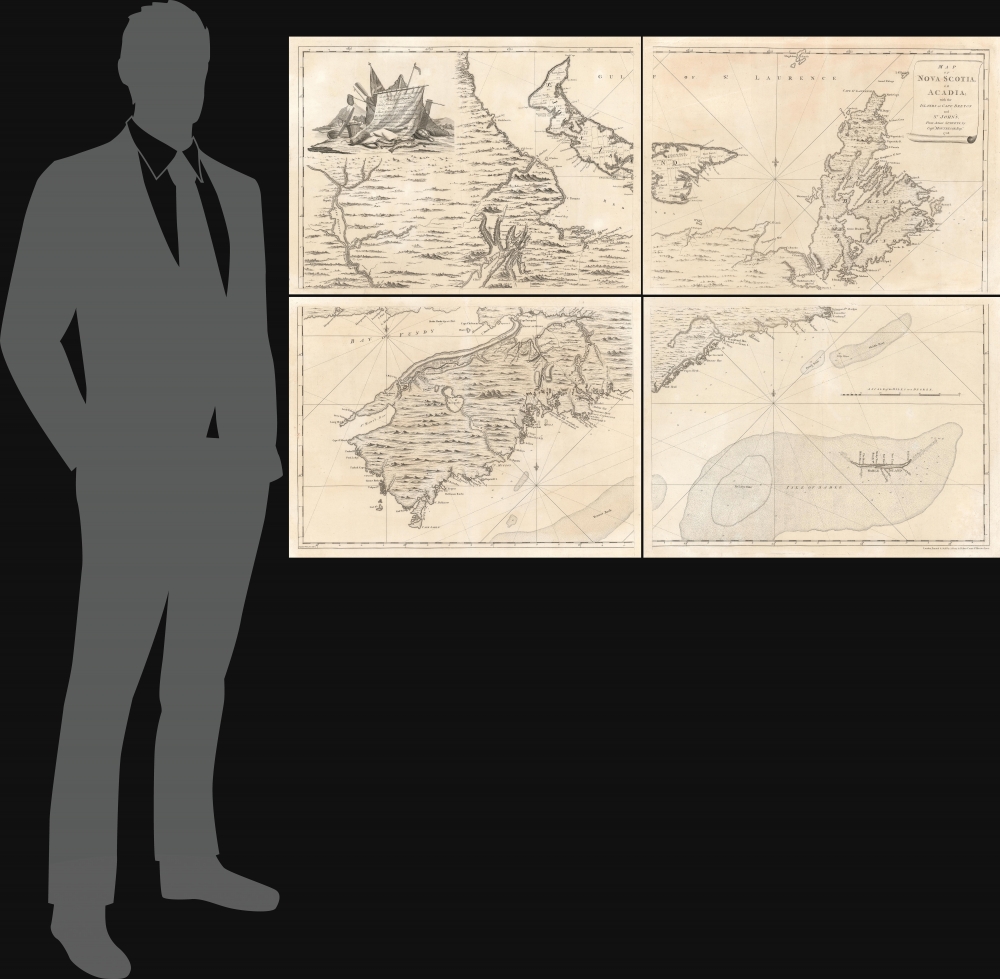

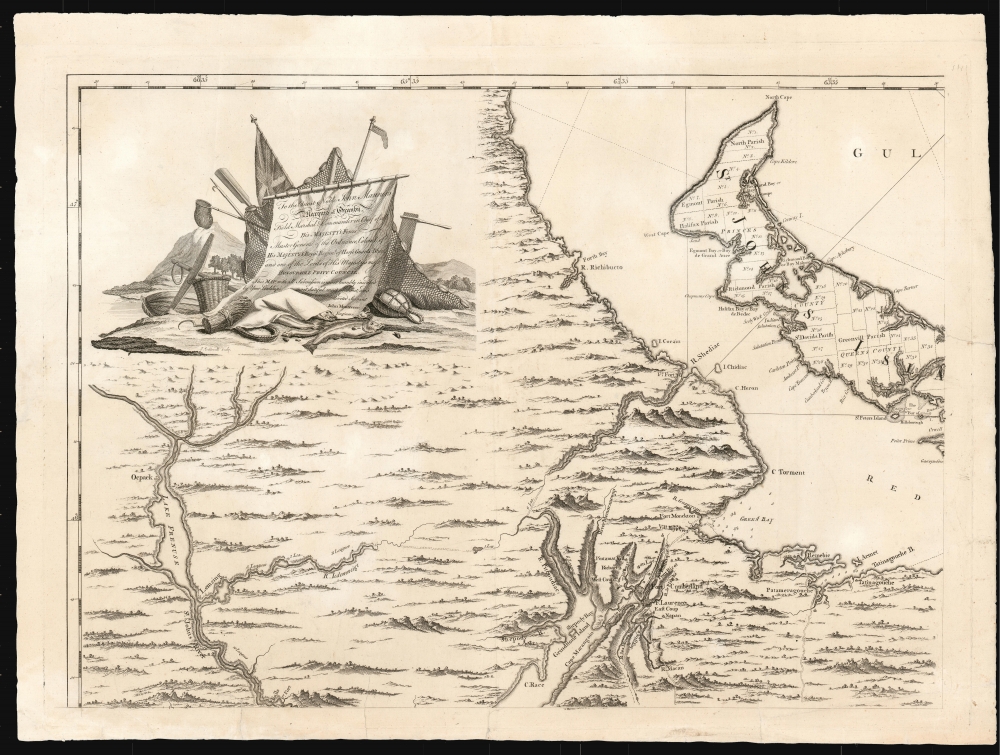

Following the French and Indian War, Nova Scotia and the surrounding islands passed from the French to the British, making it imperative to map the new acquisitions in order to better understand and administer them. The areas mapped here were of particular strategic importance for Britain's efforts to maintain a hold on her American colonies. Halifax had been home to the Royal Navy's North American Station since 1759. But a scientific survey of Nova Scotia, as such, did not occur, at least not in the interior of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, whose attractively engraved hills and vegetation are pictorial, and imaginary. The broad generalities of the map seem to be drawn from the 1755 Jefferys A New Map of Nova Scotia and Cape Britain, or a shared source.My Ladys Hole

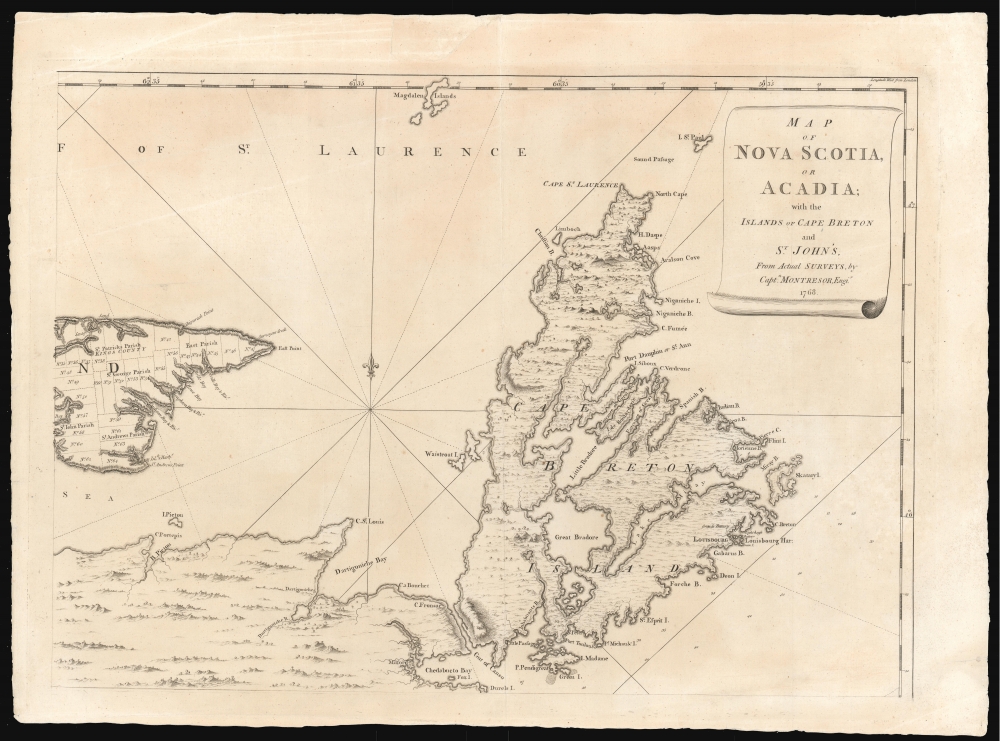

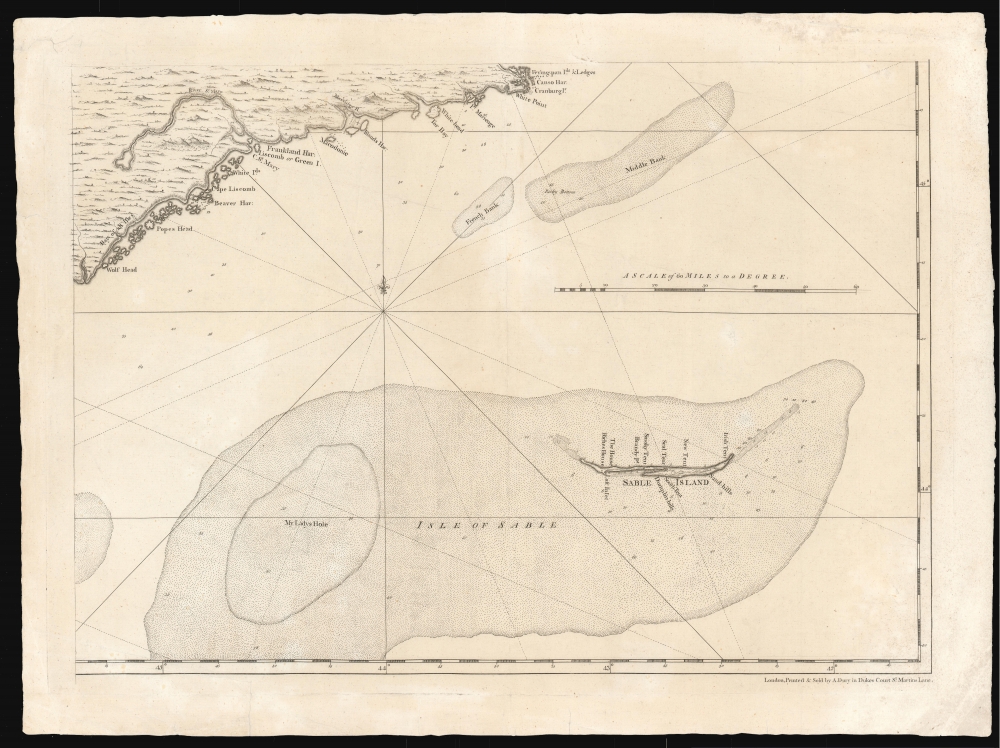

In attempting to determine the sources for a given map, it is often productive to focus on one specific area of it, whose distinctive qualities make it easier to trace from one map to another; the provenance of other, less obvious details then can be more apparent. For example: the southeastern quarter of Montresor's map is dominated by the sand banks and shallows surrounding Sable Island. The banks are shown pictorially, with stippling, and with depth soundings. At the western extreme of the banks, a slightly deeper part of the shallows bears the striking place name 'My Ladys Hole.' No such feature appears on the 1775 DesBarres A Chart of Nova Scotia which is odd: most of DesBarres' charts were based on work overseen by him in Nova Scotia following the French and Indian War. (Indeed, the soundings appearing on the Montresor appear to bear no relation at all to those appearing on the DesBarres.) 'My Ladys Hole' does show itself on the 1755 Jefferys A New Map of Nova Scotia and Cape Britain. The Jefferys, being both a single sheet and showing a broader area than the Montresor, generally lacks the ability to show detail of the four-sheet map. Nevertheless, the Jefferys exhibits more depth soundings than the Montresor - none of which agree between the two maps. The Jefferys does credit his source for this part of his map (a thing Montresor was generally loath to do:) the 1755 map bears the legend here, Nova Scotia fishing banks from Capt. Durel's Chart. This probably refers to Thomas Durell's 1736 A Chart of the Sea Coast of Nova Scotia, Accadia and Cape Breton; we have been able to review a portion of this manuscript, which does appear to inform the Jefferys, but the area pertinent to Isle Sable is not available (the only known example is held in the National Archives, but has not been digitized). No other printed map or chart of these waters that we are aware of features 'My Ladys Hole,' so the candidates are few. We are left with the question: did Montresor draw on Jefferys, or did he draw from the Durell?The difference in scale between the Montresor and the Jefferys necessarily effects the level of detail they present, but it is plain that in terms of interior, topographical detail, the Montresor is little improvement on its predecessor. For example, the stretch of land on Cape Breton Island between St. Peters and Louisbourg contains, on the Jefferys, a string of pictorial, imaginary mountains. The same stretch of land on the Montresor features a more varied, delicately engraved, and equally imaginary topography. The same observation can be applied throughout the map. So when Montresor claimed, as he did in the title of his map, that it was executed from 'Actual Surveys, by Capt. Montresor, Engi.r 1768,' was this an entire fiction, or is there new information added?

Jefferys' depiction of Sable Island is of insufficient scale to include much detail on it, and here Montresor comes out ahead. The shape of the island agrees in large part with the Jefferys, but where the Jefferys adds no place names on the island, Montresor adds specific and ephemeral detail: 'Riches House,' and a number of 'tents' - Smoky Tent, New Tent, Irish Tent, South Tent. Specific houses are noted as well.

The coastlines of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island, as depicted on the Montresor and the Jefferys, are similar enough to preclude any general new survey having taken place. Montresor's mapping of Chedabucto Bay is a marked improvement, showing Milford, and the Milford Haven River in the proper location and form. Cape Breton Island's Great and Little Bras d'Or (Bradore on the map) are much improved. Louisbourg is shown along with its defensive batteries and lighthouse. But in the northwestern portion of Nova Scotia, and the coast of the Bay of Fundy, Montresor's detail and accuracy pass well ahead of the Jefferys - not so much in terms of topography, as the proliferation of specific place names, forts, towns and roads: the sort of details Montresor would have been able to glean in his travels through the region after the Treaty of Paris. The road from Fort Annapolis to Halifax via Grande Pré, in particular, exhibits evidence of firsthand knowledge not evident on the Jefferys, including notations of the quality of the route - 'bad road,' 'a large plain', and 'a bad swamp' confront the traveler en route to the settlements south of the Minas Basin. Grande Pré and its surrounding villages are shown, despite the Acadian population of the area having suffered under the deportations that took place beginning in September 1755, and the burning of the villages beyond Grand-Pré during the war. On the south coast, Lunenburg appears, with a road connecting the settlement with Halifax. The town - founded in 1753 as a part of a British effort to settle Protestants in Nova Scotia displace the Roman Catholic Acadians and indigenous Mi'kmaq - is laid out as a grid, suggestive of available plots for new settlers, primarily land-hungry New Englanders. While Lunenburg is named on the Jefferys, it lacks any level of detail approaching its depiction on the Montresor. On the coast between Lunenburg and Halifax is the key nautical landmark of Aspatogan Hill, 'remarkable for being seen at a great distance.' Unless it comes to light that such details as these were included in Captain Durell's manuscript, it can be said that Montresor contributed original social, political and military detail to the mapping of Nova Scotia, where perhaps he relied on others for the general lay of the land.

Feudal St. John's

To Montresor's 1768 survey has been added Samuel Holland's administrative surveys of St. John's (Prince Edward) Island with the subdivisions of each parish, and many details not present in the first state of the map. Holland's survey of the island went into significantly more depth than did Montresor's, particularly in the vicinity of Charlottetown Bay and New London Bay. The French colony, along with most of New France, was officially ceded to Britain in the 1763 Treaty of Paris. The British sought to develop the island in a feudal system, introducing English and Irish settlers after deporting most of the Acadians (hundreds of whom died en route to France, their transports plagued by sinkings.) The purpose of Holland's survey was to divide the island into the numbered lots visible here. A 1767 lottery awarded these lands to supporters of King George III, who would remain in England. Inevitably, conflict arose between settlers to the island unable to gain land titles, and the absentee landlords who, given the distances involved and their snug connections to the crown, had little incentive to treat fairly with thir remote tenants.Holland's contribution to this map, alas, was not acknowledged by Montresor.

Dedicated to a War Hero

The first, 1768 state of this map bore no dedication. This second state - in addition to Holland's St. John's survey - also includes a dedication to John Manners, the Marquess of Granby and a celebrated, even beloved, British commander. Manners died in 1770, which raises the question of whether the dedication was executed during the man's lifetime, or whether the dedication was posthumous.Publication History and Census

This map was first engraved in 1768, and sold as a separate issue. This example is of the second state, which Kershaw dates to the same year, and which includes Holland's cartography for Prince Edward Island and the Dedication to Granby. Examples of this state were also included in Faden's North American Atlas. Some twenty examples are catalogued separately in OCLC, of indeterminate state and with a date of 1768 universally applied.CartographerS

John Montresor (April 22, 1736 – June 1799) was a British military engineer and cartographer. He was born in Gibraltar to military engineer James Gabriel Montresor. Although educated in England, he learned the rudiments of his future trade from his father, working as his assistant. The two came to America in 1754. The next year the young Montresor served as ensign on the disastrous Braddock expedition, in which the British failed to capture the French Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh) during the French and Indian War (1754 - 1763). Montresor was wounded in the debacle, but nonetheless recede a promotion to Lieutenant. Upon recovering, Montresor went on to serve in northern New York, and accompanied British forces to Halifax. In 1758, commissioned to the Corps of Engineers, he was present at the sieges of Louisbourg and of Quebec (where he drew one of the last known portraits of the doomed General Wolfe.) Following the defeat of the French, the language-handy Montresor was sent as far afield as Cape Breton to elicit oaths of allegiance from Francophone Canadians. During this period, he surveyed and prepared maps of Acadia, the Saint Lawrence River, and of the Kennebec River. He designed and built fortifications in the vicinity of Niagara Falls. As resistance to the Stamp Act built and the Revolution loomed, he surveyed the boundaries between New York and New Jersey. In 1765 in a New York embroiled with Stamp Act riots, Montresor was tasked to draft a plan of the city in order to assist in quelling a full insurrection should it occur. The climate being hostile, Montresor carried out his surveys covertly. The onset of the War found him in Boston; he marched in relief of the British troops who fought at Concord, and took part in the Battles of Long Island and in the 1777 campaigns in New Jersey and Philadelphia, where he launched the attack that destroyed his own Mud Island defenses. Despite his twenty three years of service, he watched as others were repeatedly promoted ahead of him as chief engineer, and he was never promoted beyond Captain. Embittered, he resigned from the military in 1779. More by this mapmaker...

Samuel Holland (1728 - December 28, 1801) was a surveyor and cartographer of extraordinary skill and dedication. Holland was born in the Netherlands in 1728 and, at 17, joined the Dutch Army where he attained the rank of Lieutenant. Around 1754 Holland emigrated to England where he joined the newly forming Royal American Regiment. His skills as a cartographer and surveyor brought him to the attention of his superiors who offered him steady promotions. In 1760 he prepared an important survey of the St. Lawrence River system. It was during this survey that Holland met a young James Cook, who he mentored in the art of surveying. Cook, best known for his exploration of the Pacific, developed many of his own revolutionary nautical surveying techniques based the systems he learnt from Holland. In 1762 Holland caught the attention of the Commission of Trade and Plantations, who governed the British Crown Colonies in America. Under the umbrella of the Trade Commission Holland prepared surveys of the Hudson River Valley and other New York properties. In 1764 he was named Surveyor General for the Northern District, the position in which he did much of his most important work. Holland is also known for surveying done in an attempt to sort out the New York - New Jersey border conflict. Following his work in New York Holland relocated to Canada where, with his new wife of just 21 years, he sired seven children. Like many early surveyors working for colonial governments, Holland was poorly compensated and is known to have supplemented his income by selling the results of his surveys, and those of other surveyors to which he had privileged access, to private publishers, among them the London firm of Laurie and Whittle, who published his work under the pseudonym of 'Captain N. Holland.' Samuel Holland died in Quebec in 1801. Learn More...