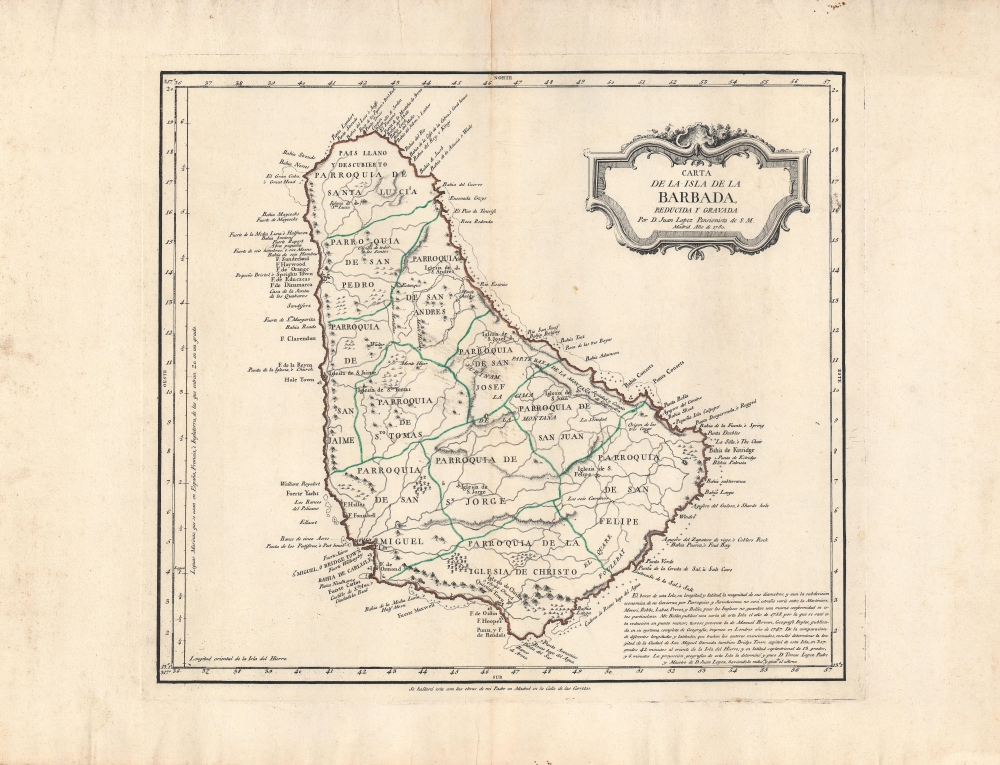

1780 Juan Lopez Map of Barbados

Barbados-lopez-1780

Title

1780 (dated) 13.5 x 15.25 in (34.29 x 38.735 cm) 1 : 109000

Description

A Closer Look

This map shows the island's parishes, towns (including the capital of Bridgetown in the island's southwest), forts, roads, and churches, along with geographical features like mountains, forests, and marshlands. Although soundings are not included, coastal features are noted extensively, including hazards. The left-hand margin includes both latitude and leagues, while the top and bottom margin measure longitude using the Ferro Meridian.One notable feature is the inclusion of many coastal forts (fuerte, mostly abbreviated as 'f.'), reflecting the ongoing contestation of the Caribbean between major European powers, particularly the British, French, and Spanish. This would be especially important for the Spanish king and his ministers (though the hand-colored border, almost certainly added later by someone other than Lopez, obscures the forts' locations somewhat). Although their relations waxed and waned, the British and Spanish were generally at war over the Caribbean for most of the 18th century.

Historical Context

The history of Barbados is in many ways typical of the Caribbean. Disease and slave-raiding drastically reduced the indigenous population soon after contact with Europeans, principally the Spanish. In 1625, the English were the first Europeans to permanently settle Barbados. Soon afterward, sugar cane was introduced from Dutch Brazil, and though Barbados was an English colony, Dutch managers (many of whom were descendants of Sephardic Jews expelled from Iberia) directed the plantation economy. Slave labor was brought from Africa in increasing numbers as the island was converted to a brutal system of sugar production. Absentee landlords in England consolidated lands into a shrinking number of enormous plantations overseen by hired managers.By the mid-17th century, Barbados replaced Hispaniola as the largest sugar-producing colony in the Caribbean and became the most profitable English colony in the Americas by a wide margin. In 1661, the Parliament of Barbados passed the Barbados Slave Code, the first such Slave Act, which became a model throughout the Americas. Though ostensibly meant to prevent especially cruel treatment of slaves, such as wanton killing, the Barbados Slave Code and its imitators codified the status of slaves as chattel property and permitted a range of brutal reprisals for acts of disobedience.

As with the British Empire as a whole, the slave trade was outlawed in Barbados in 1807, but the institution of slavery continued for nearly thirty years afterward. The intervening years were tense and uncertain, as public opinion and the law were moving towards emancipation, but at a snail's pace. In April 1816, a slave rebellion broke out in Barbados, led by an African-born ex-slave named Bussa. The rebels caught wind of debates over abolition in Britain and were distraught at the slow pace of progress. The revolt failed, but, along with uprisings in Guyana and Jamaica, accelerated the pace of abolition in the British Empire. Bussa is honored today as a national hero, and in 1985, a large statue of him was dedicated to Bridgetown. Barbados became independent in 1966 and joined the Commonwealth of Nations. On New Year's Day, 2022, Barbados severed ties with the British monarchy and became a republic, though it remains in the British Commonwealth.

Publication History and Census

This map was made by the cartographer Juan Lopez in conjunction with his father Tomás Lopez, also a cartographer, in 1780. There has been some scholarly debate regarding whether Juan Lopez was actually the son of Tomás Lopez, but the text on this map definitively proves that he was. As noted at bottom-right, this map drew on Emanuel Bowen's 1747 map of Barbados, as well as Jacques Nicholas Bellin's chart of 1758 (https://www.geographicus.com/P/AntiqueMap/Barbados-bellin-1758), among other influences. It most closely resembles Bellin's map but is significantly more elaborated in some respects, especially the naming of bays and other coastal features. This map is quite rare; we note only three institutions that hold it (Harvard University, Michigan University, and the Biblioteca Nacional de España) and it is scarce to the market.CartographerS

Juan Lopez (1765 - 1825) was Spanish cartographer, map publisher, and map dealer active in Spain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Juan Lopez is credited with the first printed edition of Barriero’s highly important 1728 manuscript map, considered the first of Texas by a trained surveyor. Although Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers (K-P, p. 155) asserts that Juan Lopez was not the son of great Spanish cartographer, Tomás Lopez (1730 - 1802), other evidence suggests he most certainly was. There are multiple Lopez catalogs issued in the late 18th century that cite both Juan and Tomás Lopez, including the catalog entry for this very map. He became Geógrafo del Rey to Carlos IV in 1795. Lopez continued producing map to about 1820. More by this mapmaker...

Tomás López de Vargas Machuca (1730 - July 19, 1802) was a Spanish cartographer active in the later part of the 18th century. Vargas was born in Toledo and studied mathematics, grammar, and rhetoric at the Colegio Imperial in Madrid. In 1752, with the patronage of the Marquis de la Ensenada, he relocated to Paris to study. López attended the Mazarin College, where he received two courses in Mathematics and lessons in geography from the Abbé de la Caille, Joseph Jérome de Lalande, and Louis Gabriel. He also studied cartography direclty under the legendary French mapmaker Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1697 - 1782). Back in Madrid, he collaborated with the geographer Juan de la Cruz on two educational atlases, published in 1757 and 1758. Around 1770, King Carolos III, appointed him Geógrafo de los Dominios de Su Magestad and gave him charge over the newly created Gabinete de Geografía. In this position, he dedicated the remainder of his life to a detailed mapping of Spain, producing numerous important regional maps, many correcting common mistakes made by foreign geographers. He also ran a private map publishing business in Madrid, first on San Bernardo (1761 - 65), the on Las Carretas (opposite Gamete; 1765 - 1783), and infamy on Atocha (1783 - 1802). He was a member of the Real Academia de San Fernando, the Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País and the Academia de Bellas Letras de Sevilla. López was succeeded by his two sons, also cartographers, who published several atlases based upon his work. The appraisal of his estate at the time was 489,800 reales (about 1,000,000 USD today), a figure indicative of his success. Learn More...