This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

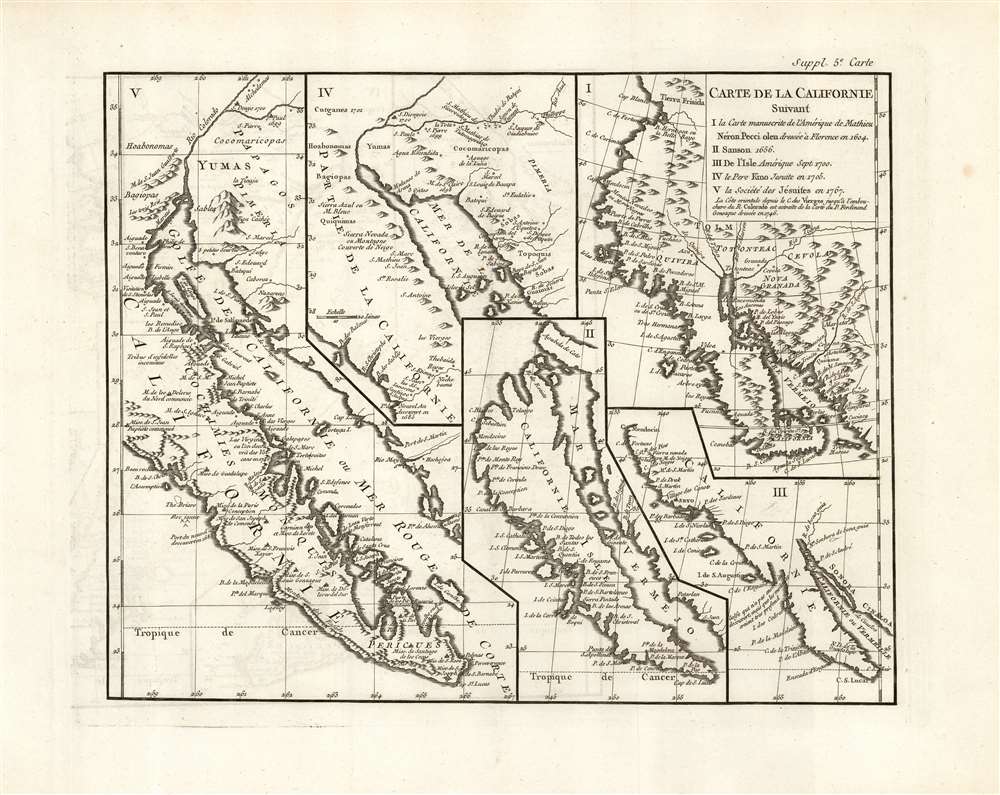

1772 Vaugondy / Diderot Map of California Debunking California as an Island

CarteDeLaCalifornie-vaugondy-1772-2

Title

1772 (undated) 11.5 x 15 in (29.21 x 38.1 cm)

Description

Stages of California Mapping

It opens with the work of Italian cartographer Matheau Neron Pecci (1604) which correctly presumed that the main body of California extended southward into a peninsula. The next map illustrated, by Nicolas Sanson in 1656, was among the most influential of the maps of the 17th century to propose an insular California. Map no. III, by Guillaume Delisle (1700), was one of the first maps produced by a prominent geographer to abandon the insular California. The fourth is the seminal Kino Map. This map, rendered by a Jesuit missionary c.1705, was the work that finally disproved the California as an island theory. Father Franz Kino walked this region between 1698 and 1701. The final map, produced by unnamed Jesuits c. 1767, is a more accurate depiction of the Baja California peninsula. These maps all predate the discoveries of Captain Cook and hence Diderot's work was as much speculative as historical in many respects - although the Jesuit reports pertaining to California’s non-insularity were authoritative.Insular California

The idea of an insular California first appeared as a work of fiction in Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo's c. 1510 romance Las Sergas de Esplandian, where he writesKnow, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.Baja California was subsequently discovered in 1533 by Fortun Ximenez, who had been sent to the area by Hernan Cortez. When Cortez himself traveled to Baja, he must have had Montalvo's novel in mind, for he immediately claimed the 'Island of California' for the Spanish King. By the late 16th and early 17th century ample evidence had been amassed, through explorations of the region by Francisco de Ulloa, Hernando de Alarcon, and others, that California was in fact a peninsula. Nonetheless, by this time other factors were in play. Francis Drake had sailed north and claimed Nova Albion, modern day Washington or Vancouver, for England. The Spanish thus needed to promote Cortez's claim on the 'Island of California' to preempt English claims on the western coast of North America. The significant influence of the Spanish crown on European cartographers spurred a major resurgence of the Insular California theory.

Printed Maps with Insular California

The earliest surviving map to illustrate California as an island is considered to be the 1622 title page to the Michiel Colijn edition of Antonio Herrera's Descriptio Indiae Occidentalis. Even so, the insular California convention formally dates to 1620, when the Dutch seized a Spanish ship transporting the account of Friar Antonio de la Ascension, which was intended for the Council of the Indies. In that work, the good Friar apparently asserted his strong belief that California is insular - although his sources are unknown. While the Friar Antonio account is now lost, a legend on the Henry Briggs map of 1625 conveys this information and that Briggs saw such a map in 1622. Colijn may have seen the same map when preparing this Herrera title page.Publication History and Census

This map is part of the 10 map series prepared by Vaugondy for the Supplement to Diderot's Encyclopédie, of which this is plate 5. The Supplément à l'Encyclopédie is well represented in institutional collections. We see six examples of the separate map catalogued in OCLC.CartographerS

Robert de Vaugondy (fl. c. 1716 - 1786) was French may publishing from run by brothers Gilles (1688 - 1766) and Didier (c. 1723 - 1786) Robert de Vaugondy. They were map publishers, engravers, and cartographers active in Paris during the mid-18th century. The father and son team were the inheritors to the important Nicolas Sanson (1600 - 1667) cartographic firm whose stock supplied much of their initial material. Graduating from Sanson's maps, Gilles, and more particularly Didier, began to produce their own substantial corpus. The Vaugondys were well-respected for the detail and accuracy of their maps, for which they capitalized on the resources of 18th-century Paris to compile the most accurate and fantasy-free maps possible. The Vaugondys compiled each map based on their own geographic knowledge, scholarly research, journals of contemporary explorers and missionaries, and direct astronomical observation. Moreover, unlike many cartographers of this period, they took pains to reference their sources. Nevertheless, even in 18th-century Paris, geographical knowledge was limited - especially regarding those unexplored portions of the world, including the poles, the Pacific Northwest of America, and the interiors of Africa, Australia, and South America. In these areas, the Vaugondys, like their rivals De L'Isle and Buache, must be considered speculative or positivist geographers. Speculative geography was a genre of mapmaking that evolved in Europe, particularly Paris, in the middle to late 18th century. Cartographers in this genre would fill in unknown lands with theories based on their knowledge of cartography, personal geographical theories, and often dubious primary source material gathered by explorers. This approach, which attempted to use the known to validate the unknown, naturally engendered rivalries. Vaugondy's feuds with other cartographers, most specifically Phillipe Buache, resulted in numerous conflicting papers presented before the Academie des Sciences, of which both were members. The era of speculative cartography effectively ended with the late 18th-century explorations of Captain Cook, Jean Francois de Galaup de La Perouse, and George Vancouver. After Didier died, his maps were acquired by Jean-Baptiste Fortin, who in 1787 sold them to Charles-François Delamarche (1740 - 1817). While Delamarche prospered from the Vaugondy maps, he defrauded Vaugondy's window Marie Louise Rosalie Dangy of her rightful inheritance and may even have killed her. More by this mapmaker...

Denis Diderot (October 5, 1713 - July 31, 1784) was a French Enlightenment era philosopher, publisher and writer. Diderot was born in the city of Langres, France and educated at the Lycée Louis le Grand where, in 1732, he earned a master of arts degree in philosophy. Diderot briefly considered careers in the clergy and in law, but in the end chose the more fiscally challenge course of a writer. Though well respected in philosophical circles Diderot was unable to obtain any of the government commissions that commonly supported his set and consequently spent much of his life in deep poverty. He is best known for his role in editing and producing the Encyclopédie . The Encyclopédie was one of the most revolutionary and impressive works of its time. Initially commissioned as a translation of Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, Diderot instead turned into a much larger and entirely new work of monumental depth and scope. Diderot's Encyclopédie was intended to lay bare before the common man the intellectual mysteries of science, art and philosophy. This revolutionary mission was strongly opposed by the powers of the time who considered a learned middle class it a threat to their authority. In the course of the Encyclopédie production Diderot was imprisoned twice and the work itself was officially banned. Nonetheless, publication continued in response to a demand exceeding 4000 subscribers. The Encyclopédie was finally published in 1772 in 27 volumes. Following the publication of the Encyclopédie Diderot grew in fame but not in wealth. When the time came to dower his only surviving daughter, Angelique, Diderot could find no recourse save to sell his treasured library. In a move of largess, Catherine the II Russia sent an emissary to purchased the entire library on the condition that Diderot retain it in his possession and act as her "librarian" until she required it. When Diderot died of gastro-intestinal problems 1784, his heirs promptly sent his vast library to Catherine II who had it deposited at the Russian National Library, where it resides to this day. Learn More...